John Ray FRS was a Christian English naturalist widely regarded as one of the earliest of the English parson-naturalists. Until 1670, he wrote his name as John Wray. From then on, he used 'Ray', after "having ascertained that such had been the practice of his family before him". He published important works on botany, zoology, and natural theology. His classification of plants in his Historia Plantarum, was an important step towards modern taxonomy. Ray rejected the system of dichotomous division by which species were classified by repeated sub-division into groups according to a pre-conceived series of characteristics they have or have not, and instead classified plants according to similarities and differences that emerged from observation. He was among the first to attempt a biological definition for the concept of species, as "a group of morphologically similar organisms arising from a common ancestor". Another significant contribution to taxonomy was his division of plants into those with two seedling leaves (dicotyledons) or only one (monocotyledons), a division used in taxonomy today.

The European honey buzzard, also known as the pern or common pern, is a bird of prey in the family Accipitridae.

The cirl bunting, , is a passerine bird in the bunting family Emberizidae, a group now separated by most modern authors from the finches, Fringillidae.

Harry Forbes Witherby, MBE, FZS, MBOU was a noted British ornithologist, author, publisher and founding editor of the magazine British Birds.

Thomas Pennant was a Welsh naturalist, traveller, writer and antiquarian. He was born and lived his whole life at his family estate, Downing Hall, near Whitford, Flintshire, in Wales.

Francis Willughby FRS was an English ornithologist, ichthyologist and mathematician, and an early student of linguistics and games.

William Swainson FLS, FRS, was an English ornithologist, malacologist, conchologist, entomologist, and artist. A prolific collector of natural history specimens he produced an influential illustrated classification of birds based on the quinarian system that was then in fashion. He settled in New Zealand in later life.

George Montagu was a British military officer and ornithologist. He was known for his pioneering Ornithological Dictionary of 1802, which for the first time accurately defined the status of Britain's birds. He is remembered today for species such as the Montagu's harrier, named after him.

John Latham was an English physician, naturalist and author. His main works were A General Synopsis of Birds (1781–1801) and A General History of Birds (1821–1828). He was able to examine specimens of Australian birds that reached England in the final twenty years of the 18th century, and was responsible for providing English names for many of them. He named some of Australia's most famous birds, including the emu, sulphur-crested cockatoo, wedge-tailed eagle, superb lyrebird, Australian magpie, magpie-lark, white-throated needletail and pheasant coucal. Latham has been called the "grandfather" of Australian ornithology. He was also the first to describe the hyacinth macaw from South America.

Sir William Jardine, 7th Baronet of Applegarth FRS FRSE FLS FSA was a Scottish naturalist. He is known for his editing of a long series of natural history books, The Naturalist's Library.

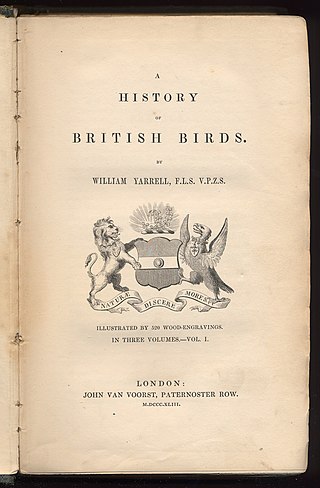

William Yarrell was an English zoologist, prolific writer, bookseller and naturalist admired by his contemporaries for his precise scientific work.

Nature writing is nonfiction or fiction prose about the natural environment. It often draws heavily from scientific information and facts while also incorporating philosophical reflection upon various aspects of nature. Works are frequently written in the first person and include personal observations.

The ground woodpecker is one of only three ground-dwelling woodpeckers in the world. It inhabits rather barren, steep, boulder-strewn slopes in relatively cool hilly and mountainous areas of South Africa, Lesotho and Eswatini and has yet to be recorded outside of Southern Africa. It is found in a broad swath running from southwest to northeast, from the Cape Peninsula and Namaqualand to Mpumalanga. It is closely related to the woodpeckers of the genus Campethera, some of which also employ terrestrial foraging strategies.

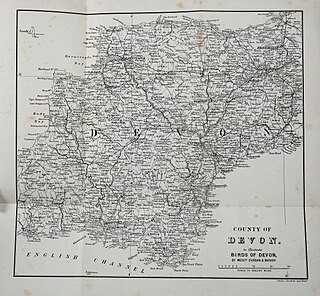

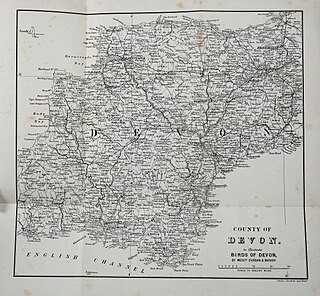

Devon Birds, known as the Devon Bird Watching & Preservation Society from its founding in 1928 until it was renamed in 2005, is one of the UK's regional ornithological societies.

Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots is an 1832 book containing 42 hand-coloured lithographs by Edward Lear. He produced 175 copies for sale to subscribers as a part-publication, which were later bound as a book. Lear started painting parrots in 1830 when he was 18 years old, and to get material for his book he studied live birds at the London Zoo and in private collections. The latter included those of Edward Smith Stanley, later 13th Earl of Derby, who had a large menagerie at Knowsley Hall, and Benjamin Leadbeater, a taxidermist and trader in specimens. Lear drew onto lithographic plates for printing by Charles Joseph Hullmandel, who was known for the quality of his reproductions of fine art.

A History of British Birds is a natural history book by Thomas Bewick, published in two volumes. Volume 1, Land Birds, appeared in 1797. Volume 2, Water Birds, appeared in 1804. A supplement was published in 1821. The text in Land Birds was written by Ralph Beilby, while Bewick took over the text for the second volume. The book is admired mainly for the beauty and clarity of Bewick's wood-engravings, which are widely considered his finest work, and among the finest in that medium.

William Yarrell's A History of British Birds was first published as a whole in three volumes in 1843, having been serialised, three sheets every two months, over the previous six years. It is not a history of ornithology but a natural history, a handbook or field guide systematically describing every species of bird known to occur in Britain. A separate article of about six pages, containing an image, a description, and an account of worldwide distribution, together with reports of behaviour, is provided for each species.

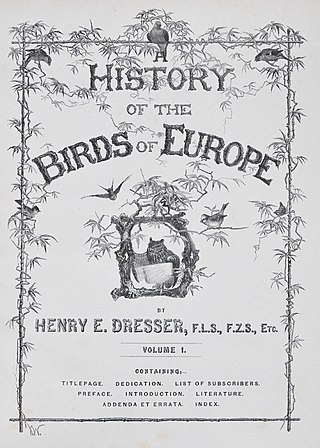

A History of the Birds of Europe, Including all the Species Inhabiting the Western Palearctic Region is a nine-volume ornithological book published in parts between 1871 and 1896. It was mainly written by Henry Eeles Dresser, although Richard Bowdler Sharpe co-authored the earlier volumes. It describes all the bird species reliably recorded in the wild in Europe and adjacent geographical areas with similar fauna, giving their worldwide distribution, variations in appearance and migratory movements.

Charles Swainson (1840–1913) M.A. was an English cleric and naturalist. He was rector of High Hurst Wood, Sussex, from 1872 to 1874, from where he published his Handbook of Weather Folk-Lore which also included folklore and mythology relating to elements of nature and a short chapter on birds.

The Wonderful Mr Willughby: The First True Ornithologist is a 2018 biography, written by Tim Birkhead, about Francis Willughby (1635–1672), an English ornithologist, ichthyologist, entomologist, and Fellow of the Royal Society. Birkhead's work is the first book-length biography of Willughby.