Via Rail Canada Inc., operating as Via Rail or Via, is a Canadian Crown corporation that operates intercity passenger rail service in Canada.

The Summit Tunnel fire occurred on 20 December 1984, when a dangerous goods train caught fire while passing through the Summit Tunnel on the railway line between Littleborough and Todmorden on the Greater Manchester/West Yorkshire border, England.

The town of Morpeth in Northumberland, England, has what is reputed to be the tightest curve of any main railway line in Britain. The track turns approximately 98° from a northwesterly to an easterly direction immediately west of Morpeth Station on an otherwise fast section of the East Coast Main Line railway. This was a major factor in three serious derailments between 1969 and 1994. The curve has a permanent speed restriction of 50 miles per hour (80 km/h).

On February 8, 1986, 23 people were killed in a collision between a Canadian National Railway freight train and a Via Rail passenger train called the Super Continental, including the engine crews of both trains. It was the deadliest rail disaster in Canada since the Dugald accident of 1947, which had 31 fatalities, and was not surpassed until the Lac-Mégantic rail disaster in 2013, which resulted in 47 deaths.

The Norton Fitzwarren rail crash occurred on 4 November 1940 between Taunton and Norton Fitzwarren in the English county of Somerset, when the driver of a train misunderstood the signalling and track layout, causing him to drive the train through a set of points and off the rails at approximately 40 miles per hour (64 km/h). 27 people were killed. The locomotive involved was GWR King Class GWR 6028 King Class King George VI which was subsequently repaired and returned to service. A previous significant accident occurred here on 10 November 1890 and the Taunton train fire of 1978 was also within 2 metres.

Hudson Bay Railway is a Canadian short line railway operating over 1,300 kilometres (810 mi) of track in northeastern Saskatchewan and northern Manitoba.

Montana Rail Link was a privately held Class II railroad in the United States. It operated on trackage originally built by the Northern Pacific Railway and leased from its successor BNSF Railway. MRL was a unit of The Washington Companies and was headquartered in Missoula, Montana.

The Waverly, Tennessee tank car explosion killed 16 people and injured 43 others on February 24, 1978, in Waverly, Tennessee. Following a train derailment a two days earlier, a cleanup crew had been sent into the area. At approximately 2:58 in the afternoon, a tank car containing 30,161 US gallons of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) exploded after an action taken during the cleanup related to the derailment.

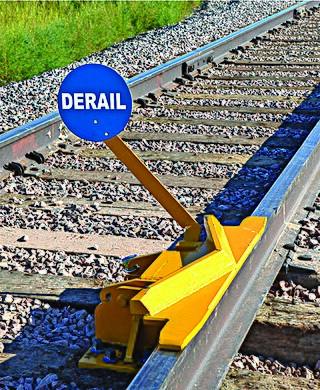

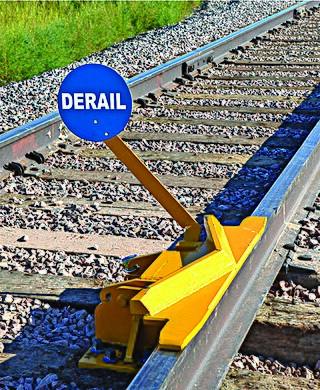

A derail or derailer is a device used to prevent fouling of a rail track by unauthorized movements of trains or unattended rolling stock. The device works by derailing the equipment as it rolls over or through it.

There have been a number of train accidents on the railway network of Victoria, Australia. Some of these are listed below.

The railways of New South Wales, Australia have had many incidents and accidents since their formation in 1831. There are close to 1000 names associated with rail-related deaths in NSW on the walls of the Australian Railway Monument in Werris Creek. Those killed were all employees of various NSW railways. The details below include deaths of employees and the general public.

The Getå railroad disaster was a train disaster caused by a landslide in Getå, a town that is now part of the municipality of Norrköping, on 1 October 1918. To date, it is the worst rail accident in Swedish history.

The Falls of Cruachan derailment occurred on 6 June 2010 on the West Highland Line in Scotland, when a passenger train travelling between Glasgow and Oban hit boulders on the line and derailed near Falls of Cruachan railway station, after a landslide. There was a small fire and one carriage was left in a precarious position on the 50-foot-high (15-metre) embankment. Sixty passengers were evacuated, some with minor injuries; eight of those were hospitalised as a precaution. However, no people were killed. In addition to blocking the line, the incident also caused the closure of the A85 road below the rail line. Both road and rail were closed for a week.

The 1990 Back Bay, Massachusetts train collision was a collision between an Amtrak passenger train, the Night Owl, and a Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) Stoughton Line commuter train just outside Back Bay station in Boston, Massachusetts, United States. An investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) found that the Amtrak train entered a speed-restricted curve at excessive speed, causing the train to derail and crash into the MBTA commuter train on an adjacent track. Although no one was killed in the accident, 453 people were injured and Back Bay station was closed for six days. Total damage was estimated at $14 million. The accident led to new speed restrictions and safety improvements in the vicinity of Back Bay and a revamp of Amtrak's locomotive engineer training program.

The Çorlu train derailment was a fatal railway accident which occurred in 2018 at the Çorlu district of Tekirdağ Province in northwestern Turkey when a train derailed, killing 24 passengers and injuring 318, including 42 severely.

The Metishto River is a tributary of the Grass River which is, in turn, a tributary of the Nelson River that ultimately flows into Hudson Bay. Its headwaters lie "a short distance from the northwest arm of Moose Lake".