Literature of Kashmir has a long history, the oldest texts having been composed in the Sanskrit language. Early names include Patanjali, the author of the Mahābhāṣya commentary on Pāṇini's grammar, suggested by some to have been the same to write the Hindu treatise known as the Yogasutra, and Dridhbala, who revised the Charaka Samhita of Ayurveda.

Awadh, known in British historical texts as Avadh or Oudh, is a historical region in northern India, now constituting the northeastern portion of Uttar Pradesh. It is roughly synonymous with the ancient Kosala region of Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain scriptures.

Faizabad is a city located in Ayodhya district in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. It is situated on the southern bank of the River Saryu about 6.5 km from Ayodhya City, the district headquarter, 130 km east of the state capital Lucknow. Faizabad was the first capital of the Nawabs of Awadh and has monuments built by those Nawabs, like the Tomb of Bahu Begum, Gulab Bari. It was also the headquarters of Faizabad district and Faizabad division before November 2018. Faizabad is a twin city of Ayodhya and it is administered by Ayodhya Municipal Corporation.

Agha Shahid Ali Qizilbash was an Indian-born American poet. Born into a Kashmiri Muslim family, Ali immigrated to the United States and became affiliated with the literary movement known as New Formalism in American poetry. His collections include A Walk Through the Yellow Pages, The Half-Inch Himalayas,A Nostalgist's Map of America, The Country Without a Post Office, and Rooms Are Never Finished, the latter a finalist for the National Book Award in 2001.

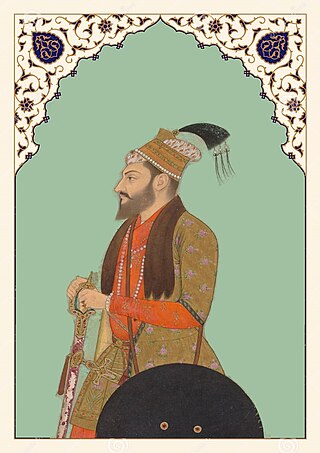

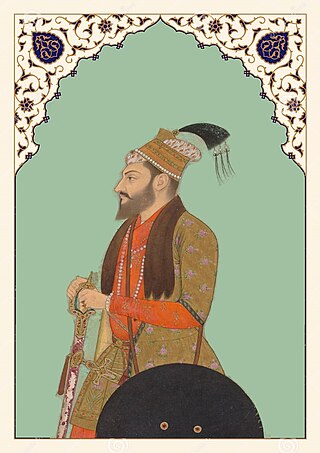

Mirza Muhammad Murad Bakhsh was a Mughal prince and the youngest surviving son of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan and Empress Mumtaz Mahal. He was the Subahdar of Balkh, till he was replaced by his elder brother Aurangzeb in the year 1647.

Begum Hazrat Mahal, also known as the Begum of Awadh, was the second wife of Nawab of Awadh Wajid Ali Shah, and the regent of Awadh in 1857–1858. She is known for the leading role she had in the rebellion against the British East India Company during the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

Mirza Asaf-ud-Daula was the Nawab wazir of Oudh ratified by Shah Alam II, from 26 January 1775 to 21 September 1797, and the son of Shuja-ud-Dowlah. His mother and grandmother were the Begums of Oudh.

Mirza Wajid Ali Shah was the eleventh and last King of Awadh, holding the position for 9 years, from 13 February 1847 to 11 February 1856.

The Capture of Lucknow was a battle of Indian rebellion of 1857. The British recaptured the city of Lucknow which they had abandoned in the previous winter after the relief of a besieged garrison in the Residency, and destroyed the organised resistance by the rebels in the Kingdom of Awadh.

Saiyid Nurul Hasan FRHistS,FRAS was an Indian historian and an elder statesman in the Government of India. A member of the Rajya Sabha, he was the Union Minister of State of Education, Social Welfare and Culture Government of India (1971–1977) and the Governor of West Bengal and Odisha (1986–1993).

The Nawab of Awadh or Nawab of Oudh was the title of the rulers of Kingdom of Awadh in northern India during the 18th and 19th centuries. The Nawabs of Awadh belonged to an Iranian dynasty of Sayyid origin from Nishapur, Iran. In 1724, Nawab Sa'adat Khan established the Kingdom of Awadh with their capital in Faizabad and Lucknow.

Moazzam Jah, Walashan Shahzada Nawab Mir Sir Shuja’at ‘Ali Khan Siddiqui Bahadur, KCIE, was the son of the last Nizam of Hyderabad, Osman Ali Khan, Asaf Jah VII and his first wife Azamunnisa Begum.

Ghazi-ud-Din Haidar Shah was the last nawab wazir of Oudh from 11 July 1814 to 19 October 1818, and first King of Oudh from 19 October 1818 to 19 October 1827.

Birjis Qadr was the son of Wajid Ali Shah, the last Nawab of Awadh. He was a put on the throne after his father had been deposed by the East India Company in 1856 under the terms of the Doctrine of lapse and Oudh State was annexed into the Bengal Presidency.

Nawab Murtaza Ali Khan Bahadur, MBE, NH, NI was the titular Nawab of Rampur from 1966 to his death in 1982, succeeding his father, Nawab Raza Ali Khan Bahadur, and was succeeded in 1982 as titular Nawab by his younger brother Zulfikar Ali Khan.

Badshah Begum was the first wife and chief consort of the Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah. She is popularly known by her title Malika-uz-Zamani which was conferred upon her by her husband, immediately after their marriage.

Malcha Mahal, also known as Wilayat Mahal, is a Tughlaq era hunting lodge in the Chanakyapuri area of New Delhi, India next to the Delhi Earth Station of the Indian Space Research Organisation. It was built by Firuz Shah Tughlaq, who reigned over the Sultanate of Delhi, in 1325. It came to be known as Wilayat Mahal after the self-proclaimed "Begum Wilayat Mahal" of Awadh, who claimed to be a member of the Royal family of Oudh and was reportedly given the place by the Government of India in May 1985. On 10 September 1993, Wilayat died by suicide at the age of 62. The Royal House of Awadh claims that the family engaged in fraudulent activities, having been cited by an investigative journalist for the New York Times.

The Oudh State was a Mughal subah, then an independent kingdom, and lastly a princely state in the Awadh region of North India until its annexation by the British in 1856. The name Oudh, now obsolete, was once the anglicized name of the state, also written historically as Oudhe.

Begum Zaffar Ali, née Sahibzaadi Syeda Fatima, was an Indian women's rights activist and the first woman matriculate of the Indian state of Kashmir and Jammu who went on to become Inspector of Schools in Kashmir. She was an educationist, women's liberation activist, deputy director of education and later a legislator in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. She was associated with the activities of the All India Women's Conference and was its secretary before partition, but a chance meeting with Muhammad Ali Jinnah and his sister, Fatima Jinnah in Kashmir, who would later visit the family for banquets, influenced her and she left the conference to concentrate her efforts in women's liberation movements in the pre-independent India.