Related Research Articles

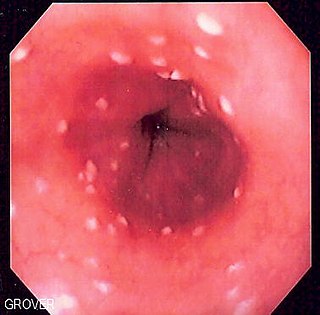

Esophageal candidiasis is an opportunistic infection of the esophagus by Candida albicans. The disease usually occurs in patients in immunocompromised states, including post-chemotherapy and in AIDS. However, it can also occur in patients with no predisposing risk factors, and is more likely to be asymptomatic in those patients. It is also known as candidal esophagitis or monilial esophagitis.

Aspergillosis is a fungal infection of usually the lungs, caused by the genus Aspergillus, a common mould that is breathed in frequently from the air, but does not usually affect most people. It generally occurs in people with lung diseases such as asthma, cystic fibrosis or tuberculosis, or those who are immunocompromised such as those who have had a stem cell or organ transplant or those who take medications such as steroids and some cancer treatments which suppress the immune system. Rarely, it can affect skin.

Cochliobolus lunatus is a fungal plant pathogen that can cause disease in humans and other animals. The anamorph of this fungus is known as Curvularia lunata, while C. lunatus denotes the teleomorph or sexual stage. They are, however, the same biological entity. C. lunatus is the most commonly reported species in clinical cases of reported Cochliobolus infection.

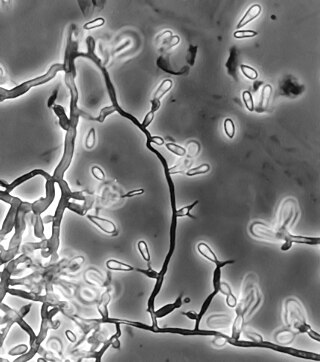

Exophiala jeanselmei is a saprotrophic fungus in the family Herpotrichiellaceae. Four varieties have been discovered: Exophiala jeanselmei var. heteromorpha, E. jeanselmei var. lecanii-corni, E. jeanselmei var. jeanselmei, and E. jeanselmei var. castellanii. Other species in the genus Exophiala such as E. dermatitidis and E. spinifera have been reported to have similar annellidic conidiogenesis and may therefore be difficult to differentiate.

Pseudallescheria boydii is a species of fungus classified in the Ascomycota. It is associated with some forms of eumycetoma/maduromycosis and is the causative agent of pseudallescheriasis. Typically found in stagnant and polluted water, it has been implicated in the infection of immunocompromised and near-drowned pneumonia patients. Treatment of infections with P. boydii is complicated by resistance to many of the standard antifungal agents normally used to treat infections by filamentous fungi.

Exophiala dermatitidis is a thermophilic black yeast, and a member of the Herpotrichiellaceae. While the species is only found at low abundance in nature, metabolically active strains are commonly isolated in saunas, steam baths, and dish washers. Exophiala dermatitidis only rarely causes infection in humans, however cases have been reported around the world. In East Asia, the species has caused lethal brain infections in young and otherwise healthy individuals. The fungus has been known to cause cutaneous and subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis, and as a lung colonist in people with cystic fibrosis in Europe. In 2002, an outbreak of systemic E. dermatitidis infection occurred in women who had received contaminated steroid injections at North Carolina hospitals.

Ochroconis gallopava, also called Dactylaria gallopava or Dactylaria constricta var. gallopava, is a member of genus Dactylaria. Ochroconis gallopava is a thermotolerant, darkly pigmented fungus that causes various infections in fowls, turkeys, poults, and immunocompromised humans first reported in 1986. Since then, the fungus has been increasingly reported as an agent of human disease especially in recipients of solid organ transplants. Ochroconis gallopava infection has a long onset and can involve a variety of body sites. Treatment of infection often involves a combination of antifungal drug therapy and surgical excision.

Apophysomyces variabilis is an emerging fungal pathogen that can cause serious and sometimes fatal infection in humans. This fungus is a soil-dwelling saprobe with tropical to subtropical distribution. It is a zygomycete that causes mucormycosis, an infection in humans brought about by fungi in the order Mucorales. Infectious cases have been reported globally in locations including the Americas, Southeast Asia, India, and Australia. Apophysomyces variabilis infections are not transmissible from person to person.

Coniochaeta hoffmannii, also known as Lecythophora hoffmannii, is an ascomycete fungus that grows commonly in soil. It has also been categorized as a soft-rot fungus capable of bringing the surface layer of timber into a state of decay, even when safeguarded with preservatives. Additionally, it has pathogenic properties, although it causes serious infection only in rare cases. A plant pathogen lacking a known sexual state, C. hoffmannii has been classified as a "dematiaceous fungus" despite its contradictory lack of pigmentation; both in vivo and in vitro, there is no correlation between its appearance and its classification.

Phaeohyphomycosis is a diverse group of fungal infections, caused by dematiaceous fungi whose morphologic characteristics in tissue include hyphae, yeast-like cells, or a combination of these. It can be associated with an array of melanistic filamentous fungi including Alternaria species, Exophiala jeanselmei, and Rhinocladiella mackenziei.

Thielavia subthermophila is a ubiquitous, filamentous fungus that is a member of the phylum Ascomycota and order Sordariales. Known to be found on plants of arid environments, it is an endophyte with thermophilic properties, and possesses dense, pigmented mycelium. Thielavia subthermophila has rarely been identified as a human pathogen, with a small number of clinical cases including ocular and brain infections. For treatment, antifungal drugs such as amphotericin B have been used topically or intravenously, depending upon the condition.

Sporobolomyces salmonicolor is a species of fungus in the subdivision Pucciniomycotina. It occurs in both a yeast state and a hyphal state, the latter formerly known as Sporidiobolus salmonicolor. It is generally considered a Biosafety Risk Group 1 fungus; however isolates of S. salmonicolor have been recovered from cerebrospinal fluid, infected skin, a nasal polyp, lymphadenitis and a case of endophthalmitis. It has also been reported in AIDS-related infections. The fungus exists predominantly in the anamorphic (asexual) state as a unicellular, haploid yeast yet this species can sometimes produce a teleomorphic (sexual) state when conjugation of compatible yeast cells occurs. The asexual form consists of a characteristic, pink, ballistosporic yeast. Ballistoconidia are borne from slender extensions of the cell known as sterigmata and are forcibly ejected into the air upon maturity. Levels of airborne yeast cells peak during the night and are abundant in areas of decaying leaves and grains. Three varieties of Sporobolomyces salmonicolor have been described; S. salmonicolor var. albus, S. salmonicolor var. fischerii, and S. salmonicolor var. salmoneus.

Scedosporiosis is the general name for any mycosis – i.e., fungal infection – caused by a fungus from the genus Scedosporium. Current population-based studies suggest Scedosporium prolificans and Scedosporium apiospermum to be among the most common infecting agents from the genus, although infections caused by other members thereof are not unheard of. The latter is an asexual form (anamorph) of another fungus, Pseudallescheria boydii. The former is a "black yeast", currently not characterized as well, although both of them have been described as saprophytes.

Phialemonium obovatum is a saprotrophic filamentous fungus able to cause opportunistic infections in humans with weakened immune systems. P. obovatum is widespread throughout the environment, occurring commonly in sewage, soil, air and water. Walter Gams and Michael McGinnis described the genus Phialemonium to accommodate species intermediate between the genera Acremonium and Phialophora. Currently, three species of Phialemonium are recognized of which P. obovatum is the only one to produce greenish colonies and obovate conidia. It has been investigated as one of several microfungi with potential use in the accelerated aging of wine.

Rhinocladiella mackenziei is a deeply pigmented mold that is a common cause of human cerebral phaeohyphomycosis. Rhinocladiella mackenziei was believed to be endemic solely to the Middle East, due to the first cases of infection being limited to the region. However, cases of R. mackenziei infection are increasingly reported from regions outside the Middle East. This pathogen is unique in that the majority of cases have been reported from immunologically normal people.

Phialophora verrucosa is a pathogenic, dematiaceous fungus that is a common cause of chromoblastomycosis. It has also been reported to cause subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis and mycetoma in very rare cases. In the natural environment, it can be found in rotting wood, soil, wasp nests, and plant debris. P. verrucosa is sometimes referred to as Phialophora americana, a closely related environmental species which, along with P. verrucosa, is also categorized in the P. carrionii clade.

Sarocladium kiliense is a saprobic fungus that is occasionally encountered as a opportunistic pathogen of humans, particularly immunocompromised and individuals. The fungus is frequently found in soil and has been linked with skin and systemic infections. This species is also known to cause disease in the green alga, Cladophora glomerata as well as various fruit and vegetable crops grown in warmer climates.

Trichosporon asteroides is an asexual basidiomycetous fungus first described from human skin but now mainly isolated from blood and urine. T. asteroides is a hyphal fungus with a characteristically yeast-like appearance due to the presence of slimy arthroconidia. Infections by this species usually respond to treatment with azoles and amphotericin B.

Cladophialophora arxii is a black yeast shaped dematiaceous fungus that is able to cause serious phaeohyphomycotic infections. C. arxii was first discovered in 1995 in Germany from a 22-year-old female patient suffering multiple granulomatous tracheal tumours. It is a clinical strain that is typically found in humans and is also capable of acting as an opportunistic fungus of other vertebrates Human cases caused by C. arxii have been reported from all parts of the world such as Germany and Australia.

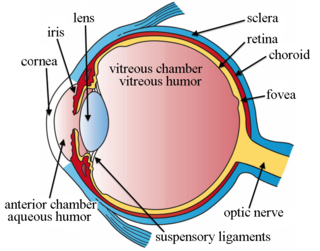

Intravitreal injection is the method of administration of drugs into the eye by injection with a fine needle. The medication will be directly applied into the vitreous humor. It is used to treat various eye diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetic retinopathy, and infections inside the eye such as endophthalmitis. As compared to topical administration, this method is beneficial for a more localized delivery of medications to the targeted site, as the needle can directly pass through the anatomical eye barrier and dynamic barrier. It could also minimize adverse drug effects on other body tissues via the systemic circulation, which could be a possible risk for intravenous injection of medications. Although there are risks of infections or other complications, with suitable precautions throughout the injection process, chances for these complications could be lowered.

References

- 1 2 Mycobank. "Phialemonium curvatum" . Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Perdomo, H.; Sutton, D. A.; Garcia, D.; Fothergill, A. W.; Gene, J.; Cano, J.; Summerbell, R. C.; Rinaldi, M. G.; Guarro, J. (26 January 2011). "Molecular and Phenotypic Characterization of Phialemonium and Lecythophora Isolates from Clinical Samples". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 49 (4): 1209–1216. doi:10.1128/JCM.01979-10. PMC 3122869 . PMID 21270235.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Proia, LA; Hayden, MK; Kammeyer, PL; Ortiz, J; Sutton, DA; Clark, T; Schroers, HJ; Summerbell, RC (Aug 1, 2004). "Phialemonium: an emerging mold pathogen that caused 4 cases of hemodialysis-associated endovascular infection". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 39 (3): 373–9. doi: 10.1086/422320 . PMID 15307005.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 King, D; Pasarell, L; Dixon, DM; McGinnis, MR; Merz, WG (July 1993). "A phaeohyphomycotic cyst and peritonitis caused by Phialemonium species and a reevaluation of its taxonomy". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 31 (7): 1804–10. doi:10.1128/JCM.31.7.1804-1810.1993. PMC 265636 . PMID 8349757.

- 1 2 3 Gams, W.; McGinnis M.R. (1983). "Phialemonium, a new anamorph genus intermediate between Phialophora and Acremonium". Mycologia. 75 (6): 977–987. doi:10.2307/3792653. JSTOR 3792653.

- 1 2 3 4 Osherov, A; Schwammenthal, E; Kuperstein, R; Strahilevitz, J; Feinberg, MS (July 2006). "Phialemonium curvatum prosthetic valve endocarditis with an unusual echocardiographic presentation". Echocardiography. 23 (6): 503–5. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8175.2006.00249.x. PMID 16839390. S2CID 12418775.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Strahilevitz, J; Rahav, G; Schroers, HJ; Summerbell, RC; Amitai, Z; Goldschmied-Reouven, A; Rubinstein, E; Schwammenthal, Y; Feinberg, MS; Siegman-Igra, Y; Bash, E; Polacheck, I; Zelazny, A; Howard, SJ; Cibotaro, P; Shovman, O; Keller, N (Mar 15, 2005). "An outbreak of Phialemonium infective endocarditis linked to intracavernous penile injections for the treatment of impotence". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 40 (6): 781–6. doi: 10.1086/428045 . PMID 15736008.

- 1 2 3 4 Dan, M; Yossepowitch, O; Hendel, D; Shwartz, O; Sutton, DA (September 2006). "Phialemonium curvatum arthritis of the knee following intra-articular injection of a corticosteroid". Medical Mycology. 44 (6): 571–4. doi: 10.1080/13693780600631883 . PMID 16966177.

- 1 2 3 4 Rivero, M; Hidalgo, A; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A; Cía, M; Torroba, L; Rodríguez-Tudela, JL (November 2009). "Infections due to Phialemonium species: case report and review". Medical Mycology. 47 (7): 766–74. doi: 10.3109/13693780902822800 . PMID 19888810.

- 1 2 3 4 Rao, CY; Pachucki, C; Cali, S; Santhiraj, M; Krankoski, KL; Noble-Wang, JA; Leehey, D; Popli, S; Brandt, ME; Lindsley, MD; Fridkin, SK; Arduino, MJ (September 2009). "Contaminated product water as the source of Phialemonium curvatum bloodstream infection among patients undergoing hemodialysis". Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 30 (9): 840–7. doi:10.1086/605324. PMID 19614543. S2CID 6220912.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Weinberger, M; Mahrshak, I; Keller, N; Goldscmied-Reuven, A; Amariglio, N; Kramer, M; Tobar, A; Samra, Z; Pitlik, SD; Rinaldi, MG; Thompson, E; Sutton, D (May 2006). "Isolated endogenous endophthalmitis due to a sporodochial-forming Phialemonium curvatum acquired through intracavernous autoinjections". Medical Mycology. 44 (3): 253–9. doi: 10.1080/13693780500411097 . PMID 16702105.

- ↑ Egan, Daniel J. "Endophthalmitis". Medscape. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ↑ Freda, R; Dal Pizzol, MM; Fortes Filho, JB (Nov–Dec 2011). "Phialemonium curvatum infection after phacoemulsification: a case report". European Journal of Ophthalmology. 21 (6): 834–6. doi:10.5301/ejo.2011.8360. PMID 21607929. S2CID 37712301.

- 1 2 Zayit-Soudry, S; Neudorfer, M; Barak, A; Loewenstein, A; Bash, E; Siegman-Igra, Y (October 2005). "Endogenous Phialemonium curvatum endophthalmitis". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 140 (4): 755–7. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2005.04.037. PMID 16226540.

- 1 2 Heins-Vaccari, EM; Machado, CM; Saboya, RS; Silva, RL; Dulley, FL; Lacaz, CS; Freitas Leite, RS; Hernandez Arriagada, GL (May–Jun 2001). "Phialemonium curvatum infection after bone marrow transplantation". Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de Sao Paulo. 43 (3): 163–6. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652001000300009 . PMID 11452326.

- 1 2 Persy, B; Vrelust, I; Gadisseur, A; Ieven, M (Sep–Oct 2011). "Phialemonium curvatum fungaemia in an immunocompromised patient: case report". Acta Clinica Belgica. 66 (5): 384–6. doi:10.2143/ACB.66.5.2062593 (inactive 1 November 2024). PMID 22145276.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - 1 2 Sutton, DA; Wickes, BL; Thompson, EH; Rinaldi, MG; Roland, RM; Libal, MC; Russell, K; Gordon, S (June 2008). "Pulmonary Phialemonium curvatum phaeohyphomycosis in a Standard Poodle dog". Medical Mycology. 46 (4): 355–9. doi: 10.1080/13693780701861470 . PMID 18415843.