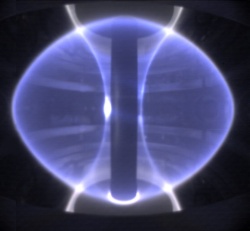

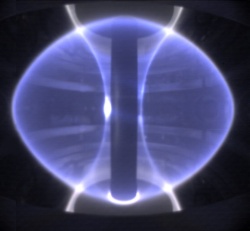

A tokamak is a device which uses a powerful magnetic field generated by external magnets to confine plasma in the shape of an axially symmetrical torus. The tokamak is one of several types of magnetic confinement devices being developed to produce controlled thermonuclear fusion power. The tokamak concept is currently one of the leading candidates for a practical fusion reactor.

Igor Yevgenyevich Tamm was a Soviet physicist who received the 1958 Nobel Prize in Physics, jointly with Pavel Alekseyevich Cherenkov and Ilya Mikhailovich Frank, for their 1934 discovery and demonstration of Cherenkov radiation. He also predicted the quasi-particle of sound: the phonon; and in 1951, together with Andrei Sakharov, proposed the Tokamak system.

This timeline of nuclear fusion is an incomplete chronological summary of significant events in the study and use of nuclear fusion.

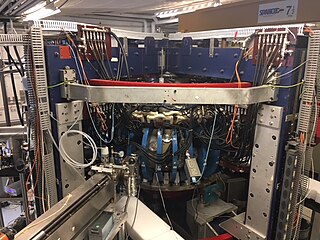

The T-15 is a Russian nuclear fusion research reactor located at the Kurchatov Institute, which is based on the (Soviet-invented) tokamak design. It was the first industrial prototype fusion reactor to use superconducting magnets to control the plasma. These enormous superconducting magnets confined the plasma the reactor produced, but failed to sustain it for more than just a few seconds. Despite not being immediately applicable, this new technological advancement proved to the USSR that they were on the right path. In the original shape, a toroidal chamber design, it had a major radius of 2.43 m and minor radius 0.7 m.

Magnetic confinement fusion (MCF) is an approach to generate thermonuclear fusion power that uses magnetic fields to confine fusion fuel in the form of a plasma. Magnetic confinement is one of two major branches of controlled fusion research, along with inertial confinement fusion.

ZETA, short for Zero Energy Thermonuclear Assembly, was a major experiment in the early history of fusion power research. Based on the pinch plasma confinement technique, and built at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment in the United Kingdom, ZETA was larger and more powerful than any fusion machine in the world at that time. Its goal was to produce large numbers of fusion reactions, although it was not large enough to produce net energy.

Evgeny Pavlovich Velikhov is a physicist and scientific leader in the Russian Federation. His scientific interests include plasma physics, lasers, controlled nuclear fusion, power engineering, and magnetohydrodynamics. He is the author of over 1500 scientific publications and a number of inventions and discoveries.

Oleg Alexandrovich Lavrentiev was a physicist who worked on the Soviet atomic bomb project and whose research contributions were fundamental to the understanding of thermonuclear fusion.

Vitaly Dmitrievich Shafranov was a Russian theoretical physicist and Academician who worked with plasma physics and thermonuclear fusion research.

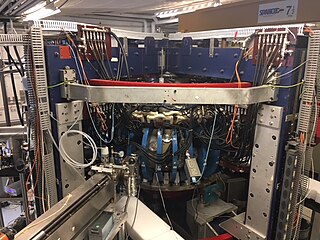

The Hybrid Illinois Device for Research and Applications (HIDRA) is a medium-sized toroidal magnetic fusion device housed in the Nuclear Radiation Laboratory and operated by the Center for Plasma-Material Interactions (CPMI) within the Department of Nuclear, Plasma and Radiological Engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, United States. HIDRA had its first plasma at the end of April 2016 and started experimental campaigns by December of that year. HIDRA is the former WEGA classical stellarator that was operated at the Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics in Greifswald Germany from 2001 to 2013.

The Princeton Large Torus, was an early tokamak built at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL). It was one of the first large scale tokamak machines and among the most powerful in terms of current and magnetic fields. Originally built to demonstrate that larger devices would have better confinement times, it was later modified to perform heating of the plasma fuel, a requirement of any practical fusion power device.

Uragan-2M is a stellarator installed at the Institute of Plasma Physics National Science Center, which is part of the Kharkiv Institute of Physics and Technology in Kharkiv, Ukraine. It was the largest stellarator (torsatron) in Europe until the construction of Wendelstein 7-X.

Ksenia Aleksandrovna Razumova is a Russian physicist. She graduated from the Physical Faculty of Moscow University in 1955 and took a position at the then called Kurchatov Institute of Atomic Energy in Moscow, then USSR. She defended her Ph.D. in 1966, was Candidate in Physical and Mathematical sciences in 1967, and became Doctor of Sciences in 1984. She is laboratory head at the Institute of Nuclear Fusion, Russian Research Centre Kurchatov Institute. Since the beginning she is actively involved plasma physics in research on the tokamak line of Magnetic confinement fusion.

Yuri Aleksandrovich Romanov was a Russian physicist who spent his career in the former Soviet program of nuclear weapons.

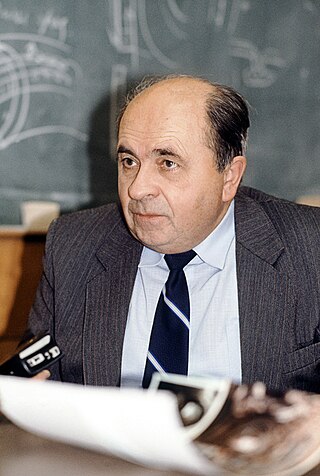

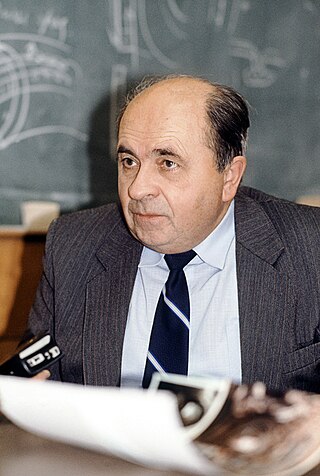

Boris Borisovich Kadomtsev was a Soviet and Russian plasma physicist who worked on controlled fusion problems. He developed a theory of transport phenomena in turbulent plasmas and a theory of the so-called anomalous behavior of plasmas in magnetic fields. In 1966, he discovered plasma instability with trapped particles.

Jürgen Nührenberg is a German plasma physicist.

The history of nuclear fusion began early in the 20th century as an inquiry into how stars powered themselves and expanded to incorporate a broad inquiry into the nature of matter and energy, as potential applications expanded to include warfare, energy production and rocket propulsion.

Theta-pinch, or θ-pinch, is a type of fusion power reactor design. The name refers to the configuration of currents used to confine the plasma fuel in the reactor, arranged to run around a cylinder in the direction normally denoted as theta in polar coordinate diagrams. The name was chosen to differentiate it from machines based on the pinch effect that arranged their currents running down the centre of the cylinder; these became known as z-pinch machines, referring to the Z-axis in cartesian coordinates.

Igor Nikolaevich Golovin was a Russian physicist whose career was spent on the former Soviet program of nuclear weapons and nuclear fusion. He is known for coining the term Tokamak.