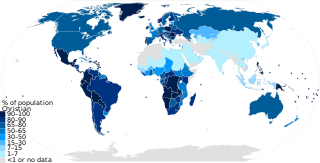

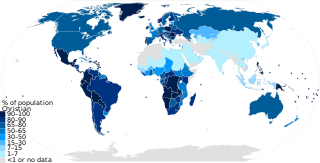

Christendom refers to Christian states, Christian-majority countries or countries in which Christianity is dominant or prevails.

The relationship between religion and science involves discussions that interconnect the study of the natural world, history, philosophy, and theology. Even though the ancient and medieval worlds did not have conceptions resembling the modern understandings of "science" or of "religion", certain elements of modern ideas on the subject recur throughout history. The pair-structured phrases "religion and science" and "science and religion" first emerged in the literature during the 19th century. This coincided with the refining of "science" and of "religion" as distinct concepts in the preceding few centuries—partly due to professionalization of the sciences, the Protestant Reformation, colonization, and globalization. Since then the relationship between science and religion has been characterized in terms of "conflict", "harmony", "complexity", and "mutual independence", among others.

John Charlton Polkinghorne was an English theoretical physicist, theologian, and Anglican priest. A prominent and leading voice explaining the relationship between science and religion, he was professor of mathematical physics at the University of Cambridge from 1968 to 1979, when he resigned his chair to study for the priesthood, becoming an ordained Anglican priest in 1982. He served as the president of Queens' College, Cambridge, from 1988 until 1996.

The perennial philosophy, also referred to as perennialism and perennial wisdom, is a school of thought in philosophy and spirituality that posits that the recurrence of common themes across world religions illuminates universal truths about the nature of reality, humanity, ethics, and consciousness. Some perennialists emphasize common themes in religious experiences and mystical traditions across time and cultures; others argue that religious traditions share a single metaphysical truth or origin from which all esoteric and exoteric knowledge and doctrine have developed.

The relationship between Buddhism and science is a subject of contemporary discussion and debate among Buddhists, scientists, and scholars of Buddhism. Historically, Buddhism encompasses many types of beliefs, traditions and practices, so it is difficult to assert any single "Buddhism" in relation to science. Similarly, the issue of what "science" refers to remains a subject of debate, and there is no single view on this issue. Those who compare science with Buddhism may use "science" to refer to "a method of sober and rational investigation" or may refer to specific scientific theories, methods or technologies.

Christian mysticism is the tradition of mystical practices and mystical theology within Christianity which "concerns the preparation [of the person] for, the consciousness of, and the effect of [...] a direct and transformative presence of God" or divine love. Until the sixth century the practice of what is now called mysticism was referred to by the term contemplatio, c.q. theoria, from contemplatio, "looking at", "gazing at", "being aware of" God or the divine. Christianity took up the use of both the Greek (theoria) and Latin terminology to describe various forms of prayer and the process of coming to know God.

Pascal Robert Boyer is a Franco-American cognitive anthropologist and evolutionary psychologist, mostly known for his work in the cognitive science of religion. He studied at université Paris-Nanterre and Cambridge, and taught at the University of Cambridge for eight years, before taking up the position of Henry Luce Professor of Individual and Collective Memory at Washington University in St. Louis, where he teaches classes on evolutionary psychology and anthropology. He was a Guggenheim Fellow and a visiting professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara and the University of Lyon, France. He studied philosophy and anthropology at University of Paris and Cambridge, with Jack Goody, working on memory constraints on the transmission of oral literature. Boyer is a Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

John Boswell Cobb Jr. is an American theologian, philosopher, and environmentalist. He is often regarded as the preeminent scholar in the field of process philosophy and process theology, the school of thought associated with the philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead. Cobb is the author of more than fifty books. In 2014, Cobb was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

In philosophy, theophysics is an approach to cosmology that attempts to reconcile physical cosmology and religious cosmology. It is related to physicotheology, the difference between them being that the aim of physicotheology is to derive theology from physics, whereas that of theophysics is to unify physics and theology.

Christian Heinrich Arthur Drews was a German writer, historian, philosopher, and important representative of German monist thought. He was born in Uetersen, Holstein, in present-day Germany.

Faith, Science, and Understanding is a book by John Polkinghorne which explores aspects of the integration between science and theology. It is based on lectures he gave at the University of Nottingham and Yale and on some other papers.

Issues in Science and Religion is a book by Ian Barbour. A biography provided by the John Templeton Foundation and published by PBS online states this book "has been credited with literally creating the contemporary field of science and religion."

William Grosvenor Pollard (1911–1989) was an American physicist and an Episcopal priest. He started his career as a professor of physics in 1936 at the University of Tennessee. In 1946 he championed the organization of the Oak Ridge Institute of Nuclear Studies (ORINS). He was its executive director until 1974. He was ordained as a priest in 1954. He authored and co-authored a significant amount of material in the areas of Christianity and Science and Religion found in books, book chapters, and journal articles. He was sometimes referred to as the "atomic deacon".

Karl Heim was a professor of dogmatics at Münster and Tübingen. He retired in 1939. His idea of God controlling quantum events that do and would seem otherwise random has been seen as the precursor to much of the current studies on divine action. His current influence upon religion and science theology has been compared in degree to that of the physicist and theologian Ian Barbour and of the scientist and theological organizer Ralph Wendell Burhoe. His doctrine on the transcendence of God has been thought to anticipate important points of later religious and science discussions, including the application of Thomas Kuhn's idea of a paradigm to religion and Thomas F. Torrance's theory of multileveled knowledge. Mention of Heim's physical and theological concept of extra-dimensional space can be found in a 2001 puzzle book by the popular mathematics writer Martin Gardner. His concept of space has also been discussed by Ian Barbour himself, who in a review of the book Christian Faith and Natural Science and in a mention of "its more technical sequel" The Transformation of the Scientific World-View, found it to be "an illuminating insight."

Spiritual naturalism, or naturalistic spirituality combines a naturalist philosophy with spirituality. Spiritual naturalism may have first been proposed by Joris-Karl Huysmans in 1895 in his book En Route.

Coming into prominence as a writer during the 1870s, Huysmans quickly established himself among a rising group of writers, the so-called Naturalist school, of whom Émile Zola was the acknowledged head...With Là-bas (1891), a novel which reflected the aesthetics of the spiritualist revival and the contemporary interest in the occult, Huysmans formulated for the first time an aesthetic theory which sought to synthesize the mundane and the transcendent: "spiritual Naturalism".

Questions of Truth is a book by John Polkinghorne and Nicholas Beale which offers their responses to 51 questions about science and religion. The foreword is contributed by Antony Hewish.

Christian agnosticism is a theological position drawing influences from Christianity as well as agnosticism. Christian agnostics hold that it is difficult or impossible to be sure of anything beyond the basic tenets of the Christian faith. They believe that God or a higher power might exist, that Jesus may have a special relationship with God, might in some way be divine, and that God might perhaps be worshipped. This belief system has deep roots in the early days of the Church.

Most scientific and technical innovations prior to the Scientific Revolution were achieved by societies organized by religious traditions. Ancient Christian scholars pioneered individual elements of the scientific method. Historically, Christianity has been and still is a patron of sciences. It has been prolific in the foundation of schools, universities and hospitals, and many Christian clergy have been active in the sciences and have made significant contributions to the development of science.