Sexual selection is a mode of natural selection in which members of one biological sex choose mates of the other sex to mate with, and compete with members of the same sex for access to members of the opposite sex. These two forms of selection mean that some individuals have greater reproductive success than others within a population, for example because they are more attractive or prefer more attractive partners to produce offspring. Successful males benefit from frequent mating and monopolizing access to one or more fertile females. Females can maximise the return on the energy they invest in reproduction by selecting and mating with the best males.

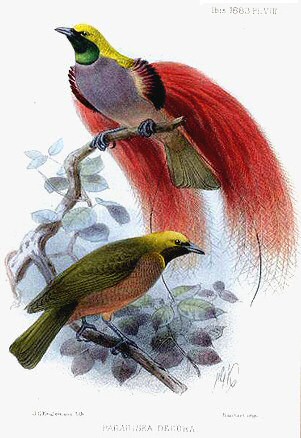

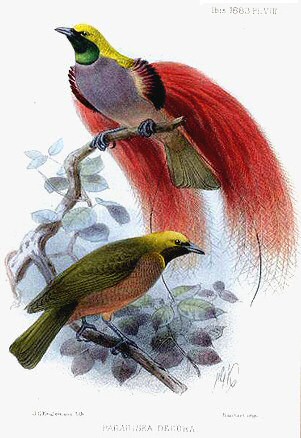

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecious species, which consist of most animals and some plants. Differences may include secondary sex characteristics, size, weight, color, markings, or behavioral or cognitive traits. Male-male reproductive competition has evolved a diverse array of sexually dimorphic traits. Aggressive utility traits such as "battle" teeth and blunt heads reinforced as battering rams are used as weapons in aggressive interactions between rivals. Passive displays such as ornamental feathering or song-calling have also evolved mainly through sexual selection. These differences may be subtle or exaggerated and may be subjected to sexual selection and natural selection. The opposite of dimorphism is monomorphism, when both biological sexes are phenotypically indistinguishable from each other.

Waders or shorebirds are birds of the order Charadriiformes commonly found wading along shorelines and mudflats in order to forage for food crawling or burrowing in the mud and sand, usually small arthropods such as aquatic insects or crustaceans. The term "wader" is used in Europe, while "shorebird" is used in North America, where "wader" may be used instead to refer to long-legged wading birds such as storks and herons.

The Thomisidae are a family of spiders, including about 170 genera and over 2,100 species. The common name crab spider is often linked to species in this family, but is also applied loosely to many other families of spiders. Many members of this family are also known as flower spiders or flower crab spiders.

Hymenopus coronatus is a mantis from the tropical forests of Southeast Asia. It is known by various common names, including walking flower mantis, orchid-blossom mantid and (pink) orchid mantis. It is one of several species known as flower mantids, a reference to their unique physical form and behaviour, which often involves moving with a “swaying” motion, as if being “blown” in the breeze. Several species have evolved to mimic orchid flowers as a hunting and camouflaging strategy, “hiding” themselves in plain view and preying upon pollinating insects that visit the blooms. They are known to grab their prey with blinding speed.

Misumena vatia is a species of crab spider with a holarctic distribution. In North America, it is called the goldenrod crab spider or flower (crab) spider, as it is commonly found hunting in goldenrod sprays and milkweed plants. They are called crab spiders because of their unique ability to walk sideways as well as forwards and backwards. Both males and females of this species progress through several molts before reaching their adult sizes, though females must molt more to reach their larger size. Females can grow up to 10 mm (0.39 in) while males are quite small, reaching 5 mm (0.20 in) at most. Misumena vatia are usually yellow or white or a pattern of these two colors. They may also present with pale green or pink instead of yellow, again, in a pattern with white. They have the ability to change between these colors based on their surroundings through the molting process. They have a complex visual system, with eight eyes, that they rely on for prey capture and for their color-changing abilities. Sometimes, if Misumena vatia consumes colored prey, the spider itself will take on that color.

Gasteracantha fornicata is a species of spiny orb-weavers found in Queensland Australia. It is similar in shape to Austracantha minax which was originally described as Gasteracantha minax. It was described by Johan Christian Fabricius in 1775, the first Australian species of spider to be named and classified.

The brown songlark, also Australian songlark, is a small passerine bird found throughout much of Australia. A member of the family Locustellidae, this species is notable for sexual size dimorphism, among the most pronounced in any bird. It is a moderate-sized bird of nondescript plumage; the female brownish above and paler below, the larger male a darker brown.

Hetaerina is a genus of damselflies in the family Calopterygidae. They are commonly known as rubyspots because of the deep red wing bases of the males. The name is from Ancient Greek: ἑταίρα (hetaira), courtesan. H. rudis, the Guatemalan rubyspot, is considered vulnerable on the IUCN Red Data List.

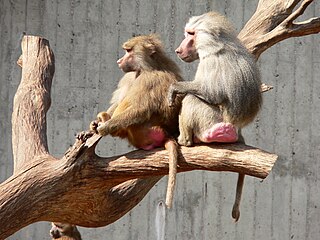

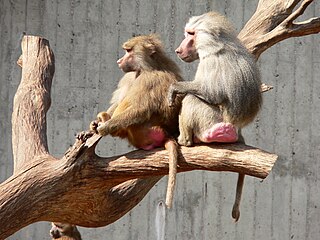

Sexual dimorphism describes the morphological, physiological, and behavioral differences between males and females of the same species. Most primates are sexually dimorphic for different biological characteristics, such as body size, canine tooth size, craniofacial structure, skeletal dimensions, pelage color and markings, and vocalization. However, such sex differences are primarily limited to the anthropoid primates; most of the strepsirrhine primates and tarsiers are monomorphic.

Misumenoides formosipes is a species of crab spiders (Thomisidae), belonging to the genus Misumenoides. The species' unofficial common name is white banded crab spider, which refers to a white line that runs through the plane of their eyes. This species is a sit-and-wait predator that captures pollinators as they visit the inflorescences on which the spider sits. The spider has strong front legs which are used to seize prey. The female spider is much larger than the male. The pattern of markings on females is variable and the overall color of the body can change between white and yellow dependent on the color of their surroundings. The color pattern for males, which does not change in their lifetime, differs from females in that the four front legs of males are darker and the abdomen is gold. The spider can be found throughout the United States. Males search for sedentary females within a heterogeneous habitat and guard them until they are sexually mature to reproduce.

Intralocus sexual conflict is a type of sexual conflict that occurs when a genetic locus harbours alleles which have opposing effects on the fitness of each sex, such that one allele improves the fitness of males, while the alternative allele improves the fitness of females. Such "sexually antagonistic" polymorphisms are ultimately generated by two forces: (i) the divergent reproductive roles of each sex, such as conflicts over optimal mating strategy, and (ii) the shared genome of both sexes, which generates positive between-sex genetic correlations for most traits. In the long term, intralocus sexual conflict is resolved when genetic mechanisms evolve that decouple the between-sex genetic correlations between traits. This can be achieved, for example, via the evolution of sex-biased or sex-limited genes.

Pisaurina mira, also known as the American nursery web spider, is a species of spider in the family Pisauridae. They are often mistaken for wolf spiders (Lycosidae) due to their physical resemblance. P. mira is distinguished by its unique eye arrangement of two rows.

Insect thermoregulation is the process whereby insects maintain body temperatures within certain boundaries. Insects have traditionally been considered as poikilotherms as opposed to being homeothermic. However, the term temperature regulation, or thermoregulation, is currently used to describe the ability of insects and other animals to maintain a stable temperature, at least in a portion of their bodies by physiological or behavioral means. While many insects are ectotherms, others are endotherms. These endothermic insects are better described as regional heterotherms because they are not uniformly endothermic. When heat is being produced, different temperatures are maintained in different parts of their bodies, for example, moths generate heat in their thorax prior to flight but the abdomen remains relatively cool.

Mecaphesa celer, known generally as the swift crab spider, is a species of crab spider in the family Thomisidae. Its range is quite large, and it is found throughout much of North and Central America.

Sexual selection is described as natural selection arising through preference by one sex for certain characteristics in individuals of the other sex. Sexual selection is a common concept in animal evolution but, with plants, it is oftentimes overlooked because many plants are hermaphrodites. Flowering plants show many characteristics that are often sexually selected for. For example, flower symmetry, nectar production, floral structure, and inflorescences are just a few of the many secondary sex characteristics acted upon by sexual selection. Sexual dimorphisms and reproductive organs can also be affected by sexual selection in flowering plants.

Thomisus spectabilis, also known as the white crab spider or Australian crab spider, is a small spider found in Australia and far east Asia.

Forsteropsalis pureora is a species of long-legged harvestman in the family Neopilionidae. This species is endemic to New Zealand, found in the North Island. They are found in native forest, often resting on vegetation or stream banks.

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. Sexual dimorphism in carnivorans, in which males are larger than females, is common among carnivorans. Sexual selection is frequently cited as the cause of the intraspecific divergence in body proportions and craniomandibular morphology between the sexes within the Carnivora order. It is anticipated that animals with polygynous mating systems and high levels of territoriality and solitary behavior will exhibit the highest levels of sexual size dimorphism. Pinnipeds offer an illustration for this.

Maevia intermedia is one of eight species of Salticidae, or jumping spider, in the genus Maevia, and is native to North America. This species was originally reported by American Zoologist Robert D. Barnes in 1955 as a needed distinguishment between the similar-looking Maevia species, especially those found in the Americas.