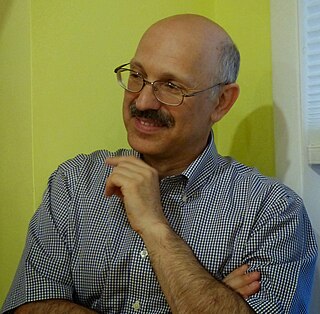

Loren R. Graham (born June 29, 1933, in Hymera, Indiana) is an American historian of science, particularly science in Russia.

Loren R. Graham (born June 29, 1933, in Hymera, Indiana) is an American historian of science, particularly science in Russia.

He has taught and published at Indiana University, Columbia University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Harvard University, where he is currently a research associate. He was a participant in one of the first academic exchange programs between the United States and the Soviet Union, studying at Moscow University in 1960-61.

He wrote a popular book on Native American history (A Face in the Rock) and a memoir (Moscow Stories) which describes his youth in the United States and his adventures in Russia. He has also been a strong supporter of human rights and scholarship. He was a member of the board of trustees of the Soros Foundation.

For many years he has been a member of the Governing Council of the Program on Basic Research and Higher Education, which supports the combining of research and teaching in Russian universities and is financially supported by the MacArthur Foundation, the Carnegie Corporation, the Russian Ministry of Science and Education, and local groups in Russia. He is a member of the advisory council of the U.S. Civilian Research & Development Foundation, which supports international scientific collaboration.

For many years he was a member of the board of trustees of the European University at St. Petersburg and still serves on the board of a body raising money for that university. He donated several thousand books from his library to the European University which has established a special collection in his name.

In much of his work in the history of science, Graham has demonstrated the influence of social context on science, even its theoretical structure. For example, in his Science and Philosophy in the Soviet Union (which was a finalist for a National Book Award) he delineated the influence of Marxism on science in Russia — in some cases, such as the Lysenko Affair, deleterious, but, in other cases, particularly in physics, psychology, and origin of life studies, positive.

In addition to writing on the history of scientific theories, Graham has written much on the organization of science in Russia and the Soviet Union, including a book on the early history of the Soviet Academy of Sciences (The Soviet Academy of Sciences and the Communist Party) and a more recent one on the situation of science in Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union (Science in the New Russia; co-written with Irina Dezhina).

Graham earned his B.A. in chemical engineering at Purdue University and his M.A. and doctorate degree in history at Columbia University. [1]

In 1996 he received the George Sarton Medal of the History of Science Society and in 2000 he received the Follo Award of the Michigan Historical Society for his contributions to Michigan history.[ citation needed ]

Graham is a member of a number of honorary societies, both American and foreign, including the American Philosophical Society, [2] the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the Russian Academy of Natural Science. His books have been published in English, Italian, German, Russian, Spanish, French, Japanese, Greek, Persian, Korean and Chinese. In 2012, he was awarded a medal by the Russian Academy of Sciences at a ceremony in Moscow for "contributions to the history of science".[ citation needed ]

Graham's wife Patricia Graham is a prominent historian of education and a former dean at Harvard University.[ citation needed ]

Biographical material and professional details for Loren Graham may be found in:

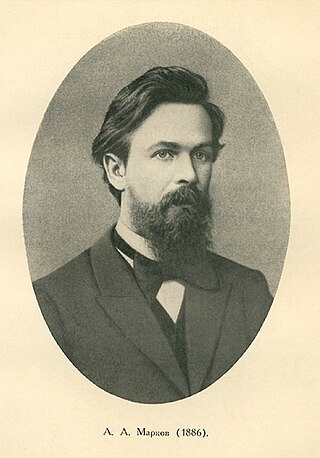

Andrey Andreyevich Markov was a Russian mathematician best known for his work on stochastic processes. A primary subject of his research later became known as the Markov chain. He was also a strong, close to master-level chess player.

Trofim Denisovich Lysenko was a Soviet agronomist and pseudoscientist. He was a strong proponent of Lamarckism, and rejected Mendelian genetics in favour of his own idiosyncratic, pseudoscientific ideas later termed Lysenkoism.

Andrey Nikolaevich Kolmogorov was a Soviet mathematician who contributed to the mathematics of probability theory, topology, intuitionistic logic, turbulence, classical mechanics, algorithmic information theory and computational complexity.

Vitaly Lazarevich Ginzburg, ForMemRS was a Russian physicist who was honored with the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2003, together with Alexei Abrikosov and Anthony Leggett for their "pioneering contributions to the theory of superconductors and superfluids."

Lysenkoism was a political campaign led by Soviet biologist Trofim Lysenko against genetics and science-based agriculture in the mid-20th century, rejecting natural selection in favour of a form of Lamarckism, as well as expanding upon the techniques of vernalization and grafting.

Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov was a Russian and Soviet agronomist, botanist and geneticist who identified the centers of origin of cultivated plants. He devoted his life to the study and improvement of wheat, maize and other cereal crops that sustain the global population.

Nikolai Nikolayevich Luzin was a Soviet and Russian mathematician known for his work in descriptive set theory and aspects of mathematical analysis with strong connections to point-set topology. He was the eponym of Luzitania, a loose group of young Moscow mathematicians of the first half of the 1920s. They adopted his set-theoretic orientation, and went on to apply it in other areas of mathematics.

Pavel Sergeyevich Alexandrov, sometimes romanized Paul Alexandroff, was a Soviet mathematician. He wrote roughly three hundred papers, making important contributions to set theory and topology. In topology, the Alexandroff compactification and the Alexandrov topology are named after him.

Ilya Piatetski-Shapiro was a Soviet-born Israeli mathematician. During a career that spanned 60 years he made major contributions to applied science as well as pure mathematics. In his last forty years his research focused on pure mathematics; in particular, analytic number theory, group representations and algebraic geometry. His main contribution and impact was in the area of automorphic forms and L-functions.

Bourgeois pseudoscience was a term of condemnation in the Soviet Union for certain scientific disciplines that were deemed unacceptable from an ideological point of view due to their incompatibility with Marxism–Leninism. At various times pronounced "bourgeois pseudosciences" were: Mendelian genetics, cybernetics, quantum physics, theory of relativity, sociology and particular directions in comparative linguistics.

Many fields of scientific research in the Soviet Union were banned or suppressed with various justifications. All humanities and social sciences were tested for strict accordance with historical materialism. These tests served as a cover for political suppression of scientists who engaged in research labeled as "idealistic" or "bourgeois". Many scientists were fired, others were arrested and sent to Gulags. The suppression of scientific research began during the Stalin era and continued after his death.

Science and technology in the Soviet Union served as an important part of national politics, practices, and identity. From the time of Lenin until the dissolution of the USSR in the early 1990s, both science and technology were intimately linked to the ideology and practical functioning of the Soviet state and were pursued along paths both similar and distinct from models in other countries. Many great scientists who worked in Imperial Russia, such as Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, continued work in the USSR and gave birth to Soviet science.

Zhores Aleksandrovich Medvedev was a Russian agronomist, biologist, historian and dissident. His twin brother is the historian Roy Medvedev.

Imiaslavie, among critics also known as imyabozhie or imyabozhnichestvo, and also referred to as onomatodoxy was a mystical-dogmatic movement in Russian Orthodoxy, the main position of which was the statement of the indissoluble connection between the name of God as the energy and action of God and God Himself. The imiaslavie movement emerged early in the 20th century, but both proponents and opponents cite alleged antecedents throughout the history of Christianity. Advocates claim that the idea is traceable to the Church Fathers, while opponents claim to trace it to ancient heresiarchs.

Ideological repression in the Soviet Union targeted various worldviews and the corresponding categories of people.

The Communist Academy was a higher educational establishment and research institute based in Moscow. It included scientific institutes of philosophy, history, literature, art and language, Soviet construction and law, world economy and world politics, economics, agrarian research as well as institutes of natural and social science. It was intended to allow Marxists to research problems independent of, and implicitly in rivalry with, the Academy of Sciences which long pre-existed the October Revolution and the subsequent formation of the Soviet Union.

Vyacheslav (Slava) Alexandrovich Gerovitch is an American historian of science of Russian origin, considered a leading scholar on Soviet space program history in the US and Cybernetics in the Soviet Union.

Alexander S. Vucinich was an American historian. He taught at the department of history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania from 1976 until his retirement in 1985. He also taught at San Jose State College (1950–64), the University of Illinois (1964–70), and the University of Texas (1970–76). After his retirement he and his wife Dorothy moved to Berkeley, California, where he participated in the activities of Berkeley's Institute of Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies. His field of research was the history of science and social thought in Russia and the Soviet Union.

Antisemitism in Soviet mathematics was a manifestation of hostility, prejudice and discrimination in the Soviet Union towards Jews in the scientific and educational environment related to mathematics.

David Joravsky was an American professor of history, specializing in the Soviet Union's academics in the biological sciences and related politics.