Edema, also spelled oedema, and also known as fluid retention, dropsy and hydropsy, is the build-up of fluid in the body's tissue, a type of swelling. Most commonly, the legs or arms are affected. Symptoms may include skin that feels tight, the area feeling heavy, and joint stiffness. Other symptoms depend on the underlying cause.

The lymphatic system, or lymphoid system, is an organ system in vertebrates that is part of the immune system and complementary to the circulatory system. It consists of a large network of lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, lymphoid organs, lymphatic tissue and lymph. Lymph is a clear fluid carried by the lymphatic vessels back to the heart for re-circulation. The Latin word for lymph, lympha, refers to the deity of fresh water, "Lympha".

The pleural cavity, or pleural space, is the potential space between the pleurae of the pleural sac that surrounds each lung. A small amount of serous pleural fluid is maintained in the pleural cavity to enable lubrication between the membranes, and also to create a pressure gradient.

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity (pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant dull ache. Other symptoms may include shortness of breath, cough, fever, or weight loss, depending on the underlying cause.

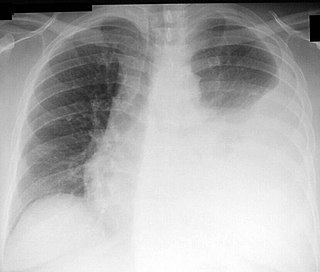

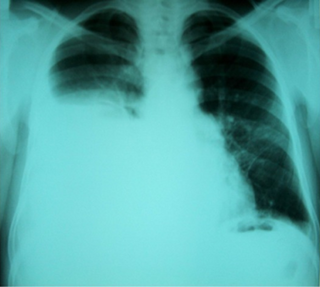

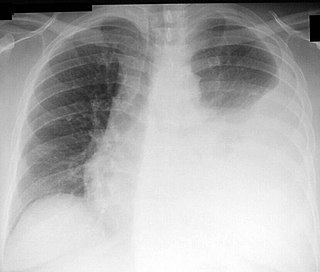

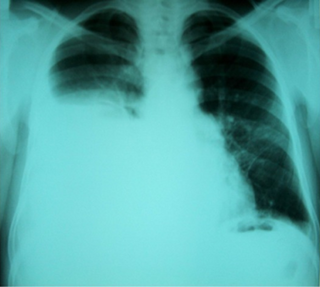

A pleural effusion is accumulation of excessive fluid in the pleural space, the potential space that surrounds each lung. Under normal conditions, pleural fluid is secreted by the parietal pleural capillaries at a rate of 0.6 millilitre per kilogram weight per hour, and is cleared by lymphatic absorption leaving behind only 5–15 millilitres of fluid, which helps to maintain a functional vacuum between the parietal and visceral pleurae. Excess fluid within the pleural space can impair inspiration by upsetting the functional vacuum and hydrostatically increasing the resistance against lung expansion, resulting in a fully or partially collapsed lung.

Chyle is a milky bodily fluid consisting of lymph and emulsified fats, or free fatty acids (FFAs). It is formed in the small intestine during digestion of fatty foods, and taken up by lymph vessels specifically known as lacteals. The lipids in the chyle are colloidally suspended in chylomicrons.

A chest radiograph, chest X-ray (CXR), or chest film is a projection radiograph of the chest used to diagnose conditions affecting the chest, its contents, and nearby structures. Chest radiographs are the most common film taken in medicine.

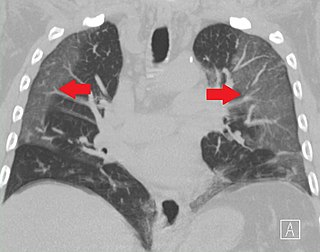

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a rare, progressive and systemic disease that typically results in cystic lung destruction. It predominantly affects women, especially during childbearing years. The term sporadic LAM is used for patients with LAM not associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), while TSC-LAM refers to LAM that is associated with TSC.

Paragonimus westermani is the most common species of lung fluke that infects humans, causing paragonimiasis. Human infections are most common in eastern Asia and in South America. Paragonimiasis may present as a sub-acute to chronic inflammatory disease of the lung. It was discovered by Dutch zoologist Coenraad Kerbert in 1878.

A chylothorax is an abnormal accumulation of chyle, a type of lipid-rich lymph, in the pleural space surrounding the lung. The lymphatic vessels of the digestive system normally return lipids absorbed from the small bowel via the thoracic duct, which ascends behind the esophagus to drain into the left brachiocephalic vein. If normal thoracic duct drainage is disrupted, either due to obstruction or rupture, chyle can leak and accumulate within the negative-pressured pleural space. In people on a normal diet, this fluid collection can sometimes be identified by its turbid, milky white appearance, since chyle contains emulsified triglycerides.

Thoracentesis, also known as thoracocentesis, pleural tap, needle thoracostomy, or needle decompression, is an invasive medical procedure to remove fluid or air from the pleural space for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. A cannula, or hollow needle, is carefully introduced into the thorax, generally after administration of local anesthesia. The procedure was first performed by Morrill Wyman in 1850 and then described by Henry Ingersoll Bowditch in 1852.

Yellow nail syndrome, also known as "primary lymphedema associated with yellow nails and pleural effusion", is a very rare medical syndrome that includes pleural effusions, lymphedema and yellow dystrophic nails. Approximately 40% will also have bronchiectasis. It is also associated with chronic sinusitis and persistent coughing. It usually affects adults.

Mediastinitis is inflammation of the tissues in the mid-chest, or mediastinum. It can be either acute or chronic. It is thought to be due to four different etiologies:

Gorham's disease, also known as Gorham vanishing bone disease and phantom bone disease, is a very rare skeletal condition of unknown cause. It is characterized by the uncontrolled proliferation of distended, thin-walled vascular or lymphatic channels within bone, which leads to resorption and replacement of bone with angiomas and/or fibrosis.

Pleural disease occurs in the pleural space, which is the thin fluid-filled area in between the two pulmonary pleurae in the human body. There are several disorders and complications that can occur within the pleural area, and the surrounding tissues in the lung.

Obstructive shock is one of the four types of shock, caused by a physical obstruction in the flow of blood. Obstruction can occur at the level of the great vessels or the heart itself. Causes include pulmonary embolism, cardiac tamponade, and tension pneumothorax. These are all life-threatening. Symptoms may include shortness of breath, weakness, or altered mental status. Low blood pressure and tachycardia are often seen in shock. Other symptoms depend on the underlying cause.

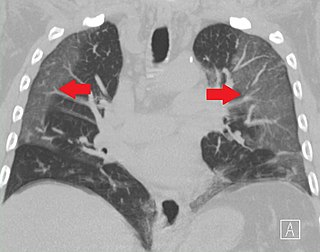

Ground-glass opacity (GGO) is a finding seen on chest x-ray (radiograph) or computed tomography (CT) imaging of the lungs. It is typically defined as an area of hazy opacification (x-ray) or increased attenuation (CT) due to air displacement by fluid, airway collapse, fibrosis, or a neoplastic process. When a substance other than air fills an area of the lung it increases that area's density. On both x-ray and CT, this appears more grey or hazy as opposed to the normally dark-appearing lungs. Although it can sometimes be seen in normal lungs, common pathologic causes include infections, interstitial lung disease, and pulmonary edema.

Tumor-like disorders of the lung pleura are a group of conditions that on initial radiological studies might be confused with malignant lesions. Radiologists must be aware of these conditions in order to avoid misdiagnosing patients. Examples of such lesions are: pleural plaques, thoracic splenosis, catamenial pneumothorax, pleural pseudotumor, diffuse pleural thickening, diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis and Erdheim–Chester disease.

Asbestos-related diseases are disorders of the lung and pleura caused by the inhalation of asbestos fibres. Asbestos-related diseases include non-malignant disorders such as asbestosis, diffuse pleural thickening, pleural plaques, pleural effusion, rounded atelectasis and malignancies such as lung cancer and malignant mesothelioma.

Hepatic hydrothorax is a rare form of pleural effusion that occurs in people with liver cirrhosis. It is defined as an effusion of over 500 mL in people with liver cirrhosis that is not caused by heart, lung, or pleural disease. It is found in 5–10% of people with liver cirrhosis and 2–3% of people with pleural effusions. In cases of decompensated liver cirrhosis, prevalence rises significantly up to 90%. Over 85% of cases occurring on the right, 13% on the left, and 2% on both. Although it is most common in people with severe ascites, it can also occur in people with mild or no ascites. Symptoms are not specific and mostly involve the respiratory system.