Ethology is a branch of zoology that studies the behaviour of non-human animals. It has its scientific roots in the work of Charles Darwin and of American and German ornithologists of the late 19th and early 20th century, including Charles O. Whitman, Oskar Heinroth, and Wallace Craig. The modern discipline of ethology is generally considered to have begun during the 1930s with the work of the Dutch biologist Nikolaas Tinbergen and the Austrian biologists Konrad Lorenz and Karl von Frisch, the three winners of the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Ethology combines laboratory and field science, with a strong relation to neuroanatomy, ecology, and evolutionary biology.

Konrad Zacharias Lorenz was an Austrian zoologist, ethologist, and ornithologist. He shared the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Nikolaas Tinbergen and Karl von Frisch. He is often regarded as one of the founders of modern ethology, the study of animal behavior. He developed an approach that began with an earlier generation, including his teacher Oskar Heinroth.

Erich Seligmann Fromm was a German-American social psychologist, psychoanalyst, sociologist, humanistic philosopher, and democratic socialist. He was a German Jew who fled the Nazi regime and settled in the United States. He was one of the founders of The William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry, Psychoanalysis and Psychology in New York City and was associated with the Frankfurt School of critical theory.

Nikolaas "Niko" Tinbergen was a Dutch biologist and ornithologist who shared the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Karl von Frisch and Konrad Lorenz for their discoveries concerning the organization and elicitation of individual and social behavior patterns in animals. He is regarded as one of the founders of modern ethology, the study of animal behavior.

Instinct is the inherent inclination of a living organism towards a particular complex behaviour, containing innate (inborn) elements. The simplest example of an instinctive behaviour is a fixed action pattern (FAP), in which a very short to medium length sequence of actions, without variation, are carried out in response to a corresponding clearly defined stimulus.

Group selection is a proposed mechanism of evolution in which natural selection acts at the level of the group, instead of at the level of the individual or gene.

Douglas Alexander Spalding was a British biologist who studied animal behaviour and worked in the home of Viscount Amberley.

Robert Ardrey was an American playwright, screenwriter and science writer perhaps best known for The Territorial Imperative (1966). After a Broadway and Hollywood career, he returned to his academic training in anthropology in the 1950s.

The killer ape theory or killer ape hypothesis is the theory that war and interpersonal aggression was the driving force behind human evolution. It was originated by Raymond Dart in the 1950s; it was developed further in African Genesis by Robert Ardrey in 1961.

Homo Necans: The Anthropology of Ancient Greek Sacrificial Ritual and Myth is a 1972 book on ancient Greek religion and mythology by the classicist Walter Burkert. It won the Weaver Award for Scholarly Literature, awarded by the Ingersoll Foundation, in 1992.

Wolfgang Wickler was a German zoologist, behavioral researcher and author. He led the ethological department of the Max Planck Institute for Behavioral Physiology from 1974, and he took over as director of the institute in 1975. Even after he was given emeritus status, he remained closely associated to the institute in Seewiesen and ensured its smooth transition under the newly created Max Planck Institute for Ornithology.

Human ethology is the study of human behavior. Ethology as a discipline is generally thought of as a sub-category of biology, though psychological theories have been developed based on ethological ideas. The bridging between biological sciences and social sciences creates an understanding of human ethology. The International Society for Human Ethology is dedicated to advancing the study and understanding of human ethology.

The history of evolutionary psychology began with Charles Darwin, who said that humans have social instincts that evolved by natural selection. Darwin's work inspired later psychologists such as William James and Sigmund Freud but for most of the 20th century psychologists focused more on behaviorism and proximate explanations for human behavior. E. O. Wilson's landmark 1975 book, Sociobiology, synthesized recent theoretical advances in evolutionary theory to explain social behavior in animals, including humans. Jerome Barkow, Leda Cosmides and John Tooby popularized the term "evolutionary psychology" in their 1992 book The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and The Generation of Culture. Like sociobiology before it, evolutionary psychology has been embroiled in controversy, but evolutionary psychologists see their field as gaining increased acceptance overall.

The Territorial Imperative: A Personal Inquiry Into the Animal Origins of Property and Nations is a 1966 nonfiction book by American writer Robert Ardrey. It characterizes an instinct among humans toward territoriality and the implications of this to property ownership and nation building. The Territorial Imperative was influential at the time, and encouraged public interest in human origins.

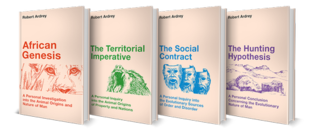

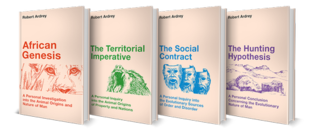

African Genesis: A Personal Investigation into the Animal Origins and Nature of Man, usually referred to as African Genesis, is a 1961 nonfiction work by the American writer Robert Ardrey. It posited the hypothesis that man evolved on the African continent from carnivorous, predatory ancestors who distinguished themselves from apes by the use of weapons. The work bears on questions of human origins, human nature, and human uniqueness. Although some of his ideas were refuted by later science, it was widely read and continues to inspire significant controversy.

The Hunting Hypothesis: A Personal Conclusion Concerning the Evolutionary Nature of Man is a 1976 work of paleoanthropology by Robert Ardrey. It is the final book in his widely read Nature of Man Series, which also includes African Genesis (1961) and The Territorial Imperative (1966).

The Social Contract: A Personal Inquiry into the Evolutionary Sources of Order and Disorder is a 1970 book by Robert Ardrey. It is the third in his four-book Nature of Man Series.

The Nature of Man Series is a four-volume series of works in paleoanthropology by the prolific playwright, screenwriter, and science writer Robert Ardrey. The books in the series were published between 1961 and 1976.

The Goodness Paradox: The Strange Relationship Between Virtue and Violence in Human Evolution is a book by British primatologist Richard Wrangham.

Der Begriff des Instinktes einst und jetzt is a book written by Heinrich Ernst Ziegler. Its first edition was published in the Zoologische Jahrbücher, Supplement VII in 1904. The second edition, published 1910 by Gustav Fisher in Jena and third edition, published in 1920 under the same publisher both received several extensions. The book is about the history of the concept instinct and the different conceptions of the animal psyche throughout history, as well as the understanding of these concepts at the time the book was published. Furthermore, it discusses the implications of Charles Darwin's theory of common descent for comparative psychology.