Liu Mingzhao, courtesy name Bocheng, more commonly known as Liu Bocheng, was a Chinese military commander and a Marshal of the People's Republic of China.

Luo or Lo refers to the Mandarin romanizations of the Chinese surnames 羅 and 駱. Of the two surnames, wikt:罗 is much more common among Chinese people. According to the Cantonese pronunciation, it can also refer to 盧.

Yang Hucheng was a Chinese general during the Warlord Era of Republican China and Kuomintang general during the Chinese Civil War.

Li Kenong was a Chinese general and politician, one of the creators of the security and intelligence apparatus of both the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the People's Liberation Army. Notably, he served as Director of the Central Investigation Department, Deputy Chief of the PLA General Staff Department and Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs and was awarded the rank of General in 1955.

The Peasant Movement Training Institute or Peasant Training School was a school in Guangzhou, China, operated from 1923 to 1926 during the First United Front between the Nationalists and Communists. It was located in a former Confucian temple built in the 14th century. The site now houses a museum to Guangzhou's revolutionary past.

The Jiangxi Soviet was a soviet governed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that existed between 1931 and 1934. It was the largest component of the Chinese Soviet Republic and home to its capital, Ruijin. At the time, the CCP was engaged in a rural insurgency against the Kuomintang-controlled Nationalist Government as part of the Chinese Civil War. CCP leaders Mao Zedong and Zhu De chose to create the soviet in the rugged Jinggang Mountains on the border of Jiangxi and Fujian because of its remote location and defensible terrain. The First Red Front Army successfully repulsed a series of encirclement campaigns by the Kuomintang's National Revolutionary Army (NRA) during the first few years of the Soviet's existence, but they were eventually defeated by the NRA's fifth attempt in 1934-35. After the Jiangxi Soviet was defeated militarily, the CCP began the Long March towards a new base area in the northwest.

Luocheng(Chinese: t:羅城,s:罗城,pLuóchéng,lit. "Enclosing Wall" or "City"), formerly romanized as Lo-ch'eng, may refer to:

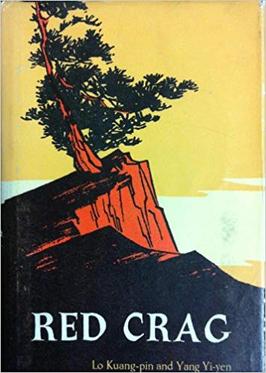

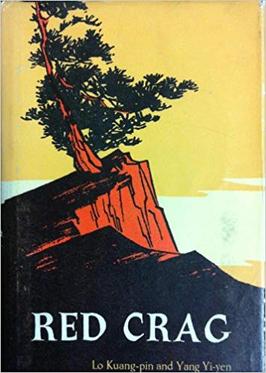

Red Crag or Red Rock was a 1961 novel based partly on fact by Chinese authors Luo Guangbin and Yang Yiyan, who were former inmates in a Kuomintang prison in Sichuan. It was set in Chongqing during the Chinese Civil War in 1949, and featured underground communist agents under the command of Zhou Enlai fighting an espionage battle against the Kuomintang.

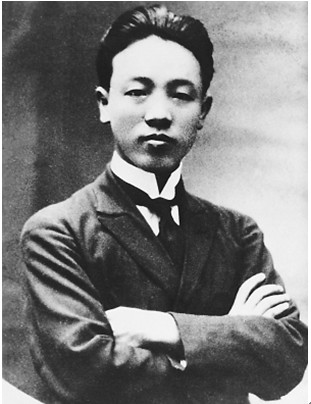

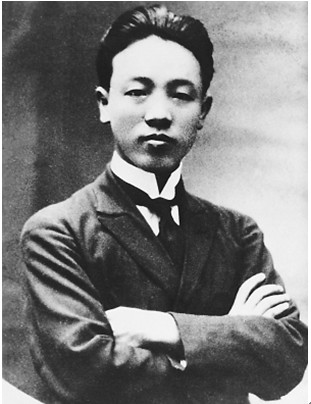

Zhao Shiyan was a Chinese Communist revolutionary and former Chinese premier Li Peng's uncle.

Jiang Zhuyun was a Chinese communist revolutionary. She is the basis of the character of Jiang Xueqin, or "Sister Jiang" in the semi-fictional novel Red Crag.

Luo Niansheng was a Chinese translator. He was known for translating Ancient Greek literature into Chinese.

Hu Di was a Chinese filmmaker and Communist secret agent during the Republic of China era. After the Kuomintang (KMT) began the Shanghai massacre in 1927, Hu worked as a mole in the Kuomintang secret service, together with Qian Zhuangfei and Li Kenong. Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai called them "the three most distinguished intelligence workers of the Party." Hu was executed in September 1935 by renegade Chinese Communist Party commander Zhang Guotao during the Long March.

Baigongguan and Zhazidong were Chinese concentration camps that opened in 1943 and were used by the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Sino-American Cooperative Organization (SACO) to gather intelligence about the Empire of Japan during the Second Sino-Japanese War. The camps were located in southwest China, in the Gele Mountains of Chongqing. In 1947, the camps were reopened by the Kuomintang to hold captured communist politicians of the Republic of China. After the People's Liberation Army started its advance on the area and threatened the liberation of the camps, General Dai Li of the Kuomintang authorized the camps to serve as the execution sites of the communist politicians in 1949.

The Jiaochangkou incident was a political riot that took place on 10 February 1946 in Jiaochangkou in the centre of Chongqing City, which was the wartime capital of the Republic of China and declared the second capital after the war by the Nationalist -led government. During 1945–46, KMT and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) held political negotiations over the future of China in the city. The incident marked an open rivalry between the two parties, which eventually led to a civil war that ended up with a CCP victory.

Luo Wen is a Chinese executive and politician who is the current director of the State Administration for Market Regulation, in office since July 2022.

The Xifeng concentration camp was a concentration camp in Xifeng County, Guizhou, China. Established by the Kuomintang (KMT) following the Marco Polo Bridge incident in 1937, the camp – the largest of the KMT's internment sites – was constructed primarily to discipline staff of the Bureau of Investigation and Statistics (Juntong) and hold members of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Initially modelled after Nazi concentration camps, it was led from 1938 through 1941 by He Zizhen, who strictly controlled prisoners and guards. When Zhou Yanghao assumed leadership of the camp in March 1941, he reformed the camp along the Soviet philosophy of "corrective labour" while simultaneously reorganizing camp administration. The camp was dissolved in 1946, and in 1988 the former site was designated a National Key Cultural Relic. Since 1997, it has been a destination for red tourism.

Song Qiyun was a Chinese journalist and member of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Born in Pi County, Jiangsu, to a poor family, he attended the Sixth Normal School but left teaching in 1926 to join the military. As a member of the CCP, he infiltrated the police to gather information on the Kuomintang (KMT) before ultimately joining the 17th Route Army under Yang Hucheng. In this capacity, he served as the editor-in-chief of the Northwest Cultural Daily from 1930 to 1937. Detained by the KMT in 1941, he was imprisoned with his wife Xu Linxia and youngest son Song Zhenzhong, with whom he was executed in 1949.

Song Zhenzhong, popularly known as Little Radish Head, was the son of Chinese Communist Party members Song Qiyun and Xu Linxia. Held by the Kuomintang for the majority of his life, he was executed together with his parents as part of a mass killing of detainees. He has been identified as "China's youngest martyr", and featured extensively in film and literature. He has also been commemorated with multiple monuments.

Xu Linxia was a Chinese communist. Born in Pi County, she attended the No. 3 Normal School before joining the Kuomintang (KMT). After the dissolution of the First United Front, she joined the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), becoming a leader of its women's branch in Pi. She married Song Qiyun in 1928, and the couple had seven children. Xu was detained by the KMT in 1941, together with her youngest son Song Zhenzhong; her husband was also arrested that year. The three were executed in 1949. Xu has been recognized by the CCP with the title of revolutionary martyr.

Eternity in Flames, also known as Red Crag, is a black-and-white 1965 Chinese-language film directed by Shui Hua. Starring Yu Lan and Zhao Dan, it tells the story of a young woman who leads a band of Communist guerillas after the death of her husband. After being betrayed, she is imprisoned with other Chinese Communist Party (CCP) members by the Kuomintang (KMT). Unwilling to betray her cause, she is executed shortly before a mass escape.