Embroidery is the art of decorating fabric or other materials using a needle to stitch thread or yarn. Embroidery may also incorporate other materials such as pearls, beads, quills, and sequins. In modern days, embroidery is usually seen on hats, clothing, blankets, and handbags. Embroidery is available in a wide variety of thread or yarn colour. It is often used to personalize gifts or clothing items.

A needlework sampler is a piece of embroidery or cross-stitching produced as a 'specimen of achievement', demonstration or a test of skill in needlework. It often includes the alphabet, figures, motifs, decorative borders and sometimes the name of the person who embroidered it and the date. The word sampler is derived from the Latin exemplum, which means 'example'.

Assisi embroidery is a form of counted-thread embroidery based on an ancient Italian needlework tradition in which the background is filled with embroidery stitches and the main motifs are outlined but not stitched. The name is derived from the Italian town of Assisi where the modern form of the craft originated.

Blackwork, sometimes historically termed Spanish blackwork, is a form of embroidery generally worked in black thread, although other colours are also used on occasion, as in scarletwork, where the embroidery is worked in red thread. Most strongly associated with Tudor period England, blackwork typically, though not always, takes the form of a counted-thread embroidery, where the warp and weft yarns of a fabric are counted for the length of each stitch, producing uniform-length stitches and a precise pattern on an even-weave fabric. Blackwork may also take the form of free-stitch embroidery, where the yarns of a fabric are not counted while sewing.

Hardanger embroidery or "Hardangersøm" is a form of embroidery traditionally worked with white thread on white even-weave linen or cloth, using counted thread and drawn thread work techniques. It is sometimes called whitework embroidery.

Drawn thread work is one of the earliest forms of open work embroidery, and has been worked throughout Europe. Originally it was often used for ecclesiastical items and to ornament shrouds. It is a form of counted-thread embroidery based on removing threads from the warp and/or the weft of a piece of even-weave fabric. The remaining threads are grouped or bundled together into a variety of patterns. The more elaborate styles of drawn thread work use a variety of other stitches and techniques, but the drawn thread parts are their most distinctive element. It is also grouped with whitework embroidery because it was traditionally done in white thread on white fabric and is often combined with other whitework techniques.

Berlin wool work is a style of embroidery similar to today's needlepoint that was particularly popular in Europe and America from 1804 to 1875. It is typically executed with wool yarn on canvas, worked in a single stitch such as cross stitch or tent stitch, although Beeton's book of Needlework (1870) describes 15 different stitches for use in Berlin work. It was traditionally stitched in many colours and hues, producing intricate three-dimensional looks by careful shading. Silk or beads were frequently used as highlights. The design of such embroidery was made possible by the great progress made in dyeing, initially with new mordants and chemical dyes, followed in 1856, especially by the discovery of aniline dyes, which produced bright colors.

Needlepoint is a type of canvas work, a form of embroidery in which yarn is stitched through a stiff open weave canvas. Traditionally needlepoint designs completely cover the canvas. Although needlepoint may be worked in a variety of stitches, many needlepoint designs use only a simple tent stitch and rely upon color changes in the yarn to construct the pattern. Needlepoint is the oldest form of canvas work.

Chain stitch is a sewing and embroidery technique in which a series of looped stitches form a chain-like pattern. Chain stitch is an ancient craft – examples of surviving Chinese chain stitch embroidery worked in silk thread have been dated to the Warring States period. Handmade chain stitch embroidery does not require that the needle pass through more than one layer of fabric. For this reason the stitch is an effective surface embellishment near seams on finished fabric. Because chain stitches can form flowing, curved lines, they are used in many surface embroidery styles that mimic "drawing" in thread.

Jacobean embroidery refers to embroidery styles that flourished in the reign of King James I of England in first quarter of the 17th century.

Embroidery in India includes dozens of embroidery styles that vary by region and clothing styles. Designs in Indian embroidery are formed on the basis of the texture and the design of the fabric and the stitch. The dot and the alternate dot, the circle, the square, the triangle, and permutations and combinations of these constitute the design.

Cutwork or cut work, also known as punto tagliato in Italian, is a needlework technique in which portions of a textile, typically cotton or linen, are cut away and the resulting "hole" is reinforced and filled with embroidery or needle lace.

Embroidery thread is yarn that is manufactured or hand-spun specifically for embroidery and other forms of needlework. Embroidery thread often differs widely, coming in many different fiber types, colors and weights.

In needlework, a slip is a design representing a cutting or specimen of a plant, usually with flowers or fruit and leaves on a stem. Most often, slip refers to a plant design stitched in canvaswork (pettipoint), cut out, and applied to a woven background fabric. By extension, slip may also mean any embroidered or canvaswork motif, floral or not, mounted to fabric in this way.

English embroidery includes embroidery worked in England or by English people abroad from Anglo-Saxon times to the present day. The oldest surviving English embroideries include items from the early 10th century preserved in Durham Cathedral and the 11th century Bayeux Tapestry, if it was worked in England. The professional workshops of Medieval England created rich embroidery in metal thread and silk for ecclesiastical and secular uses. This style was called Opus Anglicanum or "English work", and was famous throughout Europe.

The term Hedebo embroidery covers several forms of white embroidery which originated in the Hedebo (heathland) region of Zealand, Denmark, in the 1760s. The varied techniques which evolved over the next hundred years in the farming community were subsequently developed by the middle classes until around 1820. They were applied to articles of clothing such as collars and cuffs but were also used to decorate bed linen.

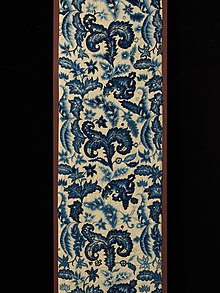

The Deerfield Society of Blue and White Needlework was founded in Deerfield, Massachusetts, in 1896 by Margaret C. Whiting and Ellen Miller. They formed the society in 1896 as a way to help residents boost the town's economy by reviving American needlework from the 1700s. It was inspired by the crewel embroidery of 18th-century women who had lived in the Deerfield, Massachusetts, area. Members of the Blue and White Society initially used the patterns and stitches from these earlier works, but because these new embroideries were not meant to replicate the earlier works, the embroidery soon deviated from the original versions with new patterns and stitches, and even the use of linen, rather than wool, thread. The society disbanded in 1926 for several reasons. Ellen Miller was in declining health; the trained stitchers were getting old and could not continue; Margaret C. Whiting's sight was fading; and, the design and quality of commercially produced items was increasing.

Bed hangings or bed curtains are fabric panels that surround a bed; they were used from medieval times through to the 19th century. Bed hangings provided privacy when the master or great bed was in a public room, such as the parlor, but also showed evidence of wealth when beds were located in areas of the home where. They also kept warmth in, and were a way of showing one's wealth. When bedrooms became more common in the mid-1700s, the use of bed hangings diminished.

Colcha embroidery from the southwest United States is a form of surface embroidery that uses wool threads on cotton or linen fabric. During the Spanish Colonial period, the word colcha referred to a densely embroidered wool coverlet. In time, the word also came to refer to the embroidery stitch that was used for these coverlets, and then began to be used on other surfaces. The colcha stitch is self-couched, with threads applied at a 45-degree angle to tie down the stitch. Originally, the wool threads were dyed naturally, using plants or insects, such as cochineal. Both materials used and design motifs have varied over time.

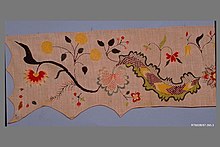

Bed rugs are heavy, embroidered bed covers made primarily in the United States from the mid 1600s through the early 1800s. The earliest were made in eastern Massachusetts, though many have been found in the Connecticut River Valley. They involve wool stitching on either wool or linen backings. They differ from other embroidered coverlets in that bed rugs embroidery covered the background fabric, and in many cases the looped stitches were cut to form pile.