Related Research Articles

Isaac Rosenberg was an English poet and artist. His Poems from the Trenches are recognized as some of the most outstanding poetry written during the First World War.

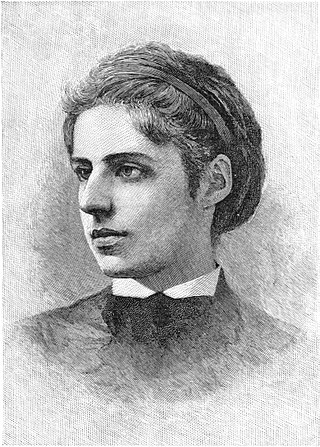

Emma Lazarus was an American author of poetry, prose, and translations, as well as an activist for Jewish and Georgist causes. She is remembered for writing the sonnet "The New Colossus", which was inspired by the Statue of Liberty, in 1883. Its lines appear inscribed on a bronze plaque, installed in 1903, on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty. Lazarus was involved in aiding refugees to New York who had fled antisemitic pogroms in eastern Europe, and she saw a way to express her empathy for these refugees in terms of the statue. The last lines of the sonnet were set to music by Irving Berlin as the song "Give Me Your Tired, Your Poor" for the 1949 musical Miss Liberty, which was based on the sculpting of the Statue of Liberty. The latter part of the sonnet was also set by Lee Hoiby in his song "The Lady of the Harbor" written in 1985 as part of his song cycle "Three Women".

Michael Peter Leopold Hamburger was a noted German-British translator, poet, critic, memoirist and academic. He was known in particular for his translations of Friedrich Hölderlin, Paul Celan, Gottfried Benn and W. G. Sebald from German, and his work in literary criticism. The publisher Paul Hamlyn (1926–2001) was his younger brother.

Edward Kamau Brathwaite, CHB, was a Barbadian poet and academic, widely considered one of the major voices in the Caribbean literary canon. Formerly a professor of Comparative Literature at New York University, Brathwaite was the 2006 International Winner of the Griffin Poetry Prize, for his volume of poetry Born to Slow Horses.

John Rodker was an English writer, modernist poet, and publisher of modernist writers.

Joseph Leftwich, born Joseph Lefkowitz, was a British critic and translator into English of Yiddish literature.

Siegbert Salomon Prawer was Taylor Professor of the German Language and Literature at the University of Oxford.

Moses ben Jacob ibn Ezra, known as Ha-Sallaḥ was an Andalusi Jewish rabbi, philosopher, linguist, and poet. He was born in Granada about 1055–1060, and died after 1138. Ibn Ezra is considered to have had great influence in the Arabic literary world. He is considered one of Spain's greatest poets and was considered ahead of his time in his theories on the nature of poetry. One of the more revolutionary aspects of Ibn Ezra's poetry that has been debated is his definition of poetry as metaphor and how his poetry illuminates Aristotle's early ideas. The importance of ibn Ezra's philosophical works was minor compared to his poetry. They address his concept of the relationship between God and man.

Sir Israel Gollancz, FBA was a scholar of early English literature and of Shakespeare. He was Professor of English Language and Literature at King's College, London, from 1903 to 1930.

Abraham Nahum Stencl was a Polish-born Yiddish poet.

Nathan Alterman was an Israeli poet, playwright, journalist, and translator. Though never holding any elected office, Alterman was highly influential in Socialist Zionist politics, both before and after the establishment of the modern State of Israel in 1948.

Karen Gershon, born Kaethe Loewenthal was a German-born British writer and poet. She escaped to Britain in December 1938.

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature.

East End literature comprises novels, short stories, plays, poetry, films, and non-fictional writings set in the East End of London. Crime, poverty, vice, sexual transgression, drugs, class-conflict and multi-cultural encounters and fantasies involving Jews, Chinamen and Indian immigrants are major themes.

Jacob Glatstein was a Polish-born American poet and literary critic who wrote in the Yiddish language. His name is also spelled Yankev Glatshteyn or Jacob Glatshteyn.

The Whitechapel Boys were a loosely-knit group of Anglo-Jewish writers and artists of the early 20th century. It is named after Whitechapel, which contained one of London's main Jewish settlements and from which many of its members came. These members included Mark Gertler, Isaac Rosenberg, David Bomberg, Joseph Leftwich, Jacob Kramer, Morris Goldstein, Stephen Winsten, John Rodker, Lazarus Aaronson and its only female member, Clara Birnberg.

In 1935, Spanish artist Pablo Picasso, 53, temporarily ceased painting, drawing, and sculpting in order to commit himself to writing poetry, having already been immersed in the literary sphere for years. Although he soon resumed work in his previous fields, Picasso continued in his literary endeavours and wrote hundreds of poems, concluding The Burial of the Count of Orgaz in 1959.

The Young Socialist League was a British radical political youth group founded in 1911. The group was mostly active in London, where it also had the majority of its members. According to the Encyclopedia of British and Irish Political Organizations, the group probably had its roots in the Socialist Sunday Schools. The League was linked to the British Socialist Party, a small Marxist party, also founded in 1911, who were supporters of the Bolshevik Revolution. It published a paper called the Red Flag.

Pauline Ruth "Nina" Salaman was a British Jewish poet, translator, and social activist. Besides her original poetry, she is best known for her English translations of medieval Hebrew verse—especially of the poems of Judah Halevi—which she began publishing at the age of 16.

Emily Marion Harris was an English novelist, poet, and social worker. Many of her writings explored Jewish life in London, and the religious and political conflicts of Jewish traditionalists in the face of increasing assimilation.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Baker, William (May 2015). "Aaronson, Lazarus (1895–1966)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/105000. ISBN 978-0-19-861411-1 . Retrieved 4 June 2015.(subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ↑ Robson, Jeremy (1966). "A Survey of Anglo-Jewish Poetry". Jewish Quarterly . 14 (2): 5–23. doi:10.1080/0449010X.1966.10706502 (inactive 19 September 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of September 2024 (link) - ↑ Dickson, Rachel; MacDougall, Sarah (2004). "The Whitechapel Boys". Jewish Quarterly . 51 (3): 29–34. doi:10.1080/0449010X.2004.10706848 (inactive 19 September 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of September 2024 (link) - ↑ Patterson, Ian (2013). "John Rodker, Julius Ratner and Wyndham Lewis: The Split-Man Writes Back". In Gasiorek, Andrzej; Reeve-Tucker, Alice; Waddell, Nathan (eds.). Wyndham Lewis and the Cultures of Modernity. Ashgate. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-4094-7901-7.

- ↑ Patterson, Ian (2013). "The Translation of Soviet Literature". In Beasley, Rebecca; Bullock, Philip Ross (eds.). Russia in Britain, 1880–1940: From Melodrama to Modernism. Oxford University Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-19-966086-5.

- ↑ Zilboorg, Caroline (2001). The Masks of Mary Renault: A Literary Biography . University of Missouri Press. pp. 67–70, 87. ISBN 978-0-8262-1322-8.

- 1 2 3 Baker, William; Roberts Shumaker, Jeanette (2017). "Pioneers: E. O. Deutsch, B. L. Farjeon, Israel Gollancz, Leonard Merrick, and Lazarus Aaronson". The Literature of the Fox: A Reference and Critical Guide to Jewish Writing in the UK. AMS Studies in Modern Literature. AMS Press. pp. 21–30. ISBN 978-0-404-65531-0.

- 1 2 3 Rubinstein, William D., ed. (2011). "Aaronson, Lazarus Leonard". The Palgrave Dictionary of Anglo-Jewish History. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4039-3910-4.

- ↑ "[In the Divorce Court, London, yesterday...]". The Glasgow Herald . 30 October 1931. p. 11.

- ↑ Trilling, Ossia (28 April 1989). "Lydia Sherwood [obituary]". The Independent . p. 35.

- ↑ Knowlson, James (1993). "Letter: Friends of Beckett". Jewish Quarterly . 40 (1): 72. doi:10.1080/0449010X.1993.10705916 (inactive 19 September 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of September 2024 (link) - ↑ "Portrait Sketch: Laz Aaronson by Graham Hutton". Radio Times . No. 1472. 25 January 1952. p. 16.

- ↑ "No. 41589". The London Gazette (Supplement). 30 December 1958. p. 15.

- ↑ Sutton, David (January 2015). "The Names of Modern British and Irish Literature" (PDF). Name Authority List of the Location Register of English Literary Manuscripts and Letters. University of Reading. p. 1. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- 1 2 Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred, eds. (2007). "Aaronson, Lazarus Leonard". Encyclopaedia Judaica . Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4.

- ↑ Extracts of the reviews are reprinted in Aaronson, L. (1933). Poems. V. Gollancz.

- 1 2 3 Jacobs, Arthur Chaim (1967). "Lazarus Aaronson: Two Unpublished Poems". Jewish Quarterly . 15 (1–2): 13. doi:10.1080/0449010X.1967.10703091 (inactive 19 September 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of September 2024 (link) - ↑ Leftwich, Joseph (1959). "Hasidic Influences in Imaginative English Literature". Jewish Book Annual. 17: 3. Archived from the original on 26 July 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ↑ Baker, William (July 2010). "Reviewed Work: Whitechapel at War: Isaac Rosenberg and his Circle by Sarah MacDougall, Rachel Dickinson". The Modern Language Review . 105 (3): 854. doi:10.1353/mlr.2010.0136. S2CID 246641456.