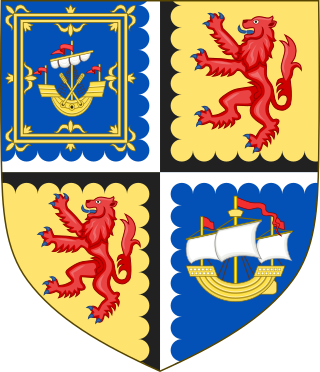

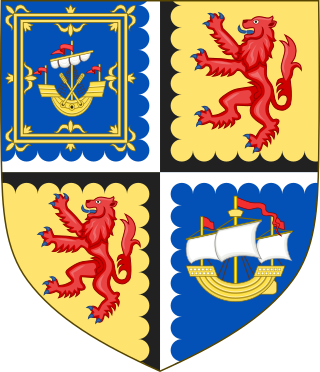

William Sinclair (1410–1480), 1st Earl of Caithness (1455–1476), last Earl (Jarl) of Orkney, 2nd Lord Sinclair and 11th Baron of Roslin was a Norwegian and Scottish nobleman and the builder of Rosslyn Chapel, in Midlothian.

Earl of Orkney, historically Jarl of Orkney, is a title of nobility encompassing the archipelagoes of Orkney and Shetland, which comprise the Northern Isles of Scotland. Originally founded by Norse invaders, the status of the rulers of the Northern Isles as Norwegian vassals was formalised in 1195. Although the Old Norse term jarl is etymologically related to "earl", and the jarls were succeeded by earls in the late 15th century, a Norwegian jarl is not the same thing. In the Norse context the distinction between jarls and kings did not become significant until the late 11th century and the early jarls would therefore have had considerable independence of action until that time. The position of Jarl of Orkney was eventually the most senior rank in medieval Norway except for the king himself.

Scalloway Castle is a tower house in Scalloway, on the Shetland Mainland, the largest island in the Shetland Islands of Scotland. The tower was built in 1600 by Patrick Stewart, 2nd Earl of Orkney, during his brief period as de facto ruler of Shetland.

St Magnus Cathedral dominates the skyline of Kirkwall, the main town of Orkney, a group of islands off the north coast of mainland Scotland. Originally Roman Catholic, it is the oldest cathedral in Scotland and the most northerly cathedral in the United Kingdom - a fine example of Romanesque architecture built when the islands were ruled by the Norse Earls of Orkney. Today it is owned not by any church, but by the burgh of Kirkwall as a result of an act of King James III of Scotland following Orkney's annexation by the Scottish Crown in 1468.

The Earl's Palace is a ruined Renaissance-style palace near St Magnus's Cathedral in the centre of Kirkwall, Orkney, Scotland. Built by Patrick, Earl of Orkney, its construction began in 1607 and was largely undertaken via forced labour. Today, the ruins are open to the public.

The Bishop's Palace, Kirkwall is a 12th-century palace built at the same time as the adjacent St Magnus Cathedral in the centre of Kirkwall, Orkney, Scotland. It housed the cathedral's first bishop, William the Old of the Norwegian Catholic Church who took his authority from the Archbishop of Nidaros (Trondheim). The ruined structure now looks like a small castle.

Laurence Bruce of Cultmalindie was a Scottish landowner and factor to the Earl of Orkney. He features in a number of traditional stories of Shetland.

Robert Stewart, 1st Earl of Orkney and Lord of Zetland (Shetland) was a recognised illegitimate son of James V, King of Scotland, and his mistress Eupheme Elphinstone. Robert Stewart was half-brother to Mary, Queen of Scots and uncle to James VI and I of Scotland and England.

Gilbert Balfour was a 16th-century Scottish courtier and mercenary captain. He probably played a leading role in the murder of Lord Darnley, consort of Mary, Queen of Scots.

Kirkwall Castle, also known as King's Castle, was located in Kirkwall, the main settlement in the Orkney Islands of Scotland. Built in the 14th century, it was deliberately destroyed in 1614. The last ruins were cleared in the 19th century. The castle was located around the corner of Broad Street and Castle Street in the centre of Kirkwall.

John Stewart, Earl of Carrick, Lord Kinclaven was a Scottish nobleman, the third son of Robert, Earl of Orkney, a bastard son of King James V.

The 1594 trial of alleged witch Allison Balfour or Margaret Balfour is one of the most frequently cited Scottish witchcraft cases. Balfour lived in the Orkney Islands of Scotland in the area of Stenness. At that time in Scotland, the Scottish Witchcraft Act 1563 had made a conviction for witchcraft punishable by death.

Witchcraft in Orkney possibly has its roots in the settlement of Norsemen on the archipelago from the eighth century onwards. Until the early modern period magical powers were accepted as part of the general lifestyle, but witch-hunts began on the mainland of Scotland in about 1550, and the Scottish Witchcraft Act of 1563 made witchcraft or consultation with witches a crime punishable by death. One of the first Orcadians tried and executed for witchcraft was Allison Balfour, in 1594. Balfour, her elderly husband and two young children, were subjected to severe torture for two days to elicit a confession from her.

The Sheriff of Orkney and Shetland, also known as the Sheriff of Orkney and Zetland, was historically the royal official responsible for enforcing law and order in Orkney and Shetland, Scotland. The office was combined with the role in Shetland of the "foud" and the "foudry". The foud was a bailiff who returned customs and rents due the crown, including butter and oil known as "fat goods".

Margaret Stewart, Mistress of Ochiltree was a courtier in the household of Anne of Denmark in Scotland and looked after her children Prince Henry, Princess Elizabeth, and Charles I of England

John Sinclair, Master of Caithness was a Scottish nobleman.

George Sinclair was a Scottish nobleman, the 5th Earl of Caithness and chief of the Clan Sinclair, a Scottish clan based in northern Scotland.

Henry Sinclair was a Scottish noble and the 4th Lord Sinclair. In The Scots Peerage by James Balfour Paul he is designated as the 3rd Lord Sinclair, but historian Roland Saint-Clair designates him the 4th Lord Sinclair and references this to an Act of the Scottish Parliament in which he was made Lord Sinclair based on his descent from his great-grandfather, Henry II Sinclair, Earl of Orkney, the first Lord Sinclair. Bernard Burke, in his a Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage of the British Empire, agrees with Roland Saint-Clair and says that Henry Sinclair was "in reality" the fourth holder of the title of Lord Sinclair.

William Sinclair was a Scottish nobleman and the 5th Lord Sinclair. In The Scots Peerage by James Balfour Paul he is designated as the 4th Lord Sinclair in descent starting from William Sinclair, 1st Earl of Caithness and 3rd Earl of Orkney, but historian Roland Saint-Clair designates him as the 5th Lord Sinclair in descent from the father of the 1st Earl of Caithness and 3rd Earl of Orkney, Henry II Sinclair, Earl of Orkney, who is the first person recorded as Lord Sinclair in public records. Roland Saint-Clair references this to an Act of the Scottish Parliament in which the 4th Lord Sinclair was made Lord Sinclair based on his descent from his great-grandfather, Henry II Sinclair, Earl of Orkney, the first Lord Sinclair. Bernard Burke, in his a Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage of the British Empire, agrees with Roland Saint-Clair and says that William Sinclair was "in reality" the fifth Lord Sinclair.

Hugh or Huw Kennedy of Girvanmains was a Scottish courtier, soldier, and landowner.