Related Research Articles

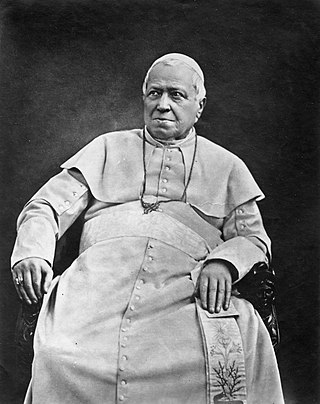

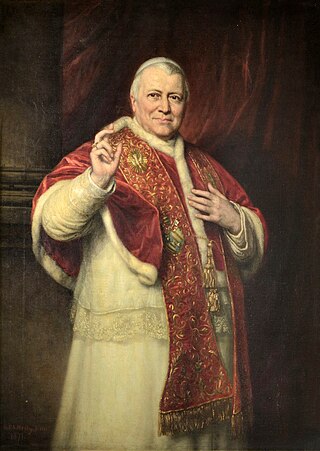

Pope Pius IX was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878, the longest verified papal reign. He was notable for convoking the First Vatican Council in 1868 and for permanently losing control of the Papal States in 1870 to the Kingdom of Italy. Thereafter, he refused to leave Vatican City, declaring himself a "prisoner of the Vatican".

The Papal States, officially the State of the Church, were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 until 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th century until the unification of Italy, between 1859 and 1870.

The unification of Italy, also known as the Risorgimento, was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single state in 1861, the Kingdom of Italy. Inspired by the rebellions in the 1820s and 1830s against the outcome of the Congress of Vienna, the unification process was precipitated by the Revolutions of 1848, and reached completion in 1871 after the Capture of Rome and its designation as the capital of the Kingdom of Italy.

Victor Emmanuel II was King of Sardinia from 23 March 1849 until 17 March 1861, when he assumed the title of King of Italy and became the first king of an independent, united Italy since the 6th century, a title he held until his death in 1878. Borrowing from the old Latin title Pater Patriae of the Roman emperors, the Italians gave him the epithet of Father of the Fatherland.

The Holy See exercised political and secular influence, as distinguished from its spiritual and pastoral activity, while the pope ruled the Papal States in central Italy.

The 1848 Revolutions in the Italian states, part of the wider Revolutions of 1848 in Europe, were organized revolts in the states of the Italian peninsula and Sicily, led by intellectuals and agitators who desired a liberal government. As Italian nationalists they sought to eliminate reactionary Austrian control. During this time, Italy was not a unified country, and was divided into many states, which, in Northern Italy, were ruled directly or indirectly by the Austrian Empire. A desire to be independent from foreign rule, and the conservative leadership of the Austrians, led Italian revolutionaries to stage revolution in order to drive out the Austrians. The revolution was led by the state of the Kingdom of Sardinia. Some uprisings in the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia, particularly in Milan, forced the Austrian General Radetzky to retreat to the Quadrilateral fortresses.

The Roman Republic was a short-lived state declared on 9 February 1849, when the government of the Papal States was temporarily replaced by a republican government due to Pope Pius IX's departure to Gaeta. The republic was led by Carlo Armellini, Giuseppe Mazzini, and Aurelio Saffi. Together they formed a triumvirate, a reflection of a form of government during the first century BC crisis of the Roman Republic.

A prisoner in the Vatican or prisoner of the Vatican described the situation of the pope with respect to Italy during the period from the capture of Rome by the armed forces of the Kingdom of Italy on 20 September 1870 until the Lateran Treaty of 11 February 1929. Part of the process of Italian unification, the city's capture ended the millennium-old temporal rule of the popes over central Italy and allowed Rome to be designated the capital of the new nation. Although the Italians did not occupy the territories of Vatican Hill delimited by the Leonine walls and offered the creation of a city-state in the area, the popes from Pius IX to Pius XI refused the proposal and described themselves as prisoners of the new Italian state.

The September Convention was a treaty, signed on 15 September 1864, between the Kingdom of Italy and the French Empire, under which:

The Roman question was a dispute regarding the temporal power of the popes as rulers of a civil territory in the context of the Italian Risorgimento. It ended with the Lateran Pacts between King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy and Pope Pius XI in 1929.

This is a timeline of the unification of Italy.

The capture of Rome on 20 September 1870 was the final event of the unification of Italy (Risorgimento), marking both the final defeat of the Papal States under Pope Pius IX and the unification of the Italian Peninsula under the Kingdom of Italy.

The Battle of Mentana was fought on November 3, 1867, near the village of Mentana, located north-east of Rome, between French-Papal troops and the Italian volunteers led by Giuseppe Garibaldi, who were attempting to capture Rome, then the main centre of the peninsula still outside of the newly unified Kingdom of Italy. The battle ended in a victory by the French-Papal troops.

Vatican during the Savoyard era describes the relation of the Vatican to Italy, after 1870, which marked the end of the Papal States, and 1929, when the papacy regained autonomy in the Lateran Treaty, a period dominated by the Roman Question.

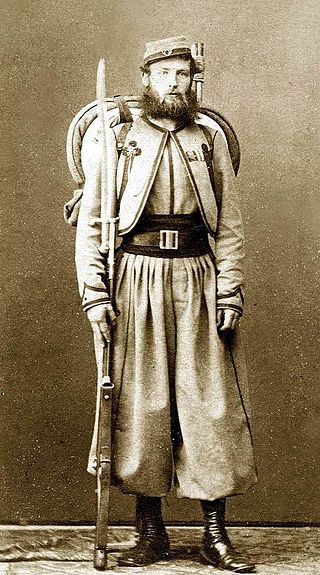

The Papal Zouaves were an infantry battalion, later regiment, dedicated to defending the Papal States. Named after the French zouave regiments, the Zuavi Pontifici were mainly young men, unmarried and Catholic, who volunteered to assist Pope Pius IX in his struggle against the Italian unificationist Risorgimento.

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi was an Italian general, patriot, revolutionary and republican. He contributed to Italian unification and the creation of the Kingdom of Italy. He is considered one of the greatest generals of modern times and one of Italy's "fathers of the fatherland", along with Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, Victor Emmanuel II of Italy and Giuseppe Mazzini. Garibaldi is also known as the "Hero of the Two Worlds" because of his military enterprises in South America and Europe.

In 1867, the French pacifist Charles Lemonnier (1806–1891) convened the Congress of Peace in Geneva, known as the International League of Peace and Liberty. It was ultimately at this conference that it was decided to abolish the sovereignty and international relations of the Holy See, something which Pius IX blamed on secret societies.

Foreign relations between Pope Pius IX and Italy were characterized by an extensive political and diplomatic conflict over Italian unification and the subsequent status of Rome after the victory of the liberal revolutionaries.

The Papal States under Pope Pius IX assumed a much more modern and secular character than had been seen under previous pontificates, and yet this progressive modernization was not nearly sufficient in resisting the tide of political liberalization and unification in Italy during the middle of the 19th century.

The modern history of the papacy is shaped by the two largest dispossessions of papal property in its history, stemming from the French Revolution and its spread to Europe, including Italy.