Jenny Holzer is an American neo-conceptual artist, based in Hoosick, New York. The main focus of her work is the delivery of words and ideas in public spaces and includes large-scale installations, advertising billboards, projections on buildings and other structures, and illuminated electronic displays.

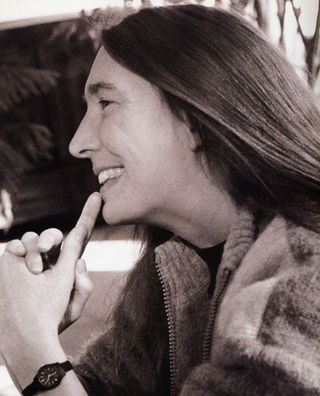

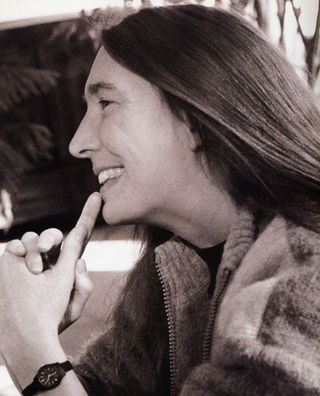

Catherine Sue Opie is an American fine art photographer and educator. She lives and works in Los Angeles, as a professor of photography at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Michael Kelley was an American artist whose work involved found objects, textile banners, drawings, assemblage, collage, performance, photography, sound and video. He also worked on curatorial projects; collaborated with many other artists and musicians; and left a formidable body of critical and creative writing. He often worked collaboratively and had produced projects with artists Paul McCarthy, Tony Oursler, and John Miller. Writing in The New York Times, in 2012, Holland Cotter described the artist as "one of the most influential American artists of the past quarter century and a pungent commentator on American class, popular culture and youthful rebellion."

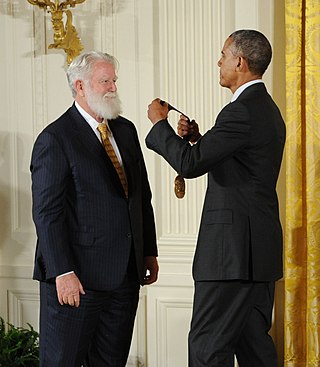

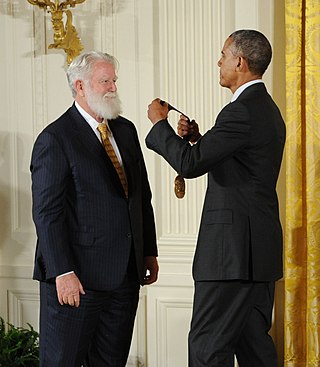

James Turrell is an American artist known for his work within the Light and Space movement. He is considered the "master of light" often creating art installations that mix natural light with artificial color through openings in ceilings thereby transforming internal spaces by ever shifting and changing color.

Rebecca Horn was a German visual artist best known for her installation art, film directing and body modifications such as Einhorn (Unicorn), a body-suit with a very large horn projecting vertically from the headpiece. While living in Paris and Berlin, she worked in film, sculpture and performance, directing the films Der Eintänzer (1978), La ferdinanda: Sonate für eine Medici-Villa (1982) and Buster's Bedroom (1990).

Joan Jonas is an American visual artist and a pioneer of video and performance art, "a central figure in the performance art movement of the late 1960s". Jonas' projects and experiments were influential in the creation of video performance art as a medium. Her influences also extended to conceptual art, theatre, performance art and other visual media. She lives and works in New York and Nova Scotia, Canada.

Dorothy Jeakins was an American costume designer.

Hannah Wilke (born Arlene Hannah Butter; was an American painter, sculptor, photographer, video artist and performance artist. Her work is known for exploring issues of feminism, sexuality and femininity.

Rineke Dijkstra HonFRPS is a Dutch photographer. She lives and works in Amsterdam. Dijkstra has been awarded an Honorary Fellowship of the Royal Photographic Society, the 1999 Citibank Private Bank Photography Prize and the 2017 Hasselblad Award.

Roni Horn is an American visual artist and writer. The granddaughter of Eastern European immigrants, she was born in New York City, where she lives and works. She is currently represented by Xavier Hufkens in Brussels and Hauser & Wirth. She is openly gay.

Judy Pfaff is an American artist known mainly for installation art and sculptures, though she also produces paintings and prints. Pfaff has received numerous awards for her work, including a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Fellowship in 2004 and grants from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation (1983) and the National Endowment for the Arts. Major exhibitions of her work have been held at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, the Denver Art Museum and Saint Louis Art Museum. In 2013 she was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Video interviews can be found on Art 21, Miles McEnery Gallery, MoMa, Mount Holyoke College Art Museum and other sources.

Hanne Darboven was a German conceptual artist, best known for her large-scale minimalist installations consisting of handwritten tables of numbers.

Alexandra Grant is an American visual artist who examines language and written texts through painting, drawing, sculpture, video, and other media. She uses language and exchanges with writers as a source for much of that work. Grant examines the process of writing and ideas based in linguistic theory as it connects to art and creates visual images inspired by text and collaborative group installations based on that process. She is based in Los Angeles.

Liz Larner is an American installation artist and sculptor living and working in Los Angeles.

Nicole Eisenman is a French-born American artist known for her oil paintings and sculptures. She has been awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship (1996), the Carnegie Prize (2013), and has thrice been included in the Whitney Biennial. On September 29, 2015, she won a MacArthur Fellowship award for "restoring the representation of the human form a cultural significance that had waned during the ascendancy of abstraction in the 20th century."

Kim Victoria Abeles is an American interdisciplinary artist and professor emeritus. She was born in Richmond Heights, Missouri, and currently lives in Los Angeles. She is described as an activist artist because of her work's social and political nature. In her work, she’s able to express these issues and shine a light on them to larger audiences. She’s able to show the significance of the issues by creating a piece that involves an object and adds the struggle attached to it, which represents what is happening in current events. She is also known for her feminist works. Abeles has exhibited her works in 22 countries and has received a number of significant awards including a Guggenheim Fellowship. Aside from her work as an artist, she was a professor in public art, sculpture, and drawing at California State University, Northridge from 1998 to 2009, after which she became professor emerita in 2010.

Robin Coste Lewis is an American poet, artist, and scholar. Poet Laureate Emeritus of Los Angeles, Lewis's debut poetry collection, Voyage of the Sable Venus and Other Poems won the National Book Award for Poetry in 2015––the first time a poetry debut by an African-American had ever won the prize in the National Book Foundation's history, and the first time any debut had won the award since 1974. Critics called the collection "A masterpiece", "Surpassing imagination, maturity, and aesthetic dazzle", "remarkable hopefulness ... in the face of what would make most rage and/or collapse", "formally polished, emotionally raw, and wholly exquisite". Voyage of the Sable Venus was also a finalist for the LA Times Book Prize, the Hurston-Wright Award, and the California Book Award. The Paris Review, The New Yorker, The New York Times, Buzz Feed, and Entropy Magazine all named Voyage one of the best poetry collections of the year. Flavorwire named the collection one of the 10 must-read books about art. And Literary Hub named Voyage one of the "Most Important Books of the Last Twenty Years". In 2018, MoMA commissioned both Lewis and Kevin Young to write a series of poems to accompany Robert Rauschenberg's drawings in the book Thirty-Four Illustrations of Dante's Inferno. Lewis is also the author of Inhabitants and Visitors, a chapbook published by Clockshop and the Huntington Library and Museum. Her photo-text collection, To the Realization of Perfect Helplessness, was published to great acclaim by Knopf in 2022. Awards included the PEN Award for Poetry, the NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work, and the California Book Award (finalist). Her fifth book, Archive of Desire, written in honor of Constantine P. Cavafy, is forthcoming by Knopf in 2025.

Steffani Jemison is an American artist, writer, and educator. Her videos and multimedia projects explore the relationship between Black embodiment, sound cultures, and vernacular practices to modernism and conceptual art. Her work has been shown at the Museum of Modern Art, Brooklyn Museum, Guggenheim Museum, Whitney Museum, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, and other U.S. and international venues. She is based in Brooklyn, New York and is represented by Greene Naftali, New York and Annet Gelink, Amsterdam.

Caitlin Cherry is an African-American painter, sculptor, and educator.

Harriet Korman is an American abstract painter based in New York City, who first gained attention in the early 1970s. She is known for work that embraces improvisation and experimentation within a framework of self-imposed limitations that include simplicity of means, purity of color, and a strict rejection of allusion, illusion, naturalistic light and space, or other translations of reality. Writer John Yau describes Korman as "a pure abstract artist, one who doesn’t rely on a visual hook, cultural association, or anything that smacks of essentialization or the spiritual," a position he suggests few post-Warhol painters have taken. While Korman's work may suggest early twentieth-century abstraction, critics such as Roberta Smith locate its roots among a cohort of early-1970s women artists who sought to reinvent painting using strategies from Process Art, then most associated with sculpture, installation art and performance. Since the 1990s, critics and curators have championed this early work as unjustifiably neglected by a male-dominated 1970s art market and deserving of rediscovery.