History

The document has its roots in the Polyptych of Pope Gelasius I, created at the end of the 5th century and continued for the next four centuries. [3] The Liber Censuum proper was assembled in 1192 by Cencius Camerarius (future Pope Honorius III), papal chamberlain to Pope Clement III and Pope Celestine III, and his assistant, William Rofio, the clerk of the papal camera. [6] The document compiled information contained in the Collectio canonum of Cardinal Deusdedit (1087), the Liber politicus of the Canon of St. Peter Benedict (c. 1140), dossiers of the former chamberlain Boson (1149–1178), and the Gesta pauperis scolaris of Cardinal Albinus (1188). [3] Albinus' Gesta was the "most ambitious" of the Liber Censuum predecessor records, containing—according to Albinus—"whatever I knew or found in books of antiquities or what I myself heard and saw concerning the rights of St. Peter". [4] The Liber Censuum also incorporates information from a contemporary general census and rent table of church properties organized by diocese, the Ordo romanus (a description of religious ceremonies), as it pertains to the distribution of payments to the curia during such ceremonies, and works of pontifical history such as the Liber pontificalis . [7]

The earliest documentary evidence for the use of such a document of papal property rights goes back even earlier to an 1163/1164 letter from Pope Alexander III to the abbot of Lagny-sur-Marne requesting an annual payment of one ounce of gold, owed according to "a certain work among the books of the apostolic see". [4] Although this specific claim dated to the time of Pope Urban II, the abbot rejected it and there is no evidence Alexander III pursued it further. [4] Such incidences are likely what Cencius refers to in the preface of the Liber Censuum as the "no little damage and loss" incurred by the church as a result of earlier records being "incomplete and neither written nor arranged authentically". [4] Furthermore, the Liber Censuum was compiled at a time when the papal patrimony was threatened by the Staufen emperor and individual payments from sources throughout the continent were being reduced by the evasiveness of payers and the inefficiency of the apostolic camera. [4]

Contents

The eighteen volumes of the Liber Censuum are divided between: census and rent tables (vol. 1–7), lists of bishoprics and monasteries directly administered by the Holy See (vol. 8), the Mirabilia , a mythical description of the city of Rome (vol. 9), [8] a version of the Ordo romanus (vol. 10–11), pontifical chronicles (vol. 12–13), and a chartulary (vol. 14–18). [9]

The dating of the Liber Censuum to 1192 comports with the date given in the work's prologue, although this date may only be accurate for the record of taxes owed to the Holy See. [10] For example, the Vita Gregorii IX was inserted into the codex of the Liber Censuum between 1254 and 1265, likely during the tenure of Pope Gregory IX's nephew Niccolò as camerarius between 1255 and 1261. [11]

The original version of the Liber Censuum by Cardinal Cencius begins:

- Incipit liber censuum Rom. Eccl. a Centio Camerario compositus, secundum antiquorum patrum Regesta et memorialia diversa. A. incarn. dni MCXCII. Pont. Celestini Pp. III. A. II. [1]

The Liber Censuum described itself as an authoritative list of "those monasteries, hospitals [...] cities, castles, manors [...] or those kings and princes belonging to the jurisdiction and property of St. Peter and the holy Roman church and owing census and how much they ought to pay". [6]

The census list included churches, abbeys and bisphorics, as well as some original receipts or payment records. [12]

The value of the rights recorded in the Liber Censuum is difficult to quantify exactly, and in any case, unlikely to have been paid in full. [13] V. Pfaff, estimating historical exchange rates, assessed the value of the revenue cited in the Liber Censuum as 1,214 gold ounces, a sum that would comprise less than 5% of Richard I of England's annual income. [13] The Liber Censuum, however, does not include several sources of papal revenue, in particular those collected in-kind and the revenues of the Basilicas of Rome. [13]

Later editions and legacy

Papal historians regard the Liber Censuum as well-organized compared to the works which preceded it, and it includes empty spaces for anticipated updating. [9] The intent was to allow future camerarii to add future entries "until the end of the world". [6] The original version of the Liber Censuum was identified by Paul Fabre in the Vatican Library (ms Vat. Lat. 8486), with its blank spaces having been exhausted during the pontificate of Cencius (who was elected Pope Honorius III) and five new volumes having been added to the beginning and end of the document. [9] A new version of the Liber Censuum was compiled by Cardinal Nicholas Roselli (d. 1362) in the 14th century. [14]

A 1228 version of the Liber censuum in the library of Florence (ms Riccard. 228) was updated through the Avignon Papacy. [9] By the end of the 13th century the addition of the dossiers of the cities of the Papal States and other papal biographies swelled the document to thirty-three volumes. [9] A copy of the Liber censuum, along with a tiara, was given by Antipope Clement VIII to the legate of Pope Martin V in 1429 as a sign of submission. [9]

Modern, edited versions of the Liber Censuum, reconstructed as their editors thought the original codex of Cencius would have appeared, have been produced by Fabre and Louis Duchesne (1910). [4] Fabre's identification of other portions of the Liber Censuum, for example the alleged acquiescence of King Harthacanute to ecclesiastical taxation, are more controversial. [15]

The Liber Pontificalis is a book of biographies of popes from Saint Peter until the 15th century. The original publication of the Liber Pontificalis stopped with Pope Adrian II (867–872) or Pope Stephen V (885–891), but it was later supplemented in a different style until Pope Eugene IV (1431–1447) and then Pope Pius II (1458–1464). Although quoted virtually uncritically from the 8th to 18th centuries, the Liber Pontificalis has undergone intense modern scholarly scrutiny. The work of the French priest Louis Duchesne, and of others has highlighted some of the underlying redactional motivations of different sections, though such interests are so disparate and varied as to render improbable one popularizer's claim that it is an "unofficial instrument of pontifical propaganda."

Pope Honorius III, born Cencio Savelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 18 July 1216 to his death. A canon at the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, he came to hold a number of important administrative positions, including that of Camerlengo. In 1197, he became tutor to the young Frederick II. As pope, he worked to promote the Fifth Crusade, which had been planned under his predecessor, Innocent III. Honorius repeatedly exhorted King Andrew II of Hungary and Emperor Frederick II to fulfill their vows to participate. He also gave approval to the recently formed Dominican and Franciscan religious orders.

Pope Marinus I was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 882 until his death. Controversially at the time, he was already a bishop when he became pope, and had served as papal legate to Constantinople. He was also erroneously called Martin II leading to the second pope named Martin to take the name Martin IV.

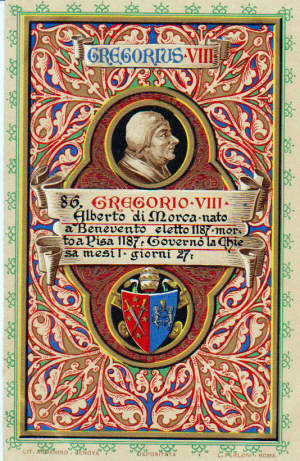

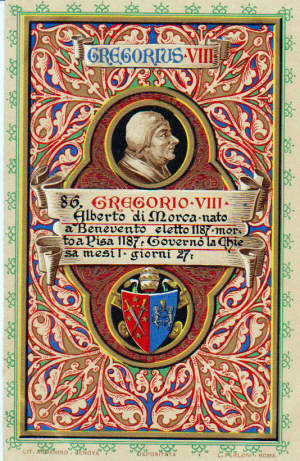

Pope Gregory VIII, born Alberto di Morra, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States for two months in 1187. Becoming Pope after a long diplomatic career as Apostolic Chancellor, he was notable in his brief reign for reconciling the Papacy with the estranged Holy Roman Empire and for initiating the Third Crusade.

Pope Callixtus II or Callistus II, born Guy of Burgundy, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1 February 1119 to his death in 1124. His pontificate was shaped by the Investiture Controversy, which he was able to settle through the Concordat of Worms in 1122.

Lando was the pope from c. September 913 to his death c. March 914. His short pontificate fell during an obscure period in papal and Roman history, the so-called Saeculum obscurum (904–964).

Pope Lucius III, born Ubaldo Allucingoli, reigned from 1 September 1181 to his death in 1185. Born of an aristocratic family of Lucca, prior to being elected pope, he had a long career as a papal diplomat. His papacy was marked by conflicts with Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I, his exile from Rome and the initial preparations for the Third Crusade.

Pope Lucius II, born Gherardo Caccianemici dal Orso, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1144 to his death in 1145. His pontificate was notable for the unrest in Rome associated with the Commune of Rome and its attempts to wrest control of the city from the papacy. He supported Empress Matilda's claim to England in the Anarchy, and had a tense relationship with King Roger II of Sicily.

The Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church is an office of the papal household that administers the property and revenues of the Holy See. Formerly, his responsibilities included the fiscal administration of the Patrimony of Saint Peter. As regulated in the apostolic constitution Pastor bonus of 1988, the Camerlengo is always a cardinal, though this was not the case prior to the 15th century. His heraldic arms are ornamented with two keys – one gold, one silver – in saltire, surmounted by an ombrellino, a canopy or umbrella of alternating red and yellow stripes. These also form part of the coat of arms of the Holy See during a papal interregnum. The Camerlengo has been Kevin Farrell since his appointment by Pope Francis on 14 February 2019. The Vice Camerlengo has been Archbishop Ilson de Jesus Montanari since 1 May 2020.

A papal conclave is a gathering of the College of Cardinals convened to elect a bishop of Rome, also known as the pope. Catholics consider the pope to be the apostolic successor of Saint Peter and the earthly head of the Catholic Church.

A papal renunciation also called a papal abdication, occurs when the current pope of the Catholic Church voluntarily resigns his position. As a pope's time in office has conventionally lasted from his election until his death, a papal renunciation is an uncommon event. Before the 21st century, only five popes unambiguously resigned with historical certainty, all between the 10th and 15th centuries. Additionally, there are disputed claims of four popes having resigned, dating from the 3rd to the 11th centuries; a fifth disputed case may have involved an antipope.

The Apostolic Camera, formerly known as the Papal Treasury, was an office in the Roman Curia. It was the central board of finance in the papal administrative system and at one time was of great importance in the government of the States of the Church and in the administration of justice, led by the Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church, originally known as camerarius (chamberlain).

Introitus et Exitus Cameræ Apostolicæ is a six-hundred-and-six-volume financial record of the Apostolic Camera of the Holy See, from 1279 to 1524, located in the Vatican Secret Archives. The volumes span the reigns of thirty-two popes from Pope Nicholas III to Pope Clement VII. The volumes relating to the Avignon Popes (1305—1387) as well as the following antipopes were moved from Comtat Venaissin to the Secret Archives in 1783.

A cardinal-nephew was a cardinal elevated by a pope who was that cardinal's relative. The practice of creating cardinal-nephews originated in the Middle Ages, and reached its apex during the 16th and 17th centuries. The last cardinal-nephew was named in 1689 and the practice was abolished in 1692. The word nepotism originally referred specifically to this practice, when it appeared in the English language about 1669. From the middle of the Avignon Papacy (1309–1377) until Pope Innocent XII's anti-nepotism bull, Romanum decet pontificem (1692), a pope without a cardinal-nephew was the exception to the rule. Every Renaissance pope who created cardinals appointed a relative to the College of Cardinals, and the nephew was the most common choice, although one of Alexander VI's creations was his own son.

A conclave capitulation was a compact or unilateral contract drawn up by the College of Cardinals during a papal conclave to constrain the actions of the pope elected by the conclave. The legal term capitulation more frequently refers to the commitment of a sovereign state to relinquish jurisdiction within its borders over the subjects of a foreign state. Before balloting began, all cardinals present at the conclave would swear to be bound by its provisions if elected pope. Capitulations were used by the College of Cardinals to assert its collective authority and limit papal supremacy, to "make the Church an oligarchy instead of a monarchy." Similar electoral capitulations were used on occasion from the 14th to the 17th centuries in Northern and Central Europe to constrain an elected king, emperor, prince, or bishop.

Albinus was an Italian Cardinal of the late twelfth century. A native of Milan, or perhaps of Gaeta, he became an Augustinian regular canon.

Papal appointment was a medieval method of selecting the Pope. Popes have always been selected by a council of Church fathers; however, Papal selection before 1059 was often characterized by confirmation or nomination by secular European rulers or by the preceding pope. The later procedures of the Papal conclave are in large part designed to prohibit interference of secular rulers, which to some extent characterized the first millennium of the Roman Catholic Church, e. g. in practices such as the creation of crown-cardinals and the claimed but invalid jus exclusivae. Appointment may have taken several forms, with a variety of roles for the laity and civic leaders, Byzantine and Germanic emperors, and noble Roman families. The role of the election vis-a-vis the general population and the clergy was prone to vary considerably, with a nomination carrying weight that ranged from nearly determinative to merely suggestive, or as ratification of a concluded election.

From 756 to 857, the papacy shifted from the influence of the Byzantine Empire to that of the kings of the Franks. Pepin the Short, Charlemagne, and Louis the Pious had considerable influence in the selection and administration of popes. The "Donation of Pepin" (756) ratified a new period of papal rule in central Italy, which became known as the Papal States.