Historically, cavalry are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Until the 20th century cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in the roles of reconnaissance, screening, and skirmishing in many armies, or as heavy cavalry for decisive shock attacks in other armies. An individual soldier in the cavalry is known by a number of designations depending on era and tactics, such as a cavalryman, horseman, trooper, cataphract, knight, drabant, hussar, uhlan, mamluk, cuirassier, lancer, dragoon, or horse archer. The designation of cavalry was not usually given to any military forces that used other animals for mounts, such as camels or elephants. Infantry who moved on horseback, but dismounted to fight on foot, were known in the early 17th to the early 18th century as dragoons, a class of mounted infantry which in most armies later evolved into standard cavalry while retaining their historic designation.

A grenadier was historically an assault-specialist soldier who threw hand grenades in siege operation battles. The distinct combat function of the grenadier was established in the mid-17th century, when grenadiers were recruited from among the strongest and largest soldiers. By the 18th century, the grenadier dedicated to throwing hand grenades had become a less necessary specialist, yet in battle, the grenadiers were the physically robust soldiers who led vanguard assaults, such as storming fortifications in the course of siege warfare.

Charles de Batz de Castelmore, also known as d'Artagnan and later Count d'Artagnan, was a French Musketeer who served Louis XIV as captain of the Musketeers of the Guard. He died at the siege of Maastricht in the Franco-Dutch War. A fictionalised account of his life by Gatien de Courtilz de Sandras formed the basis for the d'Artagnan Romances of Alexandre Dumas père, most famously including The Three Musketeers (1844). The heavily fictionalised version of d'Artagnan featured in Dumas' works and their subsequent screen adaptations is now far more widely known than the real historical figure.

The streltsy were the units of Russian firearm infantry from the 16th century to the early 18th century and also a social stratum, from which personnel for streltsy troops were traditionally recruited. They are also collectively known as streletskoye voysko. These infantry troops reinforced feudal levy horsemen or pomestnoye voysko. The first units were established by Ivan the Terrible as part of the first standing army in Russia.

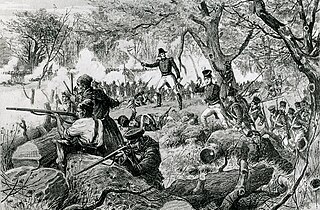

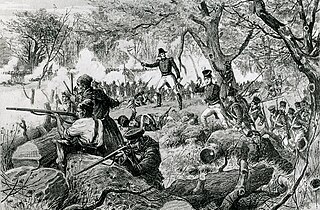

Light infantry refers to certain types of lightly-equipped infantry throughout history. They have a more mobile or fluid function than other types of infantry, such as heavy infantry or line infantry. Historically, light infantry often fought as scouts, raiders, and skirmishers. These are loose formations that fight ahead of the main army to harass, delay, disrupt supply lines, engage the enemy's own skirmishing forces, and generally "soften up" an enemy before the main battle. Light infantrymen were also often responsible for screening the main body of a military formation.

Sepoy, related to sipahi, is a term denoting professional Indian infantryman, traditionally armed with a musket, in the armies of the Mughal Empire and the Maratha Army.

The Troupes coloniales or Armée coloniale, commonly called La Coloniale, were the colonial troops of the French colonial empire from 1900 until 1961. From 1822 to 1900 these troops were designated Troupes de marine, and in 1961 they readopted this name. They were recruited from mainland France and from the French settler as well as indigenous populations of the empire. This force played a substantial role in the conquest of the empire, in World War I, World War II, the First Indochina War and the Algerian War.

Line infantry was the type of infantry that formed the bulk of most European land armies from the mid-17th century to the mid-19th century. Maurice of Nassau and Gustavus Adolphus are generally regarded as its pioneers, while Turenne and Montecuccoli are closely associated with the post-1648 development of linear infantry tactics. For both battle and parade drill, it consisted of two to four ranks of foot soldiers drawn up side by side in rigid alignment, and thereby maximizing the effect of their firepower. By extension, the term came to be applied to the regular regiments "of the line" as opposed to light infantry, skirmishers, militia, support personnel, plus some other special categories of infantry not focused on heavy front line combat.

The Canadian Voltigeurs were a light infantry unit, raised in Lower Canada in 1812, that fought in the War of 1812 between Britain and the United States.

The Musketeers of the military household of the King of France, also known as the Musketeers of the Guard or King's Musketeers, were an elite fighting company of the military branch of the Maison du Roi, the royal household of the French monarchy.

The title of Duc de Lauzun was a French peerage created in 1692 for Antoine Nompar de Caumont under influence of Mary of Modena. All dukes were marshals of France or renowned generals.

The Scottish Guards was a bodyguard unit founded in 1418 by the Valois Charles VII of France, to be personal bodyguards to the French monarchy. They were assimilated into the Maison du Roi and later formed the first company of the Garde du Corps du Roi.

The Régiment d'Agenois was a French infantry regiment formed under the Ancien Régime in 1595. It participated in the American War of Independence.

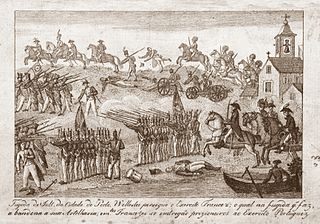

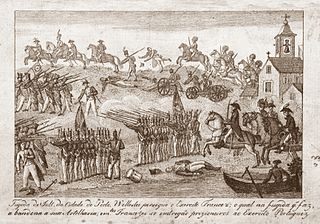

The Walloon Guards were an infantry corps recruited for the Spanish Army in the region now known as Belgium, mainly from Catholic Wallonia. As foreign troops without direct ties amongst the Spanish population, the Walloons were often tasked with the maintenance of public order, eventually being incorporated as a regiment of the Spanish Royal Guard.

The maison militaire du roi de France, in English the military household of the king of France, was the military part of the French royal household or Maison du Roi under the Ancien Régime. The term only appeared in 1671, though such a gathering of units pre-dates this. Like the rest of the royal household, the military household was under the authority of the Secretary of State for the Maison du Roi. Still, it depended on the ordinaire des guerres for its budget. Under Louis XIV, these two officers of state were given joint command of the military household.

Several military units have been known as the Belgian Legion. The term "Belgian Legion" can refer to Belgian volunteers who served in the French Revolutionary Wars, Napoleonic Wars, Revolutions of 1848 and, more commonly, the Mexico Expedition of 1867.

The Anglo-Portuguese Army was the combined British and Portuguese army that participated in the Peninsular War, under the command of Arthur Wellesley. The Army is also referred to as the British-Portuguese Army and, in Portuguese, as the Exército Anglo-Luso or the Exército Anglo-Português.

The 1st Regiment Greek Light Infantry (1810–12) was a light infantry regiment, founded as a local establishment in British service consisting mostly of Greek and Albanian enlisted men and Greek and British officers that served during the Napoleonic Wars. Later it became a regular British Army regiment as the 1st Greek Light Infantry (1812–16). It had no official association with the modern state of Greece or the Filiki Eteria or any Greek War of Independence groups; however, several future leaders of the War of Independence fought in its ranks, as did a number of rank-and-file klephts and armatoloi.

The Legion of Light Troops, also known as the Light Legion or Legion of Alorna was military unit in the Portuguese Army, created in August 1796.

"New order regiments"(Russian: "Полки иноземного строя"), also known in the literature as "foreign formation regiments", were professional military units formed in Russian Tsardom in the 17th century, armed and trained in line with the Western European armies.