A trow is a malignant or mischievous fairy or spirit in the folkloric traditions of the Orkney and Shetland islands. Trows may be regarded as monstrous giants at times, or quite the opposite, short-statured fairies dressed in grey.

Isobel Gowdie was a Scottish woman who confessed to witchcraft at Auldearn near Nairn during 1662. Scant information is available about her age or life and, although she was probably executed in line with the usual practice, it is uncertain whether this was the case or if she was allowed to return to the obscurity of her former life as a cottar’s wife. Her detailed testimony, apparently achieved without the use of violent torture, provides one of the most comprehensive insights into European witchcraft folklore at the end of the era of witch-hunts.

Shapinsay is one of the Orkney Islands off the north coast of mainland Scotland. With an area of 29.5 square kilometres (11.4 sq mi), it is the eighth largest island in the Orkney archipelago. It is low-lying and, with a bedrock formed from Old Red Sandstone overlain by boulder clay, fertile. Consequently, most of the area is given over to farming. Shapinsay has two nature reserves and is notable for its bird life. Balfour Castle, built in the Scottish Baronial style, is one of the island's most prominent features, a reminder of the Balfour family's domination of Shapinsay during the 18th and 19th centuries; the Balfours transformed life on the island by introducing new agricultural techniques. Other landmarks include a standing stone, an Iron Age broch, a souterrain and a salt-water shower.

Evie is a parish and village on Mainland, Orkney, Scotland. The parish is located in the north-west of the Mainland, between Birsay and Rendall, forming the coastline opposite the isle of Rousay.

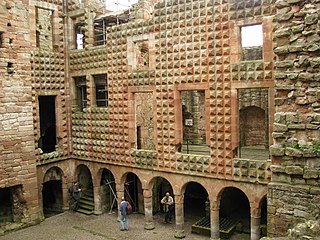

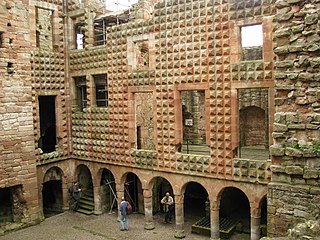

Patrick Stewart, 2nd Earl of Orkney, Lord of Zetland was a Scottish nobleman, the son of Robert, Earl of Orkney, a bastard son of King James V. Infamous for his godless nature and tyrannical rule over the Scottish archipelagos of Orkney and Shetland, he was executed for treason in 1615.

Robert Stewart, 1st Earl of Orkney and Lord of Zetland (Shetland) was a recognised illegitimate son of James V, King of Scotland, and his mistress Eupheme Elphinstone. Robert Stewart was half-brother to Mary, Queen of Scots and uncle to James VI and I of Scotland and England.

Gilbert Balfour was a 16th-century Scottish courtier and mercenary captain. He probably played a leading role in the murder of Lord Darnley, consort of Mary, Queen of Scots.

Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell, was Commendator of Kelso Abbey and Coldingham Priory, a Privy Counsellor and Lord High Admiral of Scotland. He was a notorious conspirator who led several uprisings against his first cousin, King James VI, all of which ultimately failed, and he died in poverty in Italy after being banished from Scotland. Francis's maternal uncle, the 4th Earl of Bothwell, was the chief suspect in the murder of James VI's father, Lord Darnley.

In early modern Scotland, in between the early 16th century and the mid-18th century, judicial proceedings concerned with the crimes of witchcraft took place as part of a series of witch trials in Early Modern Europe. In the late middle age there were a handful of prosecutions for harm done through witchcraft, but the passing of the Witchcraft Act 1563 made witchcraft, or consulting with witches, capital crimes. The first major issue of trials under the new act were the North Berwick witch trials, beginning in 1590, in which King James VI played a major part as "victim" and investigator. He became interested in witchcraft and published a defence of witch-hunting in the Daemonologie in 1597, but he appears to have become increasingly sceptical and eventually took steps to limit prosecutions.

The great Scottish witch hunt of 1649–50 was a series of witch trials in Scotland. It is one of five major hunts identified in early modern Scotland and it probably saw the most executions in a single year.

John Stewart, Earl of Carrick, Lord Kinclaven was a Scottish nobleman, the third son of Robert, Earl of Orkney, a bastard son of King James V.

Witchcraft in Orkney possibly has its roots in the settlement of Norsemen on the archipelago from the eighth century onwards. Until the early modern period magical powers were accepted as part of the general lifestyle, but witch-hunts began on the mainland of Scotland in about 1550, and the Scottish Witchcraft Act of 1563 made witchcraft or consultation with witches a crime punishable by death. One of the first Orcadians tried and executed for witchcraft was Allison Balfour, in 1594. Balfour, her elderly husband and two young children, were subjected to severe torture for two days to elicit a confession from her.

Elspeth Reoch was an alleged Scottish witch. She was born in Caithness but as a child spent time with relatives on an island in Lochaber prior to travelling to the mainland of Orkney.

Margaret Aitken, known as the Great Witch of Balwearie, was an important figure in the great Scottish witchcraft panic of 1597 as her actions effectively led to an end of that series of witch trials. After being accused of witchcraft Aitken confessed but then identified hundreds of women as other witches to save her own life. She was exposed as a fraud a few months later and was burnt at the stake.

The Bute witches were six Scottish women accused of witchcraft and interrogated in the parish of Rothesay on Bute during the Great Scottish Witch Hunt of 1661–62. The Privy Council granted a Commission of Justiciary for a local trial to be held and four of the women – believed by historians to be Margaret McLevin, Margaret McWilliam, Janet Morrison and Isobell McNicoll – were executed in 1662; a fifth may have died while incarcerated. One woman, Jonet NcNicoll, escaped from prison before she could be executed but when she returned to the island in 1673 the sentence was implemented.

Beatrix Leslie was a Scottish midwife executed for witchcraft. In 1661 she was accused of causing the collapse of a coal pit through witchcraft. Little is known about her life before that, although there are reported disputes with neighbours that allude to a quarrelsome attitude.

John Arnot of Birswick (Orkney) (1530–1616) was a 16th-century Scottish merchant and landowner who served as Lord Provost of Edinburgh from 1587 to 1591 and from 1608 to death. He was Deputy Treasurer to King James VI.

Peder Munk of Estvadgård (1534–1623), was a Danish navigator, politician, and ambassador, who was in charge of the fleet carrying Anne of Denmark to Scotland. The events of the voyage led to witch trials and executions in Denmark and Scotland.

Robert Colville of Cleish (1532–1584) was a Scottish courtier.

Anne of Denmark (1574–1619) was the wife of King James VI and I, and as such Queen of Scotland from their marriage by proxy on 20 August 1589 and Queen of England and Ireland from 24 March 1603 until her death in 1619. When Anne intended to sail to Scotland in 1589 her ship was delayed by adverse weather. Contemporary superstition blamed the delays to her voyage and other misfortunes on "contrary winds" summoned by witchcraft. There were witchcraft trials in Denmark and in Scotland. The King's kinsman, Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell came into suspicion. The Chancellor of Scotland John Maitland of Thirlestane, thought to be Bothwell's enemy, was lampooned in a poem Rob Stene's Dream, and Anne of Denmark made Maitland her enemy. Historians continue to investigate these events.