In Japanese architecture, an engawa or en (縁) is an edging strip of non-tatami-matted flooring, usually wood or bamboo. The ens may run around the rooms, on the outside of the building, in which case they resembles a porch or sunroom.

Nishi Hongan-ji (西本願寺) is a Jōdo Shinshū Buddhist temple in the Shimogyō ward of Kyoto, Japan.

Shinto architecture is the architecture of Japanese Shinto shrines.

Shoin-zukuri (書院造) is a style of Japanese residential architecture used in the mansions of the military, temple guest halls, and Zen abbot's quarters of the Azuchi–Momoyama (1568–1600) and Edo periods (1600–1868). It forms the basis of today's traditional-style Japanese house. Characteristics of the shoin-zukuri development were the incorporation of square posts and floors completely covered with tatami. The style takes its name from the shoin, a term that originally meant a study and a place for lectures on the sūtra within a temple, but which later came to mean just a drawing room or study.

Main hall is the term used in English for the building within a Japanese Buddhist temple compound (garan) which enshrines the main object of veneration. Because the various denominations deliberately use different terms, this single English term translates several Japanese words, among them Butsuden, Butsu-dō, kondō, konpon-chūdō, and hondō. Hondō is its exact Japanese equivalent, while the others are more specialized words used by particular sects or for edifices having a particular structure.

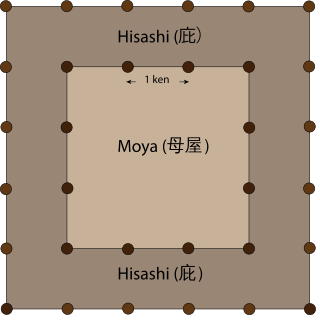

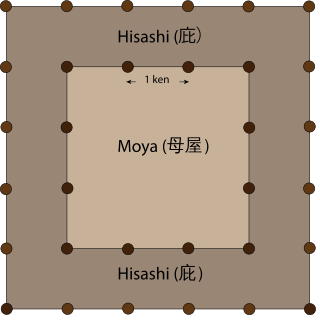

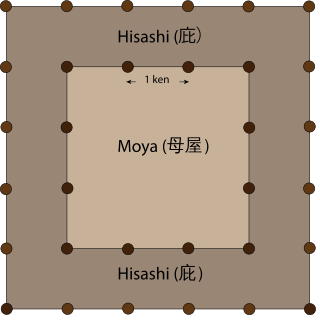

The ken (間) is a traditional Japanese unit of length, equal to six Japanese feet (shaku). The exact value has varied over time and location but has generally been a little shorter than 2 meters. It is now standardized as 1 9⁄11 meter.

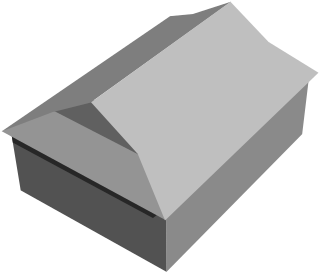

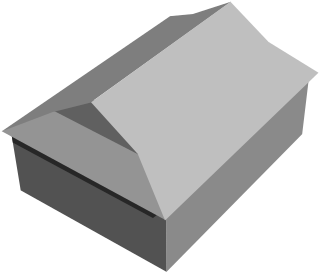

In East Asian architecture, the hip-and-gable roof consists of a hip roof that slopes down on all four sides and integrates a gable on two opposing sides. It is usually constructed with two large sloping roof sections in the front and back respectively, while each of the two sides is usually constructed with a smaller roof section.

The nagare-zukuri or nagare hafu-zukuri is a traditional Shinto shrine architectural style characterized by a very asymmetrical gabled roof projecting outwards on one of the non-gabled sides, above the main entrance, to form a portico. This is the feature which gives it its name. It is the most common style among shrines all over the country. That the building has its main entrance on the side which runs parallel to the roof's ridge makes it belong to the hirairi or hirairi-zukuri (平入・平入造) style.

Hiyoshi-zukuri or hie-zukuri (日吉造), also called shōtei-zukuri / shōtai-zukuri (聖帝造) or sannō-zukuri (山王造) is a rare Shinto shrine architectural style presently found in only three instances, all at Hiyoshi Taisha in Ōtsu, Shiga, hence the name. They are the East and West Honden Hon-gū (本殿本宮) and the Sessha Usa Jingū Honden (摂社宇佐神宮本殿). It is characterized by a hip-and gable roof with verandas called hisashi on the sides. It has a hirairi structure, that is, the building has its main entrance on the side which runs parallel to the roof's ridge.

Ōsaki Hachimangū (大崎八幡宮) is a Shinto shrine in Aoba-ku, Sendai, Miyagi, Japan. The main shrine building has been designated a National Treasure of Japan.

The rōmon is one of two types of two-storied gate used in Japan. Even though it was originally developed by Buddhist architecture, it is now used at both Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines. Its otherwise normal upper story is inaccessible and therefore offers no usable space. It is in this respect similar to the tahōtō and the multi-storied pagoda, neither of which offers, in spite of appearances, usable space beyond the first story. In the past, the name also used to be sometimes applied to double-roof gates.

Zenshūyo is a Japanese Buddhist architectural style derived from Chinese Song Dynasty architecture. Named after the Zen sect of Buddhism which brought it to Japan, it emerged in the late 12th or early 13th century. Together with Wayō and Daibutsuyō, it is one of the three most significant styles developed by Japanese Buddhism on the basis of Chinese models. Until World War II, this style was called karayō but, like the Daibutsuyō style, it was re-christened by Ōta Hirotarō, a 20th-century scholar. Its most typical features are a more or less linear layout of the garan, paneled doors hanging from hinges, intercolumnar tokyō, cusped windows, tail rafters, ornaments called kibana, and decorative pent roofs.

.

Zuiryū-ji (瑞龍寺)) is a Buddhist temple in Takaoka, Toyama Prefecture, Japan. The temple belongs to the Sōtō-school of Japanese Zen Buddhism.

Jōdo-ji (浄土寺) is a temple of Shingon Buddhism in Onomichi, Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan. As a site sacred to the boddhisattva Kannon, it is the 9th temple on the Chūgoku 33 Kannon Pilgrimage. The temple, built at the end of the Kamakura period, is noted for two national treasures: the temple's main hall (hondō) and the treasure pagoda (tahōtō). In addition it holds a number of Important Cultural Property structures and artworks.