An amphora is a type of container with a pointed bottom and characteristic shape and size which fit tightly against each other in storage rooms and packages, tied together with rope and delivered by land or sea. The size and shape have been determined from at least as early as the Neolithic Period. Amphorae were used in vast numbers for the transport and storage of various products, both liquid and dry, but mostly for wine. They are most often ceramic, but examples in metals and other materials have been found. Versions of the amphorae were one of many shapes used in Ancient Greek vase painting.

The Anthesteria was one of the four Athenian festivals in honor of Dionysus. It was held each year from the 11th to the 13th of the month of Anthesterion, around the time of the January or February full moon. The three days of the feast were called Pithoigia, Choës, and Chytroi.

In the religion of ancient Rome, a haruspex was a person trained to practise a form of divination called haruspicy, the inspection of the entrails of sacrificed animals, especially the livers of sacrificed sheep and poultry. Various ancient cultures of the Near East, such as the Babylonians, also read omens specifically from the liver, a practice also known by the Greek term hepatoscopy.

A chalice is a drinking cup raised on a stem with a foot or base. The word is now used almost exclusively for the cups used in Christian liturgy as part of a service of the Eucharist, such as a Catholic mass. These are normally made of metal, but neither the shape nor the material is a requirement. Most have no handles, and in recent centuries the cup at the top has usually been a simple flared shape.

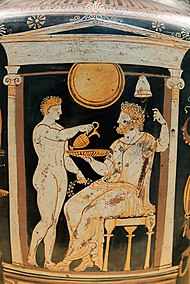

A libation is a ritual pouring of a liquid as an offering to a deity or spirit, or in memory of the dead. It was common in many religions of antiquity and continues to be offered in cultures today.

Religious practices in ancient Greece encompassed a collection of beliefs, rituals, and mythology, in the form of both popular public religion and cult practices. The application of the modern concept of "religion" to ancient cultures has been questioned as anachronistic. The ancient Greeks did not have a word for 'religion' in the modern sense. Likewise, no Greek writer known to us classifies either the gods or the cult practices into separate 'religions'. Instead, for example, Herodotus speaks of the Hellenes as having "common shrines of the gods and sacrifices, and the same kinds of customs."

A rhyton is a roughly conical container from which fluids were intended to be drunk or to be poured in some ceremony such as libation, or merely at table; in other words, a cup. A rhyton is typically formed in the shape of either an animal's head or an animal horn; in the latter case it often terminates in the shape of an animal's body. Rhyta were produced over large areas of ancient Eurasia during the Bronze and Iron Ages, especially from Persia to the Balkans.

Walter Burkert was a German scholar of Greek mythology and cult.

In the pottery of ancient Greece, a kylix is the most common type of cup in the period, usually associated with the drinking of wine. The cup often consists of a rounded base and a thin stem under a basin. The cup is accompanied by two handles on opposite sides.

In Ancient Greece, the symposium was the part of a banquet that took place after the meal, when drinking for pleasure was accompanied by music, dancing, recitals, or conversation. Literary works that describe or take place at a symposium include two Socratic dialogues, Plato's Symposium and Xenophon's Symposium, as well as a number of Greek poems, such as the elegies of Theognis of Megara. Symposia are depicted in Greek and Etruscan art, that shows similar scenes.

A bowl is a typically round dish or container generally used for preparing, serving, storing, or consuming food. The interior of a bowl is characteristically shaped like a spherical cap, with the edges and the bottom forming a seamless curve. This makes bowls especially suited for holding liquids and loose food, as the contents of the bowl are naturally concentrated in its center by the force of gravity. The exterior of a bowl is most often round, but can be of any shape, including rectangular.

The epulones was a religious organization of Ancient Rome. They arranged feasts and public banquets at festivals and games (ludi). They constituted one of the four great religious corporations of ancient Roman priests.

A kantharos or cantharus is a type of ancient Greek cup used for drinking. Although almost all surviving examples are in Greek pottery, the shape, like many Greek vessel types, probably originates in metalwork. In its iconic "Type A" form, it is characterized by its deep bowl, tall pedestal foot, and pair of high-swung handles which extend above the lip of the pot. The Greek words kotylos and kotyle are other ancient names for this same shape.

In ancient Roman culture, the olla is a squat, rounded pot or jar. An olla would be used primarily to cook or store food, hence the word "olla" is still used in some Romance languages for either a cooking pot or a dish in the sense of cuisine. In the typology of ancient Roman pottery, the olla is a vessel distinguished by its rounded "belly", typically with no or small handles or at times with volutes at the lip, and made within a Roman sphere of influence; the term olla may also be used for Etruscan and Gallic examples, or Greek pottery found in an Italian setting.

In the Hellenic religion, nephalia was the religious name for libations, in which wine was not offered or the use of wine was explicitly forbidden. Liquids, such as water, milk, honey or oil in any combination, were used with a mixture of honey and water or milk, being one of the most common nēphália offerings. Nephalia were performed as both independent rituals and in conjunction with other sacrifices, such as animal sacrifices. The use of nēphália is documented in the works of Aeschylus and Porphyry.

The Mars of Todi is a near life-sized bronze warrior, dating from the late 5th or early 4th century BC, believed to have been produced in Etruria for the Umbrian tribe. It was found near Todi, on the slope of Montesanto, in the property of the Franciscan Convent of Montesanto.

A cup is an open-top vessel (container) used to hold liquids for drinking, typically with a flattened hemispherical shape, and often with a capacity of about 100–250 millilitres (3–8 US fl oz). Cups may be made of pottery, glass, metal, wood, stone, polystyrene, plastic, lacquerware, or other materials. Normally, a cup is brought in contact with the mouth for drinking, distinguishing it from other tableware and drinkware forms such as jugs. They also most typically have handles, though a beaker has no handle or stem, and small bowl shapes are very common in Asia.

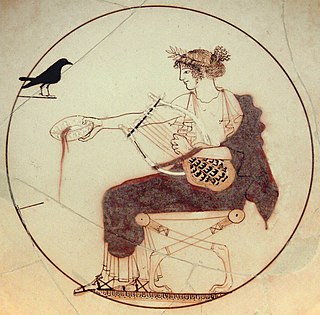

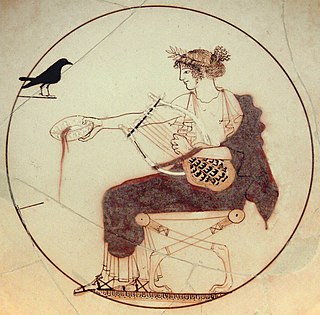

The few pottery exhibits of the Delphi Archaeological Museum include a famous shallow bowl (kylix) with an unusual depiction of the god Apollo. In the white-ground red-figure technique, it was found in a grave underneath the museum.

Ancient Greek funerary vases are decorative grave markers made in ancient Greece that were designed to resemble liquid-holding vessels. These decorated vases were placed on grave sites as a mark of elite status. There are many types of funerary vases, such as amphorae, kraters, oinochoe, and kylix cups, among others. One famous example is the Dipylon amphora. Every-day vases were often not painted, but wealthy Greeks could afford luxuriously painted ones. Funerary vases on male graves might have themes of military prowess, or athletics. However, allusions to death in Greek tragedies was a popular motif. Famous centers of vase styles include Corinth, Lakonia, Ionia, South Italy, and Athens.

Ceremonies of Ancient Greece encompasses those practices of a formal religious nature celebrating particular moments in the life of the community or individual in Greece from the period of the Greek dark ages to the middle ages. Ancient Greek religion was not standardised and had no formalised canon of religious texts, nor single priestly hierarchy, and practices varied greatly. However, ceremonial life in pre-Christian Greece generally involved offerings of a variety of forms towards gods and heroes, as well as a plethora of public celebrations such as weddings, burial rites, and festivals.