Related Research Articles

The Indische Partij (IP) or Indies Party was a short-lived but influential political organisation founded in 1912 by the Indo-European (Eurasian) journalist E.F.E. Douwes Dekker and the Javanese physicians Tjipto Mangoenkoesoemo and Soewardi Soerjaningrat. As one of the first political organisations pioneering Indonesian nationalism in the colonial Dutch East Indies it inspired several later organisations such as the Nationaal Indische Party (N.I.P.) or Sarekat Hindia in 1919 and Indo Europeesch Verbond (I.E.V.) in 1919. Its direct successor was Insulinde.

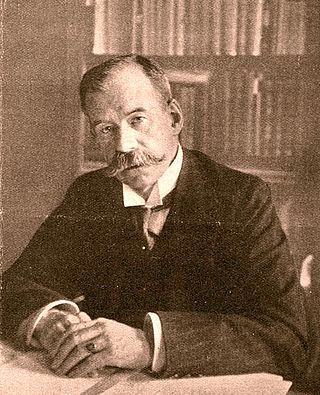

Conrad Theodor "Coen" van Deventer was a Dutch lawyer, an author about the Dutch East Indies and a member of parliament of the Netherlands. He became known as the spokesman of the Dutch Ethical Policy Movement. He lived at Surinamestraat 20, The Hague (1903–1915), former residence of John Ricus Couperus, his son writer Louis Couperus and the rest of his family (1884–1902).

Suharso, (1912–1971) also spelled Soeharso, was an Indonesian medical doctor known for his work with disabled people and in the rehabilitation of people injured during the Indonesian National Revolution. He was declared to be a National Hero of Indonesia in 1973.

Djawa Tengah was a major Malay-language peranakan Chinese daily newspaper in Semarang, Dutch East Indies from 1909 to 1938. It is said to have been the first Chinese newspaper in Semarang.

De Preangerbode was a Dutch language newspaper published in Bandung, Preanger Regencies Residency, Dutch East Indies from 1896 to 1957. After 1923 it was renamed Algemeen Indisch Dagblad de Preangerbode.

Neratja, later Hindia Baroe, was a Malay language newspaper printed from 1917 to 1926 in Weltevreden, Dutch East Indies. Although originally founded with government support to be a Malay voice for the Dutch Ethical Policy, before long it became associated with the Sarekat Islam and the Indonesian National Awakening. Among its editors were important figures of the Indonesian national movement such as Abdul Muis and Agus Salim.

Djawi-Hisworo was a newspaper printed in Surakarta, Dutch East Indies from 1909 to 1919 in Malay and Javanese. It was considered the mouthpiece of the early Javanese self-improvement organization Boedi Oetomo.

Algemeen handelsblad voor Nederlandsch-Indië was a Dutch language newspaper, published from 1924 to 1942 in Semarang, Dutch East Indies.

Evert Jansen was a newspaper editor, journalist and politician from the Dutch East Indies. From the 1910s to the 1940s, he was editor of a number of major papers including De Locomotief, Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, Algemeen handelsblad voor Nederlandsch-Indië, and De Indische Courant.

Adolf Baars was a Dutch-Jewish Communist, engineer, and writer who is largely remembered today for his early role in the Indische Sociaal-Democratische Vereeniging and the Indonesian Communist Party.

George Antoon Philip Weijer (1891-1979) was a business representative in colonial Indonesia, an economics professor at the University of Utrecht, and a government advisor and company director in the Netherlands.

Warna Warta was a Malay language Peranakan Chinese newspaper published in Semarang, Dutch East Indies from 1902 to 1933. Alongside its more popular rival Djawa Tengah, it was highly influential among the Chinese Indonesian population of Semarang during this time.

The Indonesian Fascist Party was a short-lived Fascist political party founded in Bandung, Dutch East Indies in the summer of 1933 by a Javanese economist and politician named Notonindito. Although it did not last long and is poorly documented, it is often cited as an example of how European Fascist ideas could manifest themselves in an Asian context, as well as appearing in conspiracy literature exaggerating its importance.

Saadah Alim (1897–1968) was a writer, playwright, translator, journalist and educator in the Dutch East Indies and in Indonesia after independence. She was one of only a handful of Indonesian women authors to be published during the colonial period, alongside Fatimah Hasan Delais, Sariamin Ismail, Soewarsih Djojopoespito and a few others. She is known primarily for her journalism, her collection of short stories Taman Penghibur Hati (1941), and her comedic play Pembalasannya (1940).

Soetitah was a Sarekat Islam and Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) propagandist, activist, and schoolteacher in Semarang, Dutch East Indies in the 1910s and 1920s. She was a close ally of Semaun, Tan Malaka, and other Semarang communists of the time and was chair of the women's section of the party in the early 1920s. She was exiled by the Dutch to the Boven-Digoel concentration camp from 1927 to 1930.

Louis Johan Alexander Schoonheyt (1903-1986), commonly known as L. J. A. Schoonheyt, was a Dutch medical doctor, writer, and supporter of the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands before World War II. From 1935 to 1936 he was the camp doctor at the Boven-Digoel concentration camp in New Guinea, Dutch East Indies, and is mostly known today for the book he wrote about his experiences there, Boven-Digoel: Het land van communisten en kannibalen (1936). His praise for the conditions in the camp earned him the ire of the internees, Indonesian nationalists, and Dutch human rights advocates; E. du Perron called him a 'colonial bandit', while many internees burned his book after reading it in the camp.

Soekaesih was a Communist Party of Indonesia activist known for being one of only a handful of female political prisoners exiled by the Netherlands government to Boven-Digoel concentration camp. After being released she traveled to the Netherlands in the late 1930s and campaigned for the camp to be shut down.

Phoa Tjoen Hoat, who also published under the name Th. H. Phoa Sr., was a Chinese Indonesian, Malay language journalist, translator and newspaper editor active in the Dutch East Indies in the early twentieth century.

Abdul Rasjid Siregar gelar Mangaradja Mahkota Soeangkoepon, commonly known as Dr. Abdul Rasjid, was a politician and physician in the Dutch East Indies. He was elected or appointed to the Volksraad from 1931 to 1942, during which time he sat with the Indonesian nationalist faction. During the 1930s, he became convinced that public health and cooperation with traditional healers should be central to the mission of physicians in the Indies.

Kho Tjoen Wan, sometimes spelled Kho Tjoen Gwan, was a Chinese Indonesian journalist, writer and political activist active mainly from the 1910s to the 1930s in the Dutch East Indies. He was involved with the Communist Party of Indonesia in the 1920s and may have been its first ethnically Chinese executive member.

References

- ↑ "Daftar Nama" (PDF) (in Indonesian). Perpustakaan Nasional RI. 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- 1 2 "De moord op den ondervoorzitter van den Kedirischen Landraad". De Locomotief (in Dutch). 1927-03-04.

- 1 2 "BINNENLAND. Vier repatrieerende Javaansche juristen". De Indische courant (in Dutch). 1925-09-16.

- ↑ "Aryanti (1928-...)". Data Pokok Kebahasaan dan Kesastraan (in Indonesian). Badan Pengembangan dan Pembinaan Bahasa. 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ↑ "Een nieuw Studiefonds". Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad (in Dutch). 1921-10-21.

- ↑ "Passagierslijst". Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië (in Dutch). 1921-10-25.

- ↑ Poeze, Harry; van Dijk, Cees; van der Meulen, Inge (1986). In Het Land Van De Overheerser: I: Indonesiërs in Nederland 1600-1950 (in Dutch). Brill. p. 166.

- ↑ "Examen-Mercurius". Haagsche courant (in Dutch). 1923-02-01.

- ↑ "Een Javaan te Berlijn Gepromoveerd". Algemeen handelsblad voor Nederlandsch-Indië (in Dutch). 1924-05-11.

- ↑ "Ontevredenheid in Chineesche hendelskringen te Tegal". De Locomotief (in Dutch). 1925-11-25.

- ↑ "Boedi Oetomo". De Locomotief (in Dutch). 1926-07-17.

- ↑ "De R.P. Notonindito". De Locomotief (in Dutch). 1926-07-20.

- ↑ "Pekalongan". De Indische courant (in Dutch). 1926-11-09.

- ↑ "PEKALONGAN - Raadscommissies". De Locomotief (in Dutch). 1926-08-25.

- ↑ "Het P.S.I.-Congres". De Locomotief (in Dutch). 1927-10-01.

- ↑ "Het P.S.I.-Congres". De Locomotief (in Dutch). 1927-10-03.

- ↑ "De P.D.I." De Indische courant (in Dutch). 1928-01-09.

- ↑ "De Indonesische Handelsvereeniging Pekalongan". Algemeen handelsblad voor Nederlandsch-Indië (in Dutch). 1928-10-26.

- ↑ "PEKALONGAN Verkiezing Gemeenteraad". De Locomotief (in Dutch). 1928-05-21.

- ↑ Voornaamste voorschriften en personalia betreffende de decentralisatie en de bestuurshervorming, alsmede de Grondwet en de Indische staatsregeling (in Dutch). Batavia (Dutch East Indies): Landsdrukkerij. 1931. p. 226.

- ↑ "Een protestvergadering der P. S. I." Algemeen handelsblad voor Nederlandsch-Indië (in Dutch). 1929-04-29.

- 1 2 3 "De inheemsche Fascisten. Thans onderwerping, doch in de toekomst vrijheid. Het program van de Partij Fascist Indonesia". De Locomotief (in Dutch). 1933-07-24.

- 1 2 "Een Inheemsche "Nifo". Notonindito richt Partij Fascist Indonesia op". De Locomotief (in Dutch). 1933-07-22.

- ↑ "Parindra's loyal cadres. Fascism and anticolonial nationalism in late colonial Indonesia, 1935-1942". International Institute for Asian Studies. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ↑ Hartanto, Agung Dwi (2007). Seabad pers kebangsaan, 1907-2007 (1 ed.). Jakarta: I:Boekoe. p. 439. ISBN 9789791436021.

- ↑ "DE VOLKSBEWEGING". Overzicht van de Inlandsche en Maleisisch-Chineesche pers (31): 484–5. 1933-08-05.

- ↑ "Notonindito en de Inheemsche Fascisten". De Locomotief (in Dutch). 1933-07-31.

- ↑ "De Partai Fascis Indonesia". De Indische courant (in Dutch). 1933-07-31.

- ↑ "Japan". Overzicht van de Inlandsche en Maleisisch-Chineesche pers (in Dutch) (48): 764. 1933-12-02.

- ↑ Wirasmo Notonindito, R. P. (1946). "Pengantar peladjaran ekonomi". Onesearch. A.C. Nix & Co. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ↑ "G.I.M. - EN B.P.I. - LEDEN GEARRESTEERD". Algemeen Indisch dagblad (in Dutch). 1947-07-05.

- ↑ "Advertisement. Soenario-Concern". Algemeen Indisch dagblad (in Dutch). 1947-05-03.

- ↑ "Naar het voorbeeld van NIVA Indonesische accountants verenigen zich". Algemeen Indisch dagblad : de Preangerbode (in Dutch). 1952-10-02.

- ↑ "Economische Academie". Algemeen Indisch dagblad : de Preangerbode (in Dutch). 1956-11-22.