This article should specify the language of its non-English content using {{ lang }} or {{ langx }}, {{ transliteration }} for transliterated languages, and {{ IPA }} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used.(February 2025) |

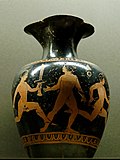

The pottery of ancient Greece has a long history and the form of Greek vase shapes has had a continuous evolution from Minoan pottery down to the Hellenistic period. As Gisela Richter puts it, the forms of these vases (by convention the term "vase" has a very broad meaning in the field, covering anything that is a vessel of some sort) find their "happiest expression" in the 5th and 6th centuries BC, yet it has been possible to date vases thanks to the variation in a form’s shape over time, a fact particularly useful when dating unpainted or plain black-gloss ware.

Contents

- Overview

- Vase shapes

- Styles of lips and feet

- See also

- Notes

- References

- Further reading

- External links

The task of naming Greek vase shapes is by no means a straightforward one. The endeavour by archaeologists to match vase forms with those names that have come down to us from Greek literature began with Theodor Panofka’s 1829 book Recherches sur les veritables noms des vases grecs, whose confident assertion that he had rediscovered the ancient nomenclature was quickly disputed by Gerhard and Letronne.

A few surviving vases were labelled with their names in antiquity; these included a hydria depicted on the François Vase and a kylix that declares, “I am the decorated kylix of lovely Phito” (BM, B450). Vases in use are sometimes depicted in paintings on vases, which can help scholars interpret written descriptions. Much of our written information about Greek pots come from such late writers as Athenaios and Pollux and other lexicographers who described vases unknown to them, and their accounts are often contradictory or confused. With those caveats, the names of Greek vases are fairly well settled, even if such names are a matter of convention rather than historical fact.

The following vases are mostly Attic, from the 5th and 6th centuries, and follow the Beazley naming convention. Many shapes derive from metal vessels, especially in silver, which survive in far smaller numbers. Some pottery vases were probably intended as cheaper substitutes for these, either for use or to be placed as grave goods. Some terms, especially among the types of kylix or drinking cup, combine a shape and a type or location of decoration, as in the band cup, eye cup and others. Some terms are defined by function as much as shape, such as the aryballos , which later potters turned into all sorts of fancy novelty shapes.