A polymer is a substance or material consisting of very large molecules, or macromolecules, composed of many repeating subunits. Due to their broad spectrum of properties, both synthetic and natural polymers play essential and ubiquitous roles in everyday life. Polymers range from familiar synthetic plastics such as polystyrene to natural biopolymers such as DNA and proteins that are fundamental to biological structure and function. Polymers, both natural and synthetic, are created via polymerization of many small molecules, known as monomers. Their consequently large molecular mass, relative to small molecule compounds, produces unique physical properties including toughness, high elasticity, viscoelasticity, and a tendency to form amorphous and semicrystalline structures rather than crystals.

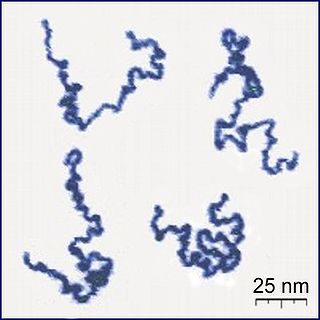

Polymer physics is the field of physics that studies polymers, their fluctuations, mechanical properties, as well as the kinetics of reactions involving degradation and polymerisation of polymers and monomers respectively.

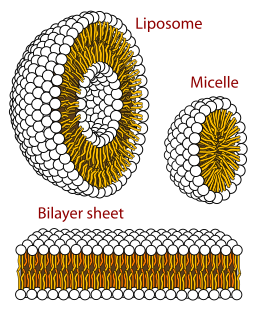

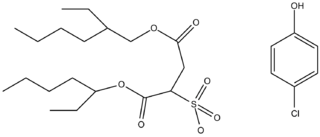

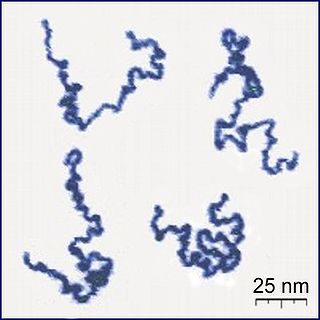

Emulsion polymerization is a type of radical polymerization that usually starts with an emulsion incorporating water, monomer, and surfactant. The most common type of emulsion polymerization is an oil-in-water emulsion, in which droplets of monomer are emulsified in a continuous phase of water. Water-soluble polymers, such as certain polyvinyl alcohols or hydroxyethyl celluloses, can also be used to act as emulsifiers/stabilizers. The name "emulsion polymerization" is a misnomer that arises from a historical misconception. Rather than occurring in emulsion droplets, polymerization takes place in the latex/colloid particles that form spontaneously in the first few minutes of the process. These latex particles are typically 100 nm in size, and are made of many individual polymer chains. The particles are prevented from coagulating with each other because each particle is surrounded by the surfactant ('soap'); the charge on the surfactant repels other particles electrostatically. When water-soluble polymers are used as stabilizers instead of soap, the repulsion between particles arises because these water-soluble polymers form a 'hairy layer' around a particle that repels other particles, because pushing particles together would involve compressing these chains.

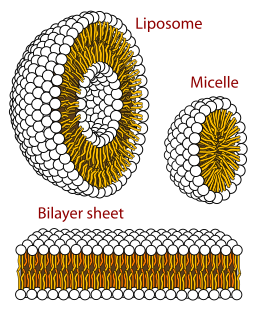

A micelle or micella is an aggregate of surfactant phospholipid molecules dispersed in a liquid, forming a colloidal suspension. A typical micelle in water forms an aggregate with the hydrophilic "head" regions in contact with surrounding solvent, sequestering the hydrophobic single-tail regions in the micelle centre.

Polythiophenes (PTs) are polymerized thiophenes, a sulfur heterocycle. The parent PT is an insoluble colored solid with the formula (C4H2S)n. The rings are linked through the 2- and 5-positions. Poly(alkylthiophene)s have alkyl substituents at the 3- or 4-position(s). They are also colored solids, but tend to be soluble in organic solvents.

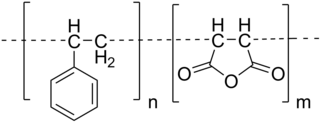

In polymer chemistry, a copolymer is a polymer derived from more than one species of monomer. The polymerization of monomers into copolymers is called copolymerization. Copolymers obtained by copolymerization of two monomer species are sometimes called bipolymers. Those obtained from three and four monomers are called terpolymers and quaterpolymers, respectively.

Step-growth polymerization refers to a type of polymerization mechanism in which bi-functional or multifunctional monomers react to form first dimers, then trimers, longer oligomers and eventually long chain polymers. Many naturally occurring and some synthetic polymers are produced by step-growth polymerization, e.g. polyesters, polyamides, polyurethanes, etc. Due to the nature of the polymerization mechanism, a high extent of reaction is required to achieve high molecular weight. The easiest way to visualize the mechanism of a step-growth polymerization is a group of people reaching out to hold their hands to form a human chain—each person has two hands. There also is the possibility to have more than two reactive sites on a monomer: In this case branched polymers production take place.

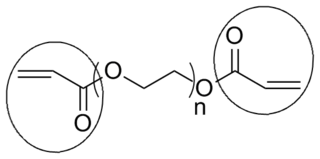

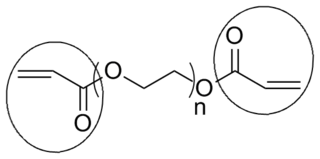

End groups are an important aspect of polymer synthesis and characterization. In polymer chemistry, end groups are functionalities or constitutional units that are at the extremity of a macromolecule or oligomer (IUPAC). In polymer synthesis, like condensation polymerization and free-radical types of polymerization, end-groups are commonly used and can be analyzed for example by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) to determine the average length of the polymer. Other methods for characterization of polymers where end-groups are used are mass spectrometry and vibrational spectrometry, like infrared and Raman spectrometry. Not only are these groups important for the analysis of the polymer, but they are also useful for grafting to and from a polymer chain to create a new copolymer. One example of an end group is in the polymer poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate where the end-groups are circled.

Free-radical polymerization (FRP) is a method of polymerization, by which a polymer forms by the successive addition of free-radical building blocks. Free radicals can be formed by a number of different mechanisms, usually involving separate initiator molecules. Following its generation, the initiating free radical adds (nonradical) monomer units, thereby growing the polymer chain.

Flory–Huggins solution theory is a lattice model of the thermodynamics of polymer solutions which takes account of the great dissimilarity in molecular sizes in adapting the usual expression for the entropy of mixing. The result is an equation for the Gibbs free energy change for mixing a polymer with a solvent. Although it makes simplifying assumptions, it generates useful results for interpreting experiments.

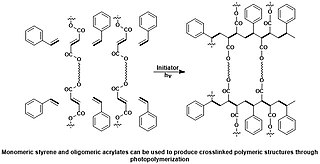

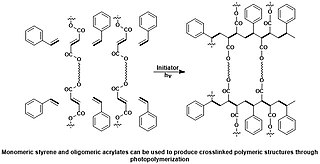

A photopolymer or light-activated resin is a polymer that changes its properties when exposed to light, often in the ultraviolet or visible region of the electromagnetic spectrum. These changes are often manifested structurally, for example hardening of the material occurs as a result of cross-linking when exposed to light. An example is shown below depicting a mixture of monomers, oligomers, and photoinitiators that conform into a hardened polymeric material through a process called curing.

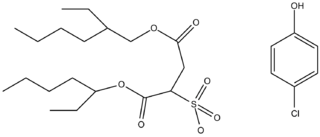

A molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) is a polymer that has been processed using the molecular imprinting technique which leaves cavities in the polymer matrix with an affinity for a chosen "template" molecule. The process usually involves initiating the polymerization of monomers in the presence of a template molecule that is extracted afterwards, leaving behind complementary cavities. These polymers have affinity for the original molecule and have been used in applications such as chemical separations, catalysis, or molecular sensors. Published works on the topic date to the 1930s.

Suspension polymerization is a heterogeneous radical polymerization process that uses mechanical agitation to mix a monomer or mixture of monomers in a liquid phase, such as water, while the monomers polymerize, forming spheres of polymer. The monomer droplets are suspended in the liquid phase. The individual monomer droplets can be considered as undergoing bulk polymerization. The liquid phase outside these droplets help in better conduction of heat and thus tempering the increase in temperature.

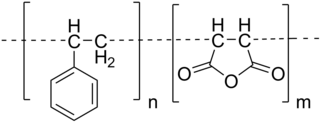

Styrene maleic anhydride is a synthetic polymer that is built-up of styrene and maleic anhydride monomers. The monomers can be almost perfectly alternating, making it an alternating copolymer, but (random) copolymerisation with less than 50% maleic anhydride content is also possible. The polymer is formed by a radical polymerization, using an organic peroxide as the initiator. The main characteristics of SMA copolymer are its transparent appearance, high heat resistance, high dimensional stability, and the specific reactivity of the anhydride groups. The latter feature results in the solubility of SMA in alkaline (water-based) solutions and dispersion.

Bulk polymerization or mass polymerization is carried out by adding a soluble radical initiator to pure monomer in liquid state. The initiator should dissolve in the monomer. The reaction is initiated by heating or exposing to radiation. As the reaction proceeds the mixture becomes more viscous. The reaction is exothermic and a wide range of molecular masses are produced.

In chemistry, cationic polymerization is a type of chain growth polymerization in which a cationic initiator transfers charge to a monomer which then becomes reactive. This reactive monomer goes on to react similarly with other monomers to form a polymer. The types of monomers necessary for cationic polymerization are limited to alkenes with electron-donating substituents and heterocycles. Similar to anionic polymerization reactions, cationic polymerization reactions are very sensitive to the type of solvent used. Specifically, the ability of a solvent to form free ions will dictate the reactivity of the propagating cationic chain. Cationic polymerization is used in the production of polyisobutylene and poly(N-vinylcarbazole) (PVK).

An organogel is a class of gel composed of a liquid organic phase within a three-dimensional, cross-linked network. Organogel networks can form in two ways. The first is classic gel network formation via polymerization. This mechanism converts a precursor solution of monomers with various reactive sites into polymeric chains that grow into a single covalently-linked network. At a critical concentration, the polymeric network becomes large enough so that on the macroscopic scale, the solution starts to exhibit gel-like physical properties: an extensive continuous solid network, no steady-state flow, and solid-like rheological properties. However, organogels that are “low molecular weight gelators” can also be designed to form gels via self-assembly. Secondary forces, such as van der Waals or hydrogen bonding, cause monomers to cluster into a non-covalently bonded network that retains organic solvent, and as the network grows, it exhibits gel-like physical properties. Both gelation mechanisms lead to gels characterized as organogels.

In polymer science, dispersion polymerization is a heterogeneous polymerization process carried out in the presence of a polymeric stabilizer in the reaction medium. Dispersion polymerization is a type of precipitation polymerization, meaning the solvent selected as the reaction medium is a good solvent for the monomer and the initiator, but is a non-solvent for the polymer. As the polymerization reaction proceeds, particles of polymer form, creating a non-homogeneous solution. In dispersion polymerization these particles are the locus of polymerization, with monomer being added to the particle throughout the reaction. In this sense, the mechanism for polymer formation and growth has features similar to that of emulsion polymerization. With typical precipitation polymerization, the continuous phase is the main locus of polymerization, which is the main difference between precipitation and dispersion.

Titanium butoxide is an metal-organic chemical compound with the formula Ti(OBu)4 (Bu = CH2CH2CH2CH3). It is a colorless odorless liquid, although aged samples are yellowish with a weak alcohol-like odor. It is soluble in many organic solvents. It hydrolyzes to give titanium dioxide, which allows deposition of TiO2 coatings of various shapes and sizes down to the nanoscale.

Cardo polymers are a sub group of polymers where carbons in the backbone of the polymer chain are also incorporated into ring structures. These backbone carbons are quaternary centers. As such, the cyclic side group lies perpendicular to the plane of the polymer chain, creating a looping structure. These rings are bulky structures which sterically hinder the polymers and prevent them from packing tightly. They also restrict the rotational range of motion of the polymer chain, creating a rigid backbone. As a result of their unique structures, these polymers have notably high thermal stability and solubility. There have been recent advances made in the applications of cardo polymers to membranes used for gas separation and transport.