Quillwork is a form of textile embellishment traditionally practiced by Indigenous peoples of North America that employs the quills of porcupines as an aesthetic element. Quills from bird feathers were also occasionally used in quillwork.

Quillwork is a form of textile embellishment traditionally practiced by Indigenous peoples of North America that employs the quills of porcupines as an aesthetic element. Quills from bird feathers were also occasionally used in quillwork.

Porcupine quillwork is an art form unique to North America. Before the introduction of glass beads, quillwork was a major decorative element used by the peoples who resided in the porcupine's natural habitat, [1] which included indigenous peoples of the Subarctic, Northeastern Woodlands, and Northern Plains. The use of quills in designs spans from Maine to Alaska. [2] Quillworking tools were discovered in Alberta, Canada and date back to the 6th century CE. [3]

Cheyenne oral history, as told by Picking Bones Woman to George Bird Grinnell, says quilling came to their tribe from a man who married a woman, who hid her true identity as a buffalo. His son was also a buffalo. The man visited his wife and son in their buffalo home and while among the buffalo, the man learned the art of quilling, which he shared with the women of his tribe. [4] The crafting society of the highest esteem was the Quilling Society. The quillers were a select group of elite women. [5] Joining the Cheyenne Quilling Society was a prestigious honor for Cheyenne women. The Cheyenne believe that the highest virtue and aspiration is the seeking of knowledge. Their main spirit or deity is Heammawihio (The Wise One Above) who possesses his power through wisdom. All spirits gain power through their knowledge and their ability to share it with the people. [5] [6] The rituals of the crafting societies are structured with a mentor instructing an apprentice in the skills of the craft. The process and ritual that accompanied the production of these crafts (especially quilled crafts) constituted a ceremony of sacred significance. [6] [7] [8] [9] In this way the crafting societies added the additional element of acquired knowledge and experience, which the Cheyenne highly regarded and considered sacred. This would create a system where the people are seeking to possess a piece of the knowledge and skill of the crafter in tangible terms, and this creates a heightened value on the imagery itself. The craft is their act of knowledge seeking, and as such, was a sacred act. In this way, the women with more experience gained greater status in the crafting society. [5] [6] The master and apprentice roles were always present in the crafting societies, as the older women would always have more knowledge due to their lifetime of dedication to the craft. Upon entering the Society, women would work first on quilling moccasins, then cradleboards, rosettes for men's shirts and tipis, and ultimately, hide robes and backrests. [4]

The Blackfoot Native American tribe in the Northwest region of North America also put much significance on women who did quillwork. For the Blackfoot, women doing Quillwork had a religious purpose to it such as wearing special face paint that consisted of yellow ochre and animal fat which would be mixed in the palm of one's hand and then a 'V' marking would be made across the forehead to the nose; This face paint was meant to protect the women who was participating in quillwork and would always be done before doing so. Red paint would then be used to draw a vertical line from the bridge of the nose to the forehead and altogether this would resemble the foot of a crow. They would also wear sacred necklaces each time they did quillwork as another form of protection. [10] When a woman would become too old to continue her craft she would have a younger woman become an initiate, generally a relative, so that the craft could be passed on. Being a woman who made quillwork in the Blackfoot tribe held major importance as the few women who did quillwork would choose who would become the next to assume the craft of quillwork. After being initiated, the young woman would be expected to craft a moccasin and would then take it and place it on top of a hill as a form of offering to the sun. [11]

The Arapaho and Odawa tribes also had religious significance for women in Quillwork as their works would represent sacred beings and connections to nature. Colors and shapes also had unique meanings allowing for diverse and unique designs carrying many cultural or religious meanings. [12] The Odawa tribe in particular used many of the same colors as the Blackfoot tribe with the addition of white, yellow, purple, and gold. [13]

Porcupine quills often adorned rawhide and tanned hides, but during the 19th century, quilled birch bark boxes were a popular trade item to sell to European-Americans among Eastern and Great Lakes tribes. Quillwork was used to create and decorate a variety of Native American items, including those of daily usage to Native American men and women. These include clothing such as coats and moccasins, accessories such as bags and belts, and furniture attachments such as a cradle cover. [14]

Quills suitable for embellishment are two to three inches long and may be dyed before use. [1] In their natural state, the quills are pale yellow to white with black tips. The tips are usually snipped off before use. Quills readily take dye, which originally was derived from local plants and included a wide spectrum of colors, with black, yellow, and red being the most common. By the 19th century, aniline dyes were available through trade and made dying easier. [15]

The quills can be flattened with specific bone tools or by being run through one's teeth. Awls were used to punch holes in hides, and sinew, later replaced by European thread, was used to bind the quills to the hides.

The four most common techniques for quillwork are appliqué, embroidery, wrapping, and loom weaving. [16] Appliquéd quills are stitched into hide in a manner that covers the stitches. [1] In wrapping, a single quill may be wrapped upon itself or two quills may be intertwined. [1]

Quills can be appliquéd singly to form curvilinear patterns, as found on Odawa pouches from the 18th century. [17] This technique lends itself to floral designs popularized among northeastern tribes by Ursuline nuns. Huron women excelled at floral quillwork during the 18th and 19th centuries. [18]

Plains quillwork is characterized by bands of rectangles creating geometrical patterns found also in Plains painting. [19] Rosettes of concentric circles of quillwork commonly adorned historical Plains men's shirts, as did parallel panels of quillwork on the sleeves. These highly abstracted designs had layers of symbolic meaning.

The Red River Ojibwe of Manitoba created crisp, geometric patterns by weaving quills on a loom in the 19th century. [20]

Quillwork never died out as a living art form in the Northern Plains. Some communities that had lost their quillwork tradition have been able to revive the art form. For instance, no women quilled in the Dene community of Wha Ti, Northwest Territories by the late 1990s. The Dene Cultural Institute held two workshops there in 1999 and 2000, effectively reviving quillwork in Wha Ti. [21]

The art form is very much alive today. Examples of contemporary, award-winning quillworkers include Juanita Growing Thunder Fogarty, (Sioux-Assiniboine) artist; [22] Dorothy Brave Eagle (Oglala Lakota) of Denver, Colorado; [23] Kanatiiosh (Akwesasne Mohawk) of St. Regis Mohawk Reservation; [24] [25] Sarah Hardisty (Dene) of Jean Marie River, Northwest Territories; [26] Leonda Fast Buffalo Horse (Blackfeet) of Browning, Montana;, [27] Melissa Peter-Paul, Mi'kmaw of Epekwitk/Prince Edward Island, and Deborah Magee Sherer (Blackfeet) of Cut Bank, Montana. [28]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

The Crow, whose autonym is Apsáalooke, also spelled Absaroka, are Native Americans living primarily in southern Montana. Today, the Crow people have a federally recognized tribe, the Crow Tribe of Montana, with an Indian reservation, the Crow Indian Reservation, located in the south-central part of the state.

The Piegan are an Algonquian-speaking people from the North American Great Plains. They are the largest of three Blackfoot-speaking groups that make up the Blackfoot Confederacy; the Siksika and Kainai are the others. The Piegan dominated much of the northern Great Plains during the nineteenth century.

The Cheyenne are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. The Cheyenne comprise two Native American tribes, the Só'taeo'o or Só'taétaneo'o and the Tsétsėhéstȧhese ; the tribes merged in the early 19th century. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enrolled in the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes in Oklahoma, and the Northern Cheyenne, who are enrolled in the Northern Cheyenne Tribe of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in Montana. The Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family.

The Blackfeet are a tribe of Native Americans who currently live in Montana and Alberta. They lived northwest of the Great Lakes and came to participate in Plains Indian culture.

The Blackfoot Confederacy, Niitsitapi, or Siksikaitsitapi, is a historic collective name for linguistically related groups that make up the Blackfoot or Blackfeet people: the Siksika ("Blackfoot"), the Kainai or Blood, and two sections of the Peigan or Piikani – the Northern Piikani (Aapátohsipikáni) and the Southern Piikani. Broader definitions include groups such as the Tsúùtínà (Sarcee) and A'aninin who spoke quite different languages but allied with or joined the Blackfoot Confederacy.

A tipi or tepee is a conical lodge tent that is distinguished from other conical tents by the smoke flaps at the top of the structure, and historically made of animal hides or pelts or, in more recent generations, of canvas stretched on a framework of wooden poles. The loanword came into English usage from the Dakota and Lakota languages.

Kiowa or CáuigúIPA:[kɔ́j-gʷú]) people are a Native American tribe and an Indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries, and eventually into the Southern Plains by the early 19th century. In 1867, the Kiowa were moved to a reservation in southwestern Oklahoma.

Plains Indians or Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies are the Native American tribes and First Nation band governments who have historically lived on the Interior Plains of North America. While hunting-farming cultures have lived on the Great Plains for centuries prior to European contact, the region is known for the horse cultures that flourished from the 17th century through the late 19th century. Their historic nomadism and armed resistance to domination by the government and military forces of Canada and the United States have made the Plains Indian culture groups an archetype in literature and art for Native Americans everywhere.

A parfleche is a Native American rawhide container that is embellished by painting, incising, or both.

George Bird Grinnell was an American anthropologist, historian, naturalist, and writer. Originally specializing in zoology, he became a prominent early conservationist and student of Native American life. Grinnell has been recognized for his influence on public opinion and work on legislation to preserve the American bison. Mount Grinnell in Glacier National Park in Montana is named after him.

A hair drop is an ornament worn by men from Great Lakes and Plains tribes. It would be tied to the man's hair. The typical example consists of a quilled or beaded section on a strip of leather, which was later attached to an American buffalo tail. They could be over two feet long.

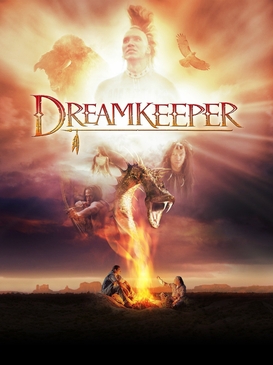

Dreamkeeper is a 2003 film written by John Fusco and directed by Steve Barron. The main plot of the film is the conflict between a Lakota elder and storyteller named Pete Chasing Horse and his Lakota grandson, Shane Chasing Horse.

Ledger art is narrative drawing or painting on paper or cloth, predominantly practiced by Plains Indian, but also from the Plateau and Great Basin. Ledger art flourished primarily from the 1860s to the 1920s. A revival of ledger art began in the 1960s and 1970s. The term comes from the accounting ledger books that were a common source of paper for Plains Indians during the late 19th century.

Juanita Growing Thunder Fogarty is a Native American, Assiniboine Sioux bead worker and porcupine quill worker. She creates traditional Northern Plains regalia.

Teri Greeves is a Native American beadwork artist, living in Santa Fe, New Mexico. She is enrolled in the Kiowa Indian Tribe of Oklahoma.

Plains hide painting is a traditional North American Plains Indian artistic practice of painting on either tanned or raw animal hides. Tipis, tipi liners, shields, parfleches, robes, clothing, drums, and winter counts could all be painted.

The Iron Confederacy or Iron Confederation was a political and military alliance of Plains Indians of what is now Western Canada and the northern United States. This confederacy included various individual bands that formed political, hunting and military alliances in defense against common enemies. The ethnic groups that made up the Confederacy were the branches of the Cree that moved onto the Great Plains around 1740, the Saulteaux, the Nakoda or Stoney people also called Pwat or Assiniboine, and the Métis and Haudenosaunee. The Confederacy rose to predominance on the northern Plains during the height of the North American fur trade when they operated as middlemen controlling the flow of European goods, particularly guns and ammunition, to other Indigenous nations, and the flow of furs to the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) and North West Company (NWC) trading posts. Its peoples later also played a major part in the bison (buffalo) hunt, and the pemmican trade. The decline of the fur trade and the collapse of the bison herds sapped the power of the Confederacy after the 1860s, and it could no longer act as a barrier to U.S. and Canadian expansion.

Alice Blue Legs was a Lakota Sioux craftworker, notable for her quillwork. She received a 1985 National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts and was a featured artist for the documentary film Lakota Quillwork—Art and Legend. Her work was seen in the epic film Dances with Wolves and exhibited in museums such as The Children's Museum of Indianapolis, the Heard Museum, the Sioux Indian Museum. Examples of her work are in the permanent collection of the Indian Arts and Crafts Board at the Washington, D. C. headquarters of the United States Department of the Interior and the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian.

Yvonne Walker Keshick is an Anishinaabe quillwork artist and basket maker.

Mountain Chief was a South Piegan warrior of the Blackfoot Tribe. Mountain Chief was also called Big Brave (Omach-katsi) and adopted the name Frank Mountain Chief. Mountain Chief was involved in the 1870 Marias Massacre, signed the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868, and worked with anthropologist Frances Densmore to interpret folksong recordings.