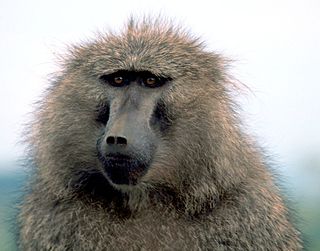

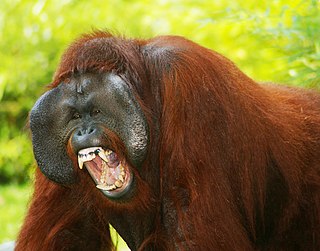

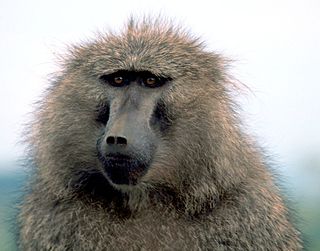

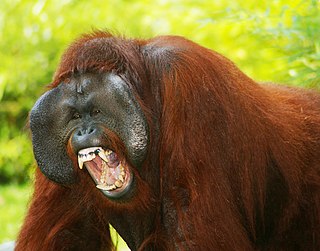

Homininae, also called "African hominids" or "African apes", is a subfamily of Hominidae. It includes two tribes, with their extant as well as extinct species: 1) the tribe Hominini ―and 2) the tribe Gorillini (gorillas). Alternatively, the genus Pan is sometimes considered to belong to its own third tribe, Panini. Homininae comprises all hominids that arose after orangutans split from the line of great apes. The Homininae cladogram has three main branches, which lead to gorillas and to humans and chimpanzees. There are two living species of Panina and two living species of gorillas, but only one extant human species. Traces of extinct Homo species, including Homo floresiensis have been found with dates as recent as 40,000 years ago. Organisms in this subfamily are described as hominine or hominines.

Primatology is the scientific study of non-human primates. It is a diverse discipline at the boundary between mammalogy and anthropology, and researchers can be found in academic departments of anatomy, anthropology, biology, medicine, psychology, veterinary sciences and zoology, as well as in animal sanctuaries, biomedical research facilities, museums and zoos. Primatologists study both living and extinct primates in their natural habitats and in laboratories by conducting field studies and experiments in order to understand aspects of their evolution and behavior.

A social behavior theory which proposes that new behaviors can be acquired by observing and imitating others. Albert Bandura is known for studying this theory. It states that learning is a cognitive process that takes place in a social context and can occur purely through observation or direct instruction, even in the absence of motor reproduction or direct reinforcement. In addition to the observation of behavior, learning also occurs through the observation of rewards and punishments, a process known as vicarious reinforcement. When a particular behavior is rewarded regularly, it will most likely persist; conversely, if a particular behavior is constantly punished, it will most likely desist. The theory expands on traditional behavioral theories, in which behavior is governed solely by reinforcements, by placing emphasis on the important roles of various internal processes in the learning individual.

In psychology, theory of mind refers to the capacity to understand other people by ascribing mental states to them. A theory of mind includes the knowledge that others' beliefs, desires, intentions, emotions, and thoughts may be different from one's own. Possessing a functional theory of mind is crucial for success in everyday human social interactions. People utilize a theory of mind when analyzing, judging, and inferring others' behaviors. The discovery and development of theory of mind primarily came from studies done with animals and infants. Factors including drug and alcohol consumption, language development, cognitive delays, age, and culture can affect a person's capacity to display theory of mind. Having a theory of mind is similar to but not identical with having the capacity for empathy or sympathy.

The origin of language, its relationship with human evolution, and its consequences have been subjects of study for centuries. Scholars wishing to study the origins of language must draw inferences from evidence such as the fossil record, archaeological evidence, contemporary language diversity, studies of language acquisition, and comparisons between human language and systems of animal communication. Many argue that the origins of language probably relate closely to the origins of modern human behavior, but there is little agreement about the facts and implications of this connection.

Research into great ape language has involved teaching chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas and orangutans to communicate with humans and each other using sign language, physical tokens, lexigrams, and imitative human speech. Some primatologists argue that the use of these communication methods indicate primate "language" ability, though this depends on one's definition of language. The cognitive tradeoff hypothesis suggests that human language skills evolved at the expense of the short-term and working memory capabilities observed in other hominids.

Cognitive archaeology is a theoretical perspective in archaeology that focuses on the ancient mind. It is divided into two main groups: evolutionary cognitive archaeology (ECA), which seeks to understand human cognitive evolution from the material record, and ideational cognitive archaeology (ICA), which focuses on the symbolic structures discernable in or inferable from past material culture.

Merlin Wilfred Donald is an emeritus Canadian professor of psychology, neuroanthropology, and cognitive neuroscience, at Case Western Reserve University, and in the Department of Psychology at Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada. He is noted for the position that evolutionary processes need to be considered in determining how the mind deals with symbolic information and language. In particular, he suggests that explicit, algorithmic processes may be inadequate to understanding how the mind works.

The evolution of human intelligence is closely tied to the evolution of the human brain and to the origin of language. The timeline of human evolution spans approximately seven million years, from the separation of the genus Pan until the emergence of behavioral modernity by 50,000 years ago. The first three million years of this timeline concern Sahelanthropus, the following two million concern Australopithecus and the final two million span the history of the genus Homo in the Paleolithic era.

The Hominini form a taxonomic tribe of the subfamily Homininae ("hominines"). Hominini includes the extant genera Homo (humans) and Pan and in standard usage excludes the genus Gorilla (gorillas).

Cognitive specialization suggests that certain behaviors, often in the domain of social communication, are passed on to offspring and refined to be maximally beneficial by the process of natural selection. Specializations serve an adaptive purpose for an organism by allowing the organism to be better suited for its habitat. Over time, specializations often become essential to the species' continued survival. Cognitive specialization in humans has been thought to underlie the acquisition, development, and evolution of language, theory of mind, and specific social skills such as trust and reciprocity. These specializations are considered to be critical to the survival of the species, even though there are successful individuals who lack certain specializations, including those diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder or who lack language abilities. Cognitive specialization is also believed to underlie adaptive behaviors such as self-awareness, navigation, and problem solving skills in several animal species such as chimpanzees and bottlenose dolphins.

There is much to be discovered about the evolution of the brain and the principles that govern it. While much has been discovered, not everything currently known is well understood. The evolution of the brain has appeared to exhibit diverging adaptations within taxonomic classes such as Mammalia and more vastly diverse adaptations across other taxonomic classes. Brain to body size scales allometrically. This means as body size changes, so do other physiological, anatomical, and biochemical constructs connecting the brain to the body. Small bodied mammals have relatively large brains compared to their bodies whereas large mammals have smaller brain to body ratios. If brain weight is plotted against body weight for primates, the regression line of the sample points can indicate the brain power of a primate species. Lemurs for example fall below this line which means that for a primate of equivalent size, a larger brain would be expected. Humans lie well above the line indicating that humans are more encephalized than lemurs. In fact, humans are more encephalized compared to all other primates. This means that human brains have exhibited a larger evolutionary increase in complexity relative to size. Some of these evolutionary changes have been found to be linked to multiple genetic factors, such as proteins and other organelles.

The evolutionary origin of religion and religious behavior is a field of study related to evolutionary psychology, the origin of language and mythology, and cross-cultural comparison of the anthropology of religion. Some subjects of interest include Neolithic religion, evidence for spirituality or cultic behavior in the Upper Paleolithic, and similarities in great ape behavior.

The concept of motor cognition grasps the notion that cognition is embodied in action, and that the motor system participates in what is usually considered as mental processing, including those involved in social interaction. The fundamental unit of the motor cognition paradigm is action, defined as the movements produced to satisfy an intention towards a specific motor goal, or in reaction to a meaningful event in the physical and social environments. Motor cognition takes into account the preparation and production of actions, as well as the processes involved in recognizing, predicting, mimicking, and understanding the behavior of other people. This paradigm has received a great deal of attention and empirical support in recent years from a variety of research domains including embodied cognition, developmental psychology, cognitive neuroscience, and social psychology.

The Hominidae, whose members are known as the great apes or hominids, are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: Pongo ; Gorilla ; Pan ; and Homo, of which only modern humans remain.

Primate cognition is the study of the intellectual and behavioral skills of non-human primates, particularly in the fields of psychology, behavioral biology, primatology, and anthropology.

Deep social mind is a concept in evolutionary psychology; it refers to the distinctively human capacity to 'read' the mental states of others while reciprocally enabling those others to read one's own mental states at the same time. The term 'deep social mind' was first coined in 1999 by Andrew Whiten, professor of Evolutionary and Developmental Psychology at St. Andrews University, Scotland. Together with closely related terms such as 'reflexivity' and 'intersubjectivity', it is now well-established among scholars investigating the evolutionary emergence of human sociality, cognition and communication.

Theory of mind in animals is an extension to non-human animals of the philosophical and psychological concept of theory of mind (ToM), sometimes known as mentalisation or mind-reading. It involves an inquiry into whether non-human animals have the ability to attribute mental states to themselves and others, including recognition that others have mental states that are different from their own. To investigate this issue experimentally, researchers place non-human animals in situations where their resulting behavior can be interpreted as supporting ToM or not.

Social cognitive neuroscience is the scientific study of the biological processes underpinning social cognition. Specifically, it uses the tools of neuroscience to study "the mental mechanisms that create, frame, regulate, and respond to our experience of the social world". Social cognitive neuroscience uses the epistemological foundations of cognitive neuroscience, and is closely related to social neuroscience. Social cognitive neuroscience employs human neuroimaging, typically using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Human brain stimulation techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct-current stimulation are also used. In nonhuman animals, direct electrophysiological recordings and electrical stimulation of single cells and neuronal populations are utilized for investigating lower-level social cognitive processes.

The cognitive tradeoff hypothesis argues that in the cognitive evolution of humans, there was an evolutionary tradeoff between short-term working memory and complex language skills. Specifically, early hominids sacrificed the robust working memory seen in chimpanzees for more complex representations and hierarchical organization used in language. The theory was first brought forth by Japanese primatologist Tetsuro Matsuzawa, a former director of the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University (KUPRI).