Plains hide painting is a traditional North American Plains Indian artistic practice of painting on either tanned or raw animal hides. Tipis, tipi liners, shields, parfleches, robes, clothing, drums, and winter counts could all be painted.

Plains hide painting is a traditional North American Plains Indian artistic practice of painting on either tanned or raw animal hides. Tipis, tipi liners, shields, parfleches, robes, clothing, drums, and winter counts could all be painted.

Art historian Joyce Szabo writes that Plains artists were concerned "with composition, balance, symmetry, and variety." [1] Designs can be similar to those found in earlier rock art and later quillwork and beadwork.

Plains women traditionally paint abstract, geometric designs. [2] [3] Bright colors were preferred and areas were filled with solid fields of color. Cross-hatching was a last resort used only when paint was scarce. Negative space was important and designs were discussed by women in terms of their negative space. Dots are used to break up large areas. [2]

Buffalo robes and parfleches were frequently painted with geometrical patterns. Parfleches are rawhide envelopes for carrying and storing goods, including food. Their painted designs are thought to be stylized maps, featuring highly abstract geographic features such as rivers or mountains. [4]

The "Feathered Sun" is a reoccurring motif of stylized feathers in several concentric circles. It visually connects a feather warbonnet to the sun. [5]

Traditionally, men painted representational art. [3] [6] They painted living things. [2] Plains Indian male artists use a system of pictographic signs, characterized by two-dimensionality, readily recognizable by other members of their tribe. [7] This picture writing could be used for anything from directions and maps to love letters. Images were streamlined and backgrounds were minimal for clarity. Representational painting typically fell into two categories: heraldic accounts or calendars. [6]

Men recorded their battle and hunting exploits on hide tipi liners, robes, and even shirts. [8] Figures were scattered across the hide and semi-transparent images sometimes overlapped each other. [9] Narrative hides were often read right to left, with the protagonist emerging from the right. [10] Allies are on the right with enemies on the left. [11] Men and horses were commonly painted, and other popular motifs included footprints, hoofprints, name glyphs, bullets, and arrows. An 1868 Blackfoot buffalo hide features the protagonist no fewer than eight times. [12]

Painted hides also commemorate historical events, such as treaty signings.

After 1850, hide painting grew in complexity with finer lines and additional details added. [13] Introduced technologies influenced hide painting, and a 19th-century Omaha tipi featured steamboats. [13]

Traditional Plains calendars are called winter counts because among most Plains tribes they feature a single pictogram that defined the entire year. Prior to using the Gregorian calendar, Lakota people counted years from first snow to first snow. Kiowas were unique in choosing two images per year– one for the winter and one representing the summer Sun Dance. [14]

Before the late 19th century when buffalo became scarce, winter counts were painted in buffalo hides. The annual pictograms could be arranged in a linear, spiral, or serpentine pattern. [15]

Visions and dreams could inspire designs. Buckskin covers for circular rawhide hide shields, in particular, are inspired by men's visions and can include paintings of humans, animals, or spirit beings, reflecting the owner's personal powers and providing protection. [2] [16] Designs could be obtained from the warriors who received the visions or from medicine men. Cheyenne men who received visions were allowed to make four shields with the design. Among the Kiowa and Kiowa-Apache about 50 possible shield designs existed. [17]

Tipis could be painted with visionary designs. The design and related power belonged to the tipi-owner, which could be transferred by inheritance, marriage, or, among some tribes such as the Blackfeet, sale. [17]

Followers of the Ghost dance religion painted visionary designs on their clothing. Arapaho and Lakota ghost dance shirts were painted with crows, magpies, turtles, and cedar trees. [16]

Buffalo hides, as well as deer, elk, and other animal hides, are painted. Clothing and robes are often brain-tanned to be soft and supple. Parfleches, shields, and moccasin soles are rawhide for toughness.

In the past, Plains artists used a bone or wood stylus to paint with natural mineral and vegetable pigments. Sections of buffalo rib could be ground to expose the marrow, which was absorbent and worked like a contemporary ink marker. [18] Swelling cottonwood buds provided brown pigment. [19] Lakota artists used to burn yellow clay to produce ceremonial red paint. Lakotas associated blue pigments with women. [20]

In earlier times, all members of a tribe might paint but highly skilled individuals might be commissioned by others to create artwork. [17] Before the 20th century, when a Kiowa man needed to repaint his lodge, he would invite 20-30 friends to paint the entire tipi in a single day. He would then treat them all to a feast. [6]

Many tribes throughout North America, besides those on the Plains, also painted hides, following different aesthetic traditions. Subarctic tribes are known for their painted caribou hides. On the Plains, when buffalo herds were being slaughtered in the late 19th century, other painting surfaces became available, such as muslin, paper, and canvas, giving birth to Ledger art. [21] Contemporary Plains beadwork and jewelry used designs from hide painting. [22]

The Crow, whose autonym is Apsáalooke, also spelled Absaroka, are Native Americans living primarily in southern Montana. Today, the Crow people have a federally recognized tribe, the Crow Tribe of Montana, with an Indian reservation, the Crow Indian Reservation, located in the south-central part of the state.

The Comanche or Nʉmʉnʉʉ is a Native American tribe from the Southern Plains of the present-day United States. Comanche people today belong to the federally recognized Comanche Nation, headquartered in Lawton, Oklahoma.

The Blackfoot Confederacy, Niitsitapi, or Siksikaitsitapi, is a historic collective name for linguistically related groups that make up the Blackfoot or Blackfeet people: the Siksika ("Blackfoot"), the Kainai or Blood, and two sections of the Peigan or Piikani – the Northern Piikani (Aapátohsipikáni) and the Southern Piikani. Broader definitions include groups such as the Tsúùtínà (Sarcee) and A'aninin who spoke quite different languages but allied with or joined the Blackfoot Confederacy.

A tipi or tepee is a conical lodge tent that is distinguished from other conical tents by the smoke flaps at the top of the structure, and historically made of animal hides or pelts or, in more recent generations, of canvas stretched on a framework of wooden poles. The loanword came into English usage from the Dakota and Lakota languages.

Kiowa or CáuigúIPA:[kɔ́j-gʷú]) people are a Native American tribe and an Indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries, and eventually into the Southern Plains by the early 19th century. In 1867, the Kiowa were moved to a reservation in southwestern Oklahoma.

Plains Indians or Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies are the Native American tribes and First Nation band governments who have historically lived on the Interior Plains of North America. While hunting-farming cultures have lived on the Great Plains for centuries prior to European contact, the region is known for the horse cultures that flourished from the 17th century through the late 19th century. Their historic nomadism and armed resistance to domination by the government and military forces of Canada and the United States have made the Plains Indian culture groups an archetype in literature and art for Native Americans everywhere.

Winter counts are pictorial calendars or histories in which tribal records and events were recorded by Native Americans in North America. The Blackfeet, Mandan, Kiowa, Lakota, and other Plains tribes used winter counts extensively. There are approximately one hundred winter counts in existence, many of which are duplicates.

Quillwork is a form of textile embellishment traditionally practiced by Indigenous peoples of North America that employs the quills of porcupines as an aesthetic element. Quills from bird feathers were also occasionally used in quillwork.

A parfleche is a Native American rawhide container that is embellished by painting, incising, or both.

The plains bison is one of two subspecies/ecotypes of the American bison, the other being the wood bison. A natural population of plains bison survives in Yellowstone National Park and multiple smaller reintroduced herds of bison in many places in the United States as well as southern portions of the Canadian Prairies.

A hair drop is an ornament worn by men from Great Lakes and Plains tribes. It would be tied to the man's hair. The typical example consists of a quilled or beaded section on a strip of leather, which was later attached to an American buffalo tail. They could be over two feet long.

The Fort Belknap Indian Reservation is shared by two Native American tribes, the A'aninin and the Nakoda (Assiniboine). The reservation covers 1,014 sq mi (2,630 km2), and is located in north-central Montana. The total area includes the main portion of their homeland and off-reservation trust land. The tribes reported 2,851 enrolled members in 2010. The capital and largest community is Fort Belknap Agency, at the reservation's north end, just south of the city of Harlem, Montana, across the Milk River.

The visual arts of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas encompasses the visual artistic practices of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas from ancient times to the present. These include works from South America and North America, which includes Central America and Greenland. The Siberian Yupiit, who have great cultural overlap with Native Alaskan Yupiit, are also included.

Ledger art is narrative drawing or painting on paper or cloth, predominantly practiced by Plains Indian, but also from the Plateau and Great Basin. Ledger art flourished primarily from the 1860s to the 1920s. A revival of ledger art began in the 1960s and 1970s. The term comes from the accounting ledger books that were a common source of paper for Plains Indians during the late 19th century.

The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes are a united, federally recognized tribe of Southern Arapaho and Southern Cheyenne people in western Oklahoma.

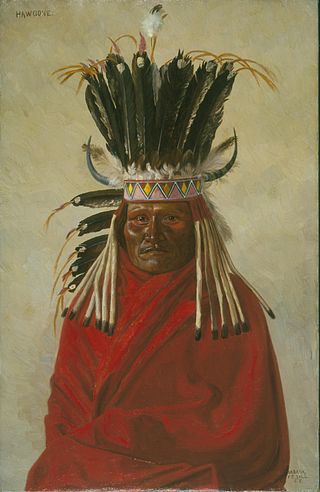

Silver Horn or Haungooah (1860–1940) was a Kiowa ledger artist from Oklahoma.

Lois Smoky Kaulaity (1907–1981) was a Kiowa beadwork artist and a painter, one of the Kiowa Six, from Oklahoma.

Bison hunting was an activity fundamental to the economy and society of the Plains Indians peoples who inhabited the vast grasslands on the Interior Plains of North America, before the animal's near-extinction in the late 19th century following US expansion into the West. Bison hunting was an important spiritual practice and source of material for these groups, especially after the European introduction of the horse in the 16th through 19th centuries enabled new hunting techniques. The species' dramatic decline was the result of habitat loss due to the expansion of ranching and farming in western North America, industrial-scale hunting practiced by non-Indigenous hunters increased Indigenous hunting pressure due to non-Indigenous demand for bison hides and meat, and cases of a deliberate policy by settler governments to destroy the food source of the Indigenous peoples during times of conflict.

A buffalo robe is a cured buffalo hide, with the hair left on.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the prehistoric people of Colorado, which covers the period of when Native Americans lived in Colorado prior to contact with the Domínguez–Escalante expedition in 1776. People's lifestyles included nomadic hunter-gathering, semi-permanent village dwelling, and residing in pueblos.