Pulp magazines were inexpensive fiction magazines that were published from 1896 until around 1955. The term "pulp" derives from the cheap wood pulp paper on which the magazines were printed due to their cheap nature. In contrast, magazines printed on higher-quality paper were called "glossies" or "slicks". The typical pulp magazine had 128 pages; it was 7 inches (18 cm) wide by 10 inches (25 cm) high, and 0.5 inches (1.3 cm) thick, with ragged, untrimmed edges. Pulps were the successors to the penny dreadfuls, dime novels, and short-fiction magazines of the 19th century.

Edward Frederic Benson was an English novelist, biographer, memoirist, historian and short story writer.

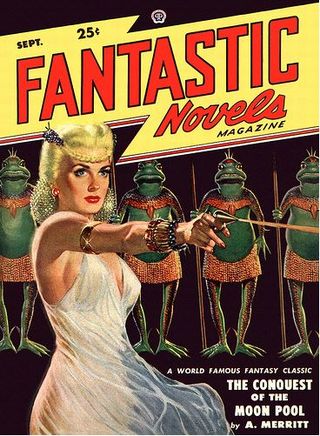

Abraham Grace Merritt – known by his byline, A. Merritt – was an American Sunday magazine editor and a writer of fantastic fiction.

Argosy was an American magazine, founded in 1882 as The Golden Argosy, a children's weekly, edited by Frank Munsey and published by E. G. Rideout. Munsey took over as publisher when Rideout went bankrupt in 1883, and after many struggles made the magazine profitable. He shortened the title to The Argosy in 1888 and targeted an audience of men and boys with adventure stories. In 1894 he switched it to a monthly schedule and in 1896 he eliminated all non-fiction and started using cheap pulp paper, making it the first pulp magazine. Circulation had reached half a million by 1907, and remained strong until the 1930s. The name was changed to Argosy All-Story Weekly in 1920 after the magazine merged with All-Story Weekly, another Munsey pulp, and from 1929 it became just Argosy.

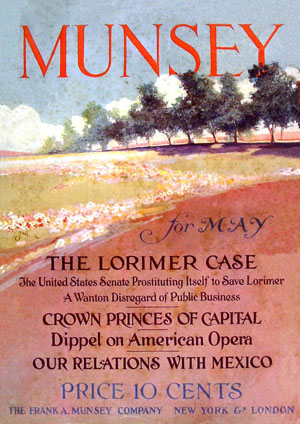

Frank Andrew Munsey was an American newspaper and magazine publisher, banker, political financier and author. He was born in Mercer, Maine, but spent most of his life in New York City. The village of Munsey Park, New York, is named for him, along with The Munsey Building in downtown Baltimore, Maryland, at the southeast corner of North Calvert and East Fayette Streets.

Victor Rousseau Emanuel was a British writer who wrote novels, newspaper series, science fiction and pulp fiction works. He was active in Great Britain and the United States during the first half of the 20th century.

Achmed Abdullah was an American writer apparently from Afghanistan. He gave his full name variously as "Achmed Abdullah Nadir Khan el-Durani el-Iddrissyeh" or as "Alexander Nicholayevitch Romanoff". He is most noted for his pulp stories of crime, mystery and adventure novels. He wrote screenplays for some successful films. He was the author of the progressive Siamese drama Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness, an Academy Award-nominated film made in 1927. He earned an Academy Award nomination for collaborating on the screenplay to the 1935 film The Lives of a Bengal Lancer.

Blue Book was a popular 20th-century American magazine with a lengthy 70-year run under various titles from 1905 to 1975. It was a sibling magazine to The Red Book Magazine and The Green Book Magazine.

Frederick J. Jackson, also known professionally as Fred Jackson and Frederick Jackson and under the pseudonym Victor Thorne, was an American author, playwright, screenwriter, novelist, and producer for both stage and film. A prolific writer of short stories and serialized novels, most of his non-theatre works were published in pulp magazines such as Detective Story Magazine and Argosy. Many of these stories were adapted into films by other writers.

Fantasy Publishing Company, Inc., or FPCI, was an American science fiction and fantasy small press specialty publishing company established in 1946. It was the fourth small press company founded by William L. Crawford.

Henry James O'Brien Bedford-Jones was a Canadian-American historical, adventure fantasy, science fiction, crime and Western writer who became a naturalized United States citizen in 1908.

De Lysle Ferrée Cass (1887–1973) was a writer of fantasy short stories.

Elisabeth Sanxay Holding (1889–1955) was an American novelist and short story writer. She primarily authored fiction in the hardboiled subgenre of detective novels.

Clifford Martin Eddy Jr. was an American writer known for his horror, mystery and supernatural short stories. He is best remembered for his work in Weird Tales magazine and his friendship with H. P. Lovecraft.

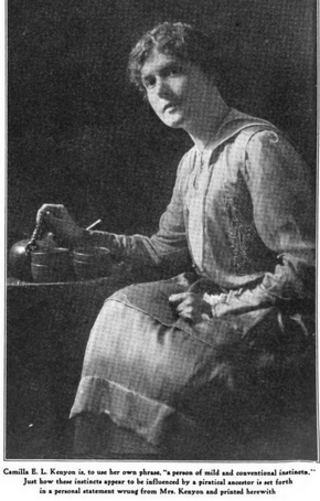

Camilla E. L. Kenyon was an American author of two novels and several short works. Her first novel was Spanish Doubloons, originally published in 1919 by Bobbs Merrill, also serialized in Munsey's Magazine and republished in a less-costly hardback edition by the A. L. Burt Company. It is a story about a group of treasure hunters on a Pacific island, told from the first person viewpoint of the heroine. It is widely available today as a free e-book from numerous sites, and it has also been reprinted in a paperback edition.

William Brian Hooker was an American poet, educator, lyricist, and librettist. He was born in New York City, the son of Elizabeth Work and William Augustus Hooker, who was a mining engineer for the New York firm of Hooker and Lawrence. His family was well known in Hartford, Connecticut having descended from Thomas Hooker, a prominent Puritan religious and colonial leader who founded the Colony of Connecticut.

Munsey's Magazine was an American magazine founded by Frank Munsey in 1889 as Munsey's Weekly, a humor magazine edited by John Kendrick Bangs. It was unsuccessful, and by late 1891 had lost $100,000. Munsey converted it into an illustrated general monthly in October of that year, retitled Munsey's Magazine and priced at twenty-five cents. Richard Titherington became the editor, and remained in that role throughout the magazine's existence. In 1893 Munsey cut the price to ten cents. This brought him into conflict with the American News Company, which had a near-monopoly on magazine distribution, as they were unwilling to handle the magazine at the price Munsey proposed. Munsey started his own distribution company and was quickly successful: the first ten cent issue began with a print run of 20,000 copies but eventually sold 60,000, and within a year circulation had risen to over a quarter of a million copies.

Famous Fantastic Mysteries was an American science fiction and fantasy pulp magazine published from 1939 to 1953. The editor was Mary Gnaedinger. It was launched by the Munsey Company as a way to reprint the many science fiction and fantasy stories which had appeared over the preceding decades in Munsey magazines such as Argosy. From its first issue, dated September/October 1939, Famous Fantastic Mysteries was an immediate success. Less than a year later, a companion magazine, Fantastic Novels, was launched.

Bernard G. Marshall was an American writer. His historical novel Cedric the Forester was one runner-up for the inaugural Newbery Medal in 1922.

Fantastic Novels was an American science fiction and fantasy pulp magazine published by the Munsey Company of New York from 1940 to 1941, and again by Popular Publications, also of New York, from 1948 to 1951. It was a companion to Famous Fantastic Mysteries. Like that magazine, it mostly reprinted science fiction and fantasy classics from earlier decades, such as novels by A. Merritt, George Allan England, and Victor Rousseau, though it occasionally published reprints of more recent work, such as Earth's Last Citadel, by Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore.