A trow is a malignant or mischievous fairy or spirit in the folkloric traditions of the Orkney and Shetland islands. Trows may be regarded as monstrous giants at times, or quite the opposite, short-statured fairies dressed in grey.

Isobel Gowdie was a Scottish woman who confessed to witchcraft at Auldearn near Nairn during 1662. Scant information is available about her age or life and, although she was probably executed in line with the usual practice, it is uncertain whether this was the case or if she was allowed to return to the obscurity of her former life as a cottar’s wife. Her detailed testimony, apparently achieved without the use of violent torture, provides one of the most comprehensive insights into European witchcraft folklore at the end of the era of witch-hunts.

Earl of Orkney, historically Jarl of Orkney, is a title of nobility encompassing the archipelagoes of Orkney and Shetland, which comprise the Northern Isles of Scotland. Originally founded by Norse invaders, the status of the rulers of the Northern Isles as Norwegian vassals was formalised in 1195. Although the Old Norse term jarl is etymologically related to "earl", and the jarls were succeeded by earls in the late 15th century, a Norwegian jarl is not the same thing. In the Norse context the distinction between jarls and kings did not become significant until the late 11th century and the early jarls would therefore have had considerable independence of action until that time. The position of Jarl of Orkney was eventually the most senior rank in medieval Norway except for the king himself.

The North Berwick witch trials were the trials in 1590 of a number of people from East Lothian, Scotland, accused of witchcraft in the St Andrew's Auld Kirk in North Berwick on Halloween night. They ran for two years, and implicated over 70 people. These included Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell, on charges of high treason.

Patrick Stewart, 2nd Earl of Orkney, Lord of Zetland was a Scottish nobleman, the son of Robert, Earl of Orkney, a bastard son of King James V. Infamous for his godless nature and tyrannical rule over the Scottish archipelagos of Orkney and Shetland, he was executed for treason in 1615.

Ragnhild Eriksdotter was the daughter of Eric Bloodaxe and his wife, Gunnhild. According to the Orkneyinga Saga, she was an ambitious and scheming woman who sought power through the men of the family of Thorfinn Torf-Einarsson, who was Earl of Orkney. The period after Thorfinn's death was one of dynastic strife.

The Paisley witches, also known as the Bargarran witches or the Renfrewshire witches, were tried in Paisley, Renfrewshire, central Scotland, in 1697. Eleven-year-old Christian Shaw, daughter of the Laird of Bargarran, complained of being tormented by some local witches; they included one of her family's servants, Catherine Campbell, whom she had reported to her mother after witnessing her steal a drink of milk.

In early modern Scotland, in between the early 16th century and the mid-18th century, judicial proceedings concerned with the crimes of witchcraft took place as part of a series of witch trials in Early Modern Europe. In the late middle age there were a handful of prosecutions for harm done through witchcraft, but the passing of the Witchcraft Act 1563 made witchcraft, or consulting with witches, capital crimes. The first major issue of trials under the new act were the North Berwick witch trials, beginning in 1590, in which King James VI played a major part as "victim" and investigator. He became interested in witchcraft and published a defence of witch-hunting in the Daemonologie in 1597, but he appears to have become increasingly sceptical and eventually took steps to limit prosecutions.

The great Scottish witch hunt of 1649–50 was a series of witch trials in Scotland. It is one of five major hunts identified in early modern Scotland and it probably saw the most executions in a single year.

The 1594 trial of alleged witch Allison Balfour or Margaret Balfour is one of the most frequently cited Scottish witchcraft cases. Balfour lived in the Orkney Islands of Scotland in the area of Stenness. At that time in Scotland, the Scottish Witchcraft Act 1563 had made a conviction for witchcraft punishable by death.

Witchcraft in Orkney possibly has its roots in the settlement of Norsemen on the archipelago from the eighth century onwards. Until the early modern period magical powers were accepted as part of the general lifestyle, but witch-hunts began on the mainland of Scotland in about 1550, and the Scottish Witchcraft Act of 1563 made witchcraft or consultation with witches a crime punishable by death. One of the first Orcadians tried and executed for witchcraft was Allison Balfour, in 1594. Balfour, her elderly husband and two young children, were subjected to severe torture for two days to elicit a confession from her.

The Pittenweem witches were five Scottish women accused of witchcraft in the small fishing village of Pittenweem in Fife on the east coast of Scotland in 1704. Another two women and a man were named as accomplices. Accusations made by a teenage boy, Patrick Morton, against a local woman, Beatrix Layng, led to the death in prison of Thomas Brown, and, in January 1705, the murder of Janet Cornfoot by a lynch mob in the village.

Margaret Aitken, known as the Great Witch of Balwearie, was an important figure in the great Scottish witchcraft panic of 1597 as her actions effectively led to an end of that series of witch trials. After being accused of witchcraft Aitken confessed but then identified hundreds of women as other witches to save her own life. She was exposed as a fraud a few months later and was burnt at the stake.

The Bute witches were six Scottish women accused of witchcraft and interrogated in the parish of Rothesay on Bute during the Great Scottish Witch Hunt of 1661–62. The Privy Council granted a Commission of Justiciary for a local trial to be held and four of the women – believed by historians to be Margaret McLevin, Margaret McWilliam, Janet Morrison and Isobell McNicoll – were executed in 1662; a fifth may have died while incarcerated. One woman, Jonet NcNicoll, escaped from prison before she could be executed but when she returned to the island in 1673 the sentence was implemented.

Barbara Napier or Naper was a Scottish woman involved in the 1591 North Berwick witch trials. Details of charges against her survive, and she was found guilty of consulting with witches, but it is unclear if, like the other accused people, she was executed.

John Arnot of Birswick (Orkney) (1530–1616) was a 16th-century Scottish merchant and landowner who served as Lord Provost of Edinburgh from 1587 to 1591 and from 1608 to death. He was Deputy Treasurer to King James VI.

Alison Pearson was executed for witchcraft. On being tried in 1588, she confessed to visions of a fairy court.

Peder Munk of Estvadgård (1534–1623), was a Danish navigator, politician, and ambassador, who was in charge of the fleet carrying Anne of Denmark to Scotland. The events of the voyage led to witch trials and executions in Denmark and Scotland.

Anne of Denmark (1574–1619) was the wife of King James VI and I, and as such Queen of Scotland from their marriage by proxy on 20 August 1589 and Queen of England and Ireland from 24 March 1603 until her death in 1619. When Anne intended to sail to Scotland in 1589 her ship was delayed by adverse weather. Contemporary superstition blamed the delays to her voyage and other misfortunes on "contrary winds" summoned by witchcraft. There were witchcraft trials in Denmark and in Scotland. The King's kinsman, Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell came into suspicion. The Chancellor of Scotland John Maitland of Thirlestane, thought to be Bothwell's enemy, was lampooned in a poem Rob Stene's Dream, and Anne of Denmark made Maitland her enemy. Historians continue to investigate these events.

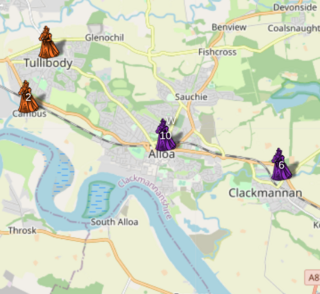

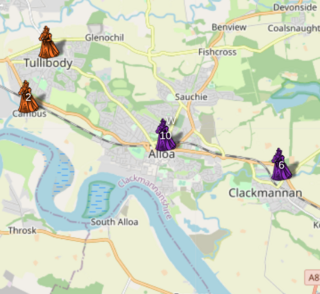

Margaret Duchill was a Scottish woman who confessed to witchcraft at Alloa during the year 1658. She was implicated by others and she named other women. She was executed on 1 June 1658.