Bagpipes are a woodwind instrument using enclosed reeds fed from a constant reservoir of air in the form of a bag. The Great Highland bagpipes are well known, but people have played bagpipes for centuries throughout large parts of Europe, Northern Africa, Western Asia, around the Persian Gulf and northern parts of South Asia.

The uilleann pipes, sometimes called Irish bagpipes, are the characteristic national bagpipe of Ireland. Earlier known in English as "union pipes", their current name is a partial translation of the Irish language terms píobaí uilleann, from their method of inflation. There is no historical record of the name or use of the term uilleann pipes before the 20th century. It was an invention of Grattan Flood and the name stuck. People mistook the term 'union' to refer to the 1800 Act of Union; however, this is incorrect as Breandán Breathnach points out that a poem published in 1796 uses the term 'union'.

The chanter is the part of the bagpipe upon which the player creates the melody. It consists of a number of finger-holes, and in its simpler forms looks similar to a recorder. On more elaborate bagpipes, such as the Northumbrian bagpipes or the Uilleann pipes, it also may have a number of keys, to increase the instrument's range and/or the number of keys it can play in. Like the rest of the bagpipe, they are often decorated with a variety of substances, including metal (silver/nickel/gold/brass), bone, ivory, or plastic mountings.

The great Highland bagpipe is a type of bagpipe native to Scotland, and the Scottish analogue to the great Irish warpipes. It has acquired widespread recognition through its usage in the British military and in pipe bands throughout the world.

The Scottish smallpipe is a bellows-blown bagpipe re-developed by Colin Ross and many others, adapted from an earlier design of the instrument. There are surviving bellows-blown examples of similar historical instruments as well as the mouth-blown Montgomery smallpipes, dated 1757, which are held in the National Museum of Scotland. Some instruments are being built as direct copies of historical examples, but few modern instruments are directly modelled on older examples; the modern instrument is typically larger and lower-pitched. The innovations leading to the modern instrument, in particular the design of the reeds, were largely taken from the Northumbrian smallpipes.

The border pipes are a type of bagpipe related to the Scottish Great Highland Bagpipe. It is perhaps confusable with the Scottish smallpipe, although it is a quite different and much older instrument. Although most modern Border pipes are closely modelled on similar historic instruments, the modern Scottish smallpipes are a modern reinvention, inspired by historic instruments but largely based on Northumbrian smallpipes in their construction.

Swedish bagpipes are a variety of bagpipes from Sweden. The term itself generically translates to "bagpipes" in Swedish, but is used in English to describe the specifically Swedish bagpipe from the Dalarna region.

The Northumbrian smallpipes are bellows-blown bagpipes from Northeastern England, where they have been an important factor in the local musical culture for more than 250 years. The family of the Duke of Northumberland have had an official piper for over 250 years. The Northumbrian Pipers' Society was founded in 1928, to encourage the playing of the instrument and its music; Although there were so few players at times during the last century that some feared the tradition would die out, there are many players and makers of the instrument nowadays, and the Society has played a large role in this revival. In more recent times the Mayor of Gateshead and the Lord Mayor of Newcastle have both established a tradition of appointing official Northumbrian pipers.

The Hungarian duda is the traditional bagpipe of Hungary. It is an example of a group of bagpipes called Medio-Carparthian bagpipes.

Cornish bagpipes are the forms of bagpipes once common in Cornwall in the 19th century. Bagpipes and pipes are mentioned in Cornish documentary sources from c.1150 to 1830 and bagpipes are present in Cornish iconography from the 15th and 16th centuries.

The Brian Boru bagpipe was invented and patented in 1908 by Henry Starck, an instrument maker, in London, in consultation with William O'Duane. The name was chosen in honour of the Irish king Brian Boru (941–1014), though this bagpipe is not a recreation of any pipes that were played at the time of his reign.

Welsh bagpipes The names in Welsh refer specifically to a bagpipe. A related instrument is one type of bagpipe chanter, which when played without the bag and drone is called a pibgorn (English:hornpipe). The generic term pibau (pipes) which covers all woodwind instruments is also used. They have been played, documented, represented and described in Wales since the fourteenth century. A piper in Welsh is called a pibydd or a pibgodwr.

This article defines a number of terms that are exclusive, or whose meaning is exclusive, to piping and pipers.

The electronic bagpipes is an electronic musical instrument emulating the tone and/or playing style of the bagpipes. Most electronic bagpipe emulators feature a simulated chanter, which is used to play the melody. Some models also produce a harmonizing drone(s). Some variants employ a simulated bag, wherein the player's pressure on the bag activates a switch maintaining a constant tone. As with other electronic musical instruments, they must be plugged into an instrument amplifier and loudspeaker to hear the sound. Some electronic bagpipes are MIDI controllers that can be plugged into a synth module to create synthesized or sampled bagpipe sounds.

When bagpipes arrived in England is unknown, there is some evidence to suggest Anglo-Saxon times, however the oldest confirmed proof of the existence of bagpipes anywhere in the world comes from three separate sources in the 13th century. Two of them English; the Tenison Marginalie Psalter from Westminster and an entry into the accounts books of Edward the I of England recording the purchase of a set of bagpipes. The third from the Cantigas Del Santa Maria published in Spain. From the 14th century onwards, bagpipes start to appear in the historical records of European countries, however half the mentions come from England suggesting Bagpipes were more common in England.

Hugh Robertson (1730–1822) was a Scottish wood and ivory turner and a master crafter of woodwind instruments such as pastoral pipes, union pipes, and great Highland bagpipes.

John Dunn was a noted pipemaker, or maker of bagpipes. Born in Newcastle upon Tyne, England, Dunn was a cabinet maker by profession, initially a junior partner with George Brummell. In the trade directories, he also appears in his own right as a turner and a plumb maker and turner. His address was Bell's Court, off Pilgrim Street. He was buried on 6 February 1820 in St. John's, Newcastle. His father may have been one John Dunn of Longhorsley; if so, he was born on 3 September 1764. He should not be confused with one M. Dunn, the maker of several surviving sets of Union pipes.

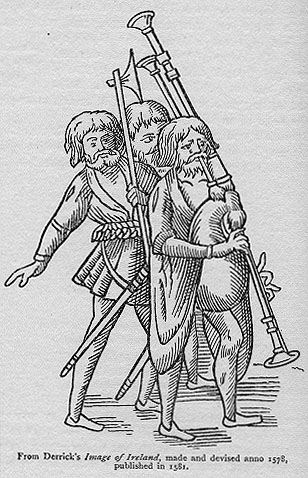

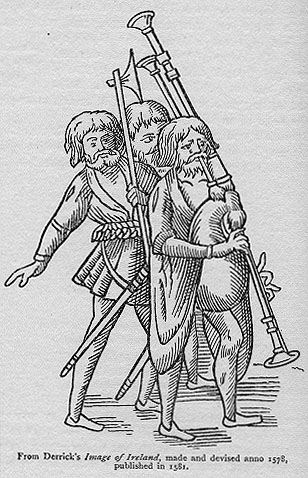

Irish warpipes are an Irish analogue of the Scottish great Highland bagpipe. "Warpipes" is originally an English term. The first use of the Gaelic term in Ireland was recorded in a poem by Seán Ó Neachtain, in which the bagpipes are referred to as píb mhór.