The United States Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) was an agency of the U.S. Department of Labor from 1933 to 1940 and the U.S. Department of Justice from 1940 to 2003.

A green card, known officially as a permanent resident card, is an identity document which shows that a person has permanent residency in the United States. Green card holders are formally known as lawful permanent residents (LPRs). As of 2023, there are an estimated 12.7 million green card holders, of whom 9 million are eligible to become United States citizens. Approximately 18,700 of them serve in the U.S. Armed Forces.

The H-1B is a visa in the United States under the Immigration and Nationality Act, section 101(a)(15)(H), that allows U.S. employers to employ foreign workers in specialty occupations. It is the largest visa category in the United States in terms of guest worker numbers. A specialty occupation requires the application of specialized knowledge and a bachelor's degree or the equivalent of work experience. The duration of stay is three years, extendable to six years, after which the visa holder can reapply. Laws limit the number of H-1B visas that are issued each year. There exist congressionally mandated caps limiting the number of H-1B visas that can be issued each fiscal year, which is 65,000 visas, and an additional 20,000 set aside for those graduating with master’s degrees or higher from a U.S. college or university. An employer must sponsor individuals for the visa. USCIS estimates there are 583,420 foreign nationals on H-1B visas as of September 30, 2019. The number of issued H-1B visas have quadrupled since the first year these visas were issued in 1991. There were 206,002 initial and continuing H-1B visas issued in 2022.

The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, enacted as division C of the Omnibus Consolidated Appropriations Act of 1997, made major changes to the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). IIRAIRA's changes became effective on April 1, 1997.

An Application for Waiver of Grounds of Inadmissibility is an application for legal entry to the United States made by an individual who is otherwise inadmissible on one or more grounds. The application is submitted to the consular office, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services office or immigration court considering the immigrant visa or adjustment of status application.

A K-1 visa is a visa issued to the fiancé or fiancée of a United States citizen to enter the United States. A K-1 visa requires a foreigner to marry his or her U.S. citizen petitioner within 90 days of entry, or depart the United States. Once the couple marries, the foreign citizen can adjust status to become a lawful permanent resident of the United States. Although a K-1 visa is legally classified as a non-immigrant visa, it usually leads to important immigration benefits and is therefore often processed by the Immigrant Visa section of United States embassies and consulates worldwide.

Parole, in the immigration laws of the United States, generally refers to official permission to enter and remain temporarily in the United States, under the supervision of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), without formal admission, and while remaining an applicant for admission.

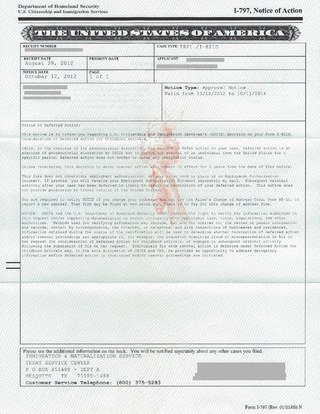

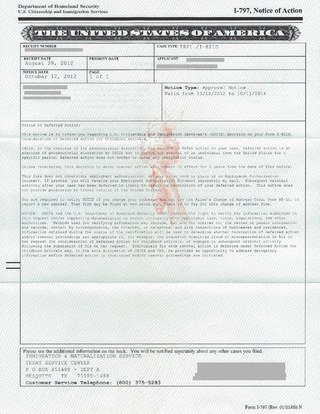

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is an agency of the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) that administers the country's naturalization and immigration system. It is a successor to the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), which was dissolved by the Homeland Security Act of 2002 and replaced by three components within the DHS: USCIS, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and Customs and Border Protection (CBP).

Illegal immigration, or unauthorized immigration, occurs when foreign nationals, known as aliens, violate US immigration laws by entering the United States unlawfully, or by lawfully entering but then remaining after the expiration of their visas, parole or temporary protected status.

Permanent Residence Under Color of Law (PRUCOL) is an immigration-related status used under some US federal and state laws for determining eligibility for some public benefits, an example being unemployment benefits. It allows for a broader group of non-citizens to qualify for benefits than just those with green cards. This status is used solely for benefit application purposes and is not recognized as an immigration status by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). This category was created by the courts and is a public benefits eligibility category. For a person to be residing "under color of law," the USCIS must know of the person’s presence in the U.S., and must provide the person with written assurance that enforcement of deportation is not planned. A person residing under PRUCOL status cannot directly apply for U.S. citizenship or sponsor family members to obtain U.S. Citizenship. A person from any country, who resides in the United States without current legal immigration status including, but not limited to, citizenship, permanent residency, unexpired immigrant visa, is an undocumented person. They are ineligible for most federal public benefits.

Adjustment of status in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) of the United States refers to the legal process of conferring permanent residency upon any alien who is a refugee, asylee, nonpermanent resident, conditional entrant, parolee, and others physically present in the United States.

Temporary protected status (TPS) is given by the United States government to eligible nationals of designated countries, as determined by the Secretary of Homeland Security, who are present in the United States. In general, the Secretary of Homeland Security may grant temporary protected status to people already present in the United States who are nationals of a country experiencing ongoing armed conflict, an environmental disaster, or any temporary or extraordinary conditions that would prevent the foreign national from returning safely and assimilating into their duty. Temporary protected status allows beneficiaries to live and, in some cases, work in the United States for a limited amount of time. As of March 2022, there are more than 400,000 foreign nationals in Temporary Protected Status.

The Immigration Act of 1903, also called the Anarchist Exclusion Act, was a law of the United States regulating immigration. It codified previous immigration law, and added four inadmissible classes: anarchists, people with epilepsy, beggars, and importers of prostitutes. It had minimal impact and its provisions related to anarchists were expanded in the Immigration Act of 1918.

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) is a United States immigration policy. It allows some individuals who, on June 15, 2012, were physically present in the United States with no lawful immigration status after having entered the country as children at least five years earlier, to receive a renewable two-year period of deferred action from deportation and to be eligible for an employment authorization document.

The U visa is a United States nonimmigrant visa which is set aside for victims of crimes who have suffered substantial mental or physical abuse while in the U.S. and who are willing to assist law enforcement and government officials in the investigation or prosecution of the criminal activity. It permits such victims to enter or remain in the US when they might not otherwise be able to do so. An advantage that comes along with the acceptance of a U-visa is the individual will have deportation protection which is important when they are collaborating with law enforcement.

The Legal Immigration Family Equity Act of 2000, also known as the LIFE Act and as the Legal Immigration and Family Equity Act, along with its Amendments, made some changes to laws surrounding immigration for family members of United States citizens and Lawful Permanent Residents, as well as people eligible for employment-based immigrant visas, in the direction of making it easier for family members and immigrant workers to move to and adjust status within the United States. It was passed on December 21, 2000, as title XI of Pub. L. 106–553 (text)(PDF).

Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (SIJS) is a special way for minors currently in the United States to adjust status to that of Lawful Permanent Resident despite unauthorized entry or unlawful presence in the United States, that might usually make them inadmissible to the United States and create bars to Adjustment of Status. The key criterion for SIJS is abuse, neglect, or abandonment by one or both parents.

Systematic Alien Verification for Entitlements (SAVE) is a program managed by United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), a branch of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). SAVE facilitates lookups on the immigration and nationality status of individuals in the United States. It is an intergovernmental initiative designed to help federal, state, tribal, and local government agencies, or by a contractor acting on the agency's behalf, to determine eligibility for benefits, licenses or grants, government credentials, or to conduct background investigations. It is one of two programs that uses the Verification Information System (VIS). The other program is the Electronic Employment Eligibility Verification Program, also known as E-Verify, and is used by employers to verify the immigration status of employees. For additional verification, SAVE relies on the Person Centric Query System (PCQS).

Immigration policy, including illegal immigration to the United States, was a signature issue of former U.S. president Donald Trump's presidential campaign, and his proposed reforms and remarks about this issue generated much publicity. Trump has repeatedly said that illegal immigrants are criminals.

The U.S. Citizenship Act of 2021 was a legislative bill that was proposed by President Joe Biden on his first day in office. It was formally introduced in the House by Representative Linda Sánchez. It died with the ending of the 117th Congress.