Anishinaabe traditional beliefs cover the traditional belief system of the Anishinaabeg peoples, consisting of the Algonquin/Nipissing, Ojibwa/Chippewa/Saulteaux/Mississaugas, Odawa, Potawatomi and Oji-Cree, located primarily in the Great Lakes region of North America.

The Ojibwe are an Anishinaabe people whose homeland covers much of the Great Lakes region and the northern plains, extending into the subarctic and throughout the northeastern woodlands. The Ojibwe, being Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands and of the subarctic, are known by several names, including Ojibway or Chippewa. As a large ethnic group, several distinct nations also consider themselves Ojibwe, including the Saulteaux, Nipissings, and Oji-Cree.

Ojibwe, also known as Ojibwa, Ojibway, Otchipwe, Ojibwemowin, or Anishinaabemowin, is an indigenous language of North America of the Algonquian language family. The language is characterized by a series of dialects that have local names and frequently local writing systems. There is no single dialect that is considered the most prestigious or most prominent, and no standard writing system that covers all dialects.

The Council of Three Fires is a long-standing Anishinaabe alliance of the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi North American Native tribes.

The Red Lake Indian Reservation covers 1,260.3 sq mi in parts of nine counties in Minnesota, United States. It is made up of numerous holdings but the largest section is an area around Red Lake, in north-central Minnesota, the largest lake in the state. This section lies primarily in the counties of Beltrami and Clearwater. Land in seven other counties is also part of the reservation. The reservation population was 5,506 in the 2020 census.

The Anishinaabe are a group of culturally related Indigenous peoples in the Great Lakes region of Canada and the United States. They include the Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi, Mississaugas, Nipissing, and Algonquin peoples. The Anishinaabe speak Anishinaabemowin, or Anishinaabe languages that belong to the Algonquian language family.

The Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, commonly shortened to Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians or the more colloquial Soo Tribe, is a federally recognized Native American tribe in what is now known as Michigan's Upper Peninsula. The tribal headquarters is located within Sault Ste. Marie, the major city in the region, which is located on the St. Marys River.

Saugeen First Nation is an Ojibway First Nation band located along the Saugeen River and Bruce Peninsula in Ontario, Canada. The band states that their legal name is the "Chippewas of Saugeen". Organized in the mid-1970s, Saugeen First Nation is the primary "political successor apparent" to the Chippewas of Saugeen Ojibway Territory; the other First Nation that is a part of Chippewas of Saugeen Ojibway Territory is Cape Croker. The Ojibway are of the Algonquian languages family. The First Nation consist of four reserves: Chief's Point 28, Saugeen 29, Saugeen Hunting Grounds 60A, and Saugeen and Cape Croker Fishing Islands 1.

Gitche Manitou means "Great Spirit" in several Algonquian languages. Christian missionaries have translated God as Gitche Manitou in scriptures and prayers in the Algonquian languages.

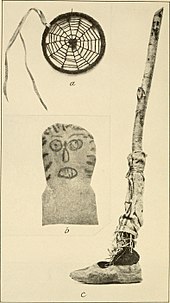

Cradleboards are traditional protective baby-carriers used by many indigenous cultures in North America, throughout northern Scandinavia among the Sámi, and in the traditionally nomadic cultures of Central Asia. There is a variety of styles of cradleboard, reflecting the diverse artisan practices of indigenous cultures. Many Central Asian communities and some indigenous communities in North America still use cradleboards.

A wiigwaasabak is a birch bark scroll, on which the Ojibwa (Anishinaabe) people of North America wrote with a written language composed of complex geometrical patterns and shapes.

Frances Theresa Densmore was an American anthropologist and ethnographer born in Red Wing, Minnesota. Densmore studied Native American music and culture, and in modern terms, she may be described as an ethnomusicologist.

Chequamegon Bay is an inlet of Lake Superior in Ashland and Bayfield counties in the extreme northern part of Wisconsin.

Spider Grandmother is an important figure in the mythology, oral traditions and folklore of many Native American cultures, especially in the Southwestern United States.

The Saugeen Ojibway Nation Territory, also known as Saugeen Ojibway Nation, SON and the Chippewas of Saugeen Ojibway Territory, is the name applied to Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation and Saugeen First Nation as a collective, represented by a joint council. The collective First Nations are Ojibway (Anishinaabe) peoples located on the eastern shores of Lake Huron on the Bruce Peninsula in Ontario, Canada. Though predominantly Ojibway, due to large influx of refugees from the south and west after the War of 1812, the descendants of the Chippewas of Saugeen Ojibway Territory also have ancestry traced to Odawa and Potawatomi peoples.

Woodlands style, also called the Woodlands school, Legend painting, Medicine painting, and Anishnabe painting, is a genre of painting among First Nations and Native American artists from the Great Lakes area, including northern Ontario and southwestern Manitoba. The majority of the Woodlands artists are Anishinaabeg, notably the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi, as well as the Oji-Cree and the Cree.

Little River Band of Ottawa Indians is a federally recognized Native American tribe of the Odawa people in the United States. It is based in Manistee and Mason counties in northwest Michigan. It was recognized on September 21, 1994.

Kinnikinnick is a Native American and First Nations herbal smoking mixture, made from a traditional combination of leaves or barks. Recipes for the mixture vary, as do the uses, from social, to spiritual to medicinal.

A wiigwaasi-makak, meaning "birch-bark box" in the Anishinaabe language, is a box made of panels of birchbark sewn together with watap. The construction of makakoon from birchbark was an essential element in the culture of the Anishinaabe people and other members of the Native Americans and First Nations of the Upper Great Lakes, particularly in the regions surrounding Lake Superior. Birchbark makakoon continue to be crafted to this day as heritage heirlooms and for the tourist trade.

Patrick William Kruse, also known as Pat Kruse, is a Native American culture teacher and artist that specializes in birchbark art and quillwork. He works alongside his son Gage to create birch bark paintings.