Dissolution

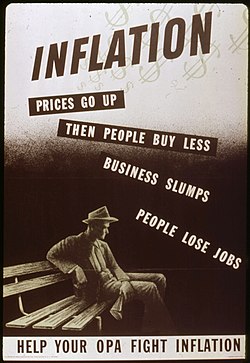

As early as 1944, in its annual debate about price control extension, Congress discussed limiting the power of the OPA as World War II drew to a close and the necessity of price controls was called into question. While some argued for the continuation of price controls to hold post war inflation in check, there was widespread support among conservatives and businessmen for the rapid deregulation of the economy as it reconverted to a civilian footing. [6] Groups such as the National Association of Manufacturers and the National Retail Dry Good Association sought to guarantee companies a minimum amount of profits, thereby effectively limiting the price control measures. [7] However, the OPA still enjoyed widespread popular support and the agency was renewed in 1944 and again in 1945. [7] [8] While these renewals were considerable successes for many consumer advocacy groups, they also marked the height of the OPA, from which the agency's power and popularity would decline in the next two years. [7]

By June 1946, significant opposition by NAM and NRDA had been mounted to sway Congress, which, only two days before the existing legislation was set to expire, passed a bill that would have left the OPA a much-weakened version of its past self. [7] [8] President Harry S. Truman vetoed this bill in hopes of forcing Congress to create a stronger one, but as the month of June came to an end, the OPA shut down, and its price and rent controls went with it. [8] The result was a sharp jump in prices, with food increasing by 14 percent and the cost of overall living rising by 6 percent, an equivalent to more than 100 percent per year. [7] [8] Consumers all over the nation turned out in varying numbers to protest these increases, with labor unions forming a major part of the participants. [7] [8]

By the end of July, Congress had reversed course and passed legislation reinstating the OPA and price controls, though this bill was no stronger than what President Truman had vetoed earlier. [7] [8] This much-weakened version of the OPA did not last long, as meat packers launched their own form of protest against the agency, slowing slaughtering rates and withholding meat from market. [7] [8] The resulting widespread shortages did much to damage the public faith in the OPA, which was now seen as ineffective, and the Democrat-led Congress. [7] [8] When faced with the choices of higher prices or no meat, the consumers chose the latter. Although President Truman ended price controls on meat, on October 14, just two weeks before the election, in a rejection of price controls and as a sign of the changing attitude of the American public towards a control-free re-conversion, many Democratic incumbents were defeated, and Republicans gained control of Congress. [6] [7] [8] Following this defeat, Truman lifted almost all price and wage controls and, while the OPA was authorized to exist through June 30, 1947, its range of tasks and ability to effectively regulate prices was curtailed severely, being reduced to rent control and some price control over a very limited number of goods. [8] Most functions of the OPA were transferred to the newly established Office of Temporary Controls (OTC) by Executive Order 9809, December 12, 1946. The Financial Reporting Division was transferred to the Federal Trade Commission. By the end of December 1946, many of OPA's local offices and price boards were closed, and the OPA did not survive until its authorized June 30 extension. [8]

The OPA was abolished effective May 29, 1947 by the General Liquidation Order, issued March 14, 1947, by the OPA Administrator. [9] Some of its functions were taken up by successor agencies:

- Sugar and sugar products distribution by the Sugar Rationing Administration in the Department of Agriculture pursuant to the Sugar Control Extension Act (61 Stat. 36), March 31, 1947

- Price controls over rice by the Department of Agriculture by Executive Order 9841, on April 23, 1947, effective May 4, 1947

- Food subsidies by the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, effective May 4, 1947

- Rent control by the Office of the Housing Expediter, effective May 4, 1947

- Price violation litigation by the Department of Justice, effective June 1, 1947

- All other OPA functions by the Division of Liquidation, Department of Commerce, effective June 1, 1947.

Famous employees include economist John Kenneth Galbraith, legal scholar William Prosser, President Richard Nixon, and law professor John Honnold. [7]

The OPA is featured, in fictionalized form as the Bureau of Price Regulation, in Rex Stout's Nero Wolfe mystery novel The Silent Speaker .

The OPA unsuccessfully tried to revoke the car dealer license of unorthodox businessman Madman Muntz for violating used car regulations, subject to price control. Muntz was acquitted in Los Angeles Superior Court on 1 August 1945. [10]

During the Korean War, similar functions were performed by the Office of Price Stabilization (OPS).