Monte Carlo methods

Mathematically

The fundamental theorem of arbitrage-free pricing states that the value of a derivative is equal to the discounted expected value of the derivative payoff where the expectation is taken under the risk-neutral measure [1]. An expectation is, in the language of pure mathematics, simply an integral with respect to the measure. Monte Carlo methods are ideally suited to evaluating difficult integrals (see also Monte Carlo method).

Thus if we suppose that our risk-neutral probability space is and that we have a derivative H that depends on a set of underlying instruments . Then given a sample from the probability space the value of the derivative is . Today's value of the derivative is found by taking the expectation over all possible samples and discounting at the risk-free rate. I.e. the derivative has value:

where is the discount factor corresponding to the risk-free rate to the final maturity date T years into the future.

Now suppose the integral is hard to compute. We can approximate the integral by generating sample paths and then taking an average. Suppose we generate N samples then

which is much easier to compute.

Sample paths for standard models

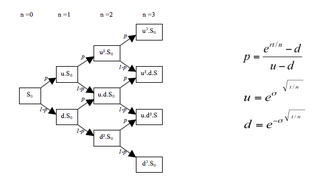

In finance, underlying random variables (such as an underlying stock price) are usually assumed to follow a path that is a function of a Brownian motion 2. For example, in the standard Black–Scholes model, the stock price evolves as

To sample a path following this distribution from time 0 to T, we chop the time interval into M units of length , and approximate the Brownian motion over the interval by a single normal variable of mean 0 and variance . This leads to a sample path of

for each k between 1 and M. Here each is a draw from a standard normal distribution.

Let us suppose that a derivative H pays the average value of S between 0 and T then a sample path corresponds to a set and

We obtain the Monte-Carlo value of this derivative by generating N lots of M normal variables, creating N sample paths and so N values of H, and then taking the average. Commonly the derivative will depend on two or more (possibly correlated) underlyings. The method here can be extended to generate sample paths of several variables, where the normal variables building up the sample paths are appropriately correlated.

It follows from the central limit theorem that quadrupling the number of sample paths approximately halves the error in the simulated price (i.e. the error has order convergence in the sense of standard deviation of the solution).

In practice Monte Carlo methods are used for European-style derivatives involving at least three variables (more direct methods involving numerical integration can usually be used for those problems with only one or two underlyings. See Monte Carlo option model.

Greeks

Estimates for the "Greeks" of an option i.e. the (mathematical) derivatives of option value with respect to input parameters, can be obtained by numerical differentiation. This can be a time-consuming process (an entire Monte Carlo run must be performed for each "bump" or small change in input parameters). Further, taking numerical derivatives tends to emphasize the error (or noise) in the Monte Carlo value – making it necessary to simulate with a large number of sample paths. Practitioners regard these points as a key problem with using Monte Carlo methods.

Variance reduction

Square root convergence is slow, and so using the naive approach described above requires using a very large number of sample paths (1 million, say, for a typical problem) in order to obtain an accurate result. Remember that an estimator for the price of a derivative is a random variable, and in the framework of a risk-management activity, uncertainty on the price of a portfolio of derivatives and/or on its risks can lead to suboptimal risk-management decisions.

This state of affairs can be mitigated by variance reduction techniques.

Antithetic paths

A simple technique is, for every sample path obtained, to take its antithetic path — that is given a path to also take . Since the variables and form an antithetic pair, a large value of one is accompanied by a small value of the other. This suggests that an unusually large or small output computed from the first path may be balanced by the value computed from the antithetic path, resulting in a reduction in variance. [25] Not only does this reduce the number of normal samples to be taken to generate N paths, but also, under same conditions, such as negative correlation between two estimates, reduces the variance of the sample paths, improving the accuracy.

Control variate method

It is also natural to use a control variate. Let us suppose that we wish to obtain the Monte Carlo value of a derivative H, but know the value analytically of a similar derivative I. Then H* = (Value of H according to Monte Carlo) + B*[(Value of I analytically) − (Value of I according to same Monte Carlo paths)] is a better estimate, where B is covar(H,I)/var(H).

The intuition behind that technique, when applied to derivatives, is the following: note that the source of the variance of a derivative will be directly dependent on the risks (e.g. delta, vega) of this derivative. This is because any error on, say, the estimator for the forward value of an underlier, will generate a corresponding error depending on the delta of the derivative with respect to this forward value. The simplest example to demonstrate this consists in comparing the error when pricing an at-the-money call and an at-the-money straddle (i.e. call+put), which has a much lower delta.

Therefore, a standard way of choosing the derivative I consists in choosing a replicating portfolios of options for H. In practice, one will price H without variance reduction, calculate deltas and vegas, and then use a combination of calls and puts that have the same deltas and vegas as control variate.

Importance sampling

Importance sampling consists of simulating the Monte Carlo paths using a different probability distribution (also known as a change of measure) that will give more likelihood for the simulated underlier to be located in the area where the derivative's payoff has the most convexity (for example, close to the strike in the case of a simple option). The simulated payoffs are then not simply averaged as in the case of a simple Monte Carlo, but are first multiplied by the likelihood ratio between the modified probability distribution and the original one (which is obtained by analytical formulas specific for the probability distribution). This will ensure that paths whose probability have been arbitrarily enhanced by the change of probability distribution are weighted with a low weight (this is how the variance gets reduced).

This technique can be particularly useful when calculating risks on a derivative. When calculating the delta using a Monte Carlo method, the most straightforward way is the black-box technique consisting in doing a Monte Carlo on the original market data and another one on the changed market data, and calculate the risk by doing the difference. Instead, the importance sampling method consists in doing a Monte Carlo in an arbitrary reference market data (ideally one in which the variance is as low as possible), and calculate the prices using the weight-changing technique described above. This results in a risk that will be much more stable than the one obtained through the black-box approach.

Quasi-random (low-discrepancy) methods

Instead of generating sample paths randomly, it is possible to systematically (and in fact completely deterministically, despite the "quasi-random" in the name) select points in a probability spaces so as to optimally "fill up" the space. The selection of points is a low-discrepancy sequence such as a Sobol sequence. Taking averages of derivative payoffs at points in a low-discrepancy sequence is often more efficient than taking averages of payoffs at random points.