The Weather Underground was a far-left Marxist militant organization first active in 1969, founded on the Ann Arbor campus of the University of Michigan. Originally known as the Weathermen, the group was organized as a faction of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) national leadership. Officially known as the Weather Underground Organization (WUO) beginning in 1970, the group's express political goal was to create a revolutionary party to overthrow the United States government, which WUO believed to be imperialist.

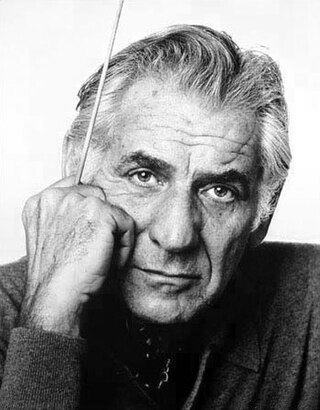

Leonard Bernstein was an American conductor, composer, pianist, music educator, author, and humanitarian. Considered to be one of the most important conductors of his time, he was the first American-born conductor to receive international acclaim. Bernstein was "one of the most prodigiously talented and successful musicians in American history" according to music critic Donal Henahan. Bernstein's honors and accolades include seven Emmy Awards, two Tony Awards, and 16 Grammy Awards as well as an Academy Award nomination. He received the Kennedy Center Honor in 1981.

Huey Percy Newton was an African American revolutionary and political activist who founded the Black Panther Party. He ran the party as its first leader and crafted its ten-point manifesto with Bobby Seale in 1966.

Thomas Kennerly Wolfe Jr. was an American author and journalist widely known for his association with New Journalism, a style of news writing and journalism developed in the 1960s and 1970s that incorporated literary techniques. Much of Wolfe's work is satirical and centres on the counterculture of the 1960s and issues related to class, social status, and the lifestyles of the economic and intellectual elites of New York City.

New York is an American biweekly magazine concerned with life, culture, politics, and style generally, with a particular emphasis on New York City.

Alberto Díaz Gutiérrez, better known as Alberto Korda or simply Korda, was a Cuban photographer, remembered for his famous image Guerrillero Heroico of Argentine Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara.

The black power movement or black liberation movement emerged in mid-1960s from the civil rights movement in the United States, reacting against its moderate, mainstream, and incremental tendencies and representing the demand for more immediate action to counter American white supremacy. Many of its ideas were influenced by Malcolm X's criticism of Martin Luther King Jr.'s peaceful protest methods. The 1965 assassination of Malcolm X, coupled with the urban riots of 1964 and 1965, ignited the movement. While thinkers such as Robert F. Williams and Malcolm X influenced the early movement, the Black Panther Party's views are widely seen as the cornerstone. They were influenced by philosophies such as pan-Africanism, black nationalism, and socialism, as well as contemporary events including the Cuban Revolution and the decolonization of Africa.

Appearances of Argentine Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara (1928–1967) in popular culture are common throughout the world. Although during his lifetime he was a highly politicized and controversial figure, in death his stylized image has been transformed into a worldwide emblem for an array of causes, representing a complex mesh of sometimes conflicting narratives. Che Guevara's image is viewed as everything from an inspirational icon of revolution, to a retro and vintage logo. Most commonly he is represented by a facial caricature originally by Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick and based on Alberto Korda's famous 1960 photograph titled Guerrillero Heroico. The evocative simulacra abbreviation of the photographic portrait allowed for easy reproduction and instant recognizability across various uses. For many around the world, Che has become a generic symbol of the underdog, the idealist, the iconoclast, or the martyr. He has become, as author Michael Casey notes in Che's Afterlife: The Legacy of an Image, "the quintessential postmodern icon signifying anything to anyone and everything to everyone."

The Panther 21 is a group of twenty-one Black Panther members who were arrested and accused of planned coordinated bombing and long-range rifle attacks on two police stations and an education office in New York City in 1969, who were all acquitted by a jury in May 1971, after revelations during the trial that police infiltrators played key organizing roles.

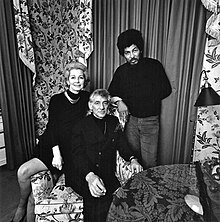

Felicia Montealegre Bernstein was an American actress born in Costa Rica.

Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers is a 1970 book by Tom Wolfe. The book, Wolfe's fourth, is composed of two essays: "These Radical Chic Evenings", first published in June 1970 in New York magazine, about a gathering Leonard Bernstein held for the Black Panther Party, and "Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers", about the response of many minorities to San Francisco's poverty programs. Both essays looked at the conflict between black rage and white guilt.

Mauve Gloves & Madmen, Clutter & Vine is a 1976 book by Tom Wolfe, consisting of eleven essays and one short story that Wolfe wrote between 1967 and 1976. It includes the essay in which he coined the term "the 'Me' Decade" to refer to the 1970s. In addition to the stories, Wolfe also illustrated the book.

Ernesto "Che" Guevara was an Argentine Marxist revolutionary, physician, author, guerrilla leader, diplomat, and military theorist. A major figure of the Cuban Revolution, his stylized visage has become a ubiquitous countercultural symbol of rebellion and global insignia in popular culture.

John Gregory Jacobs was an American student and anti-war activist in the 1960s and early 1970s. He was a leader in both Students for a Democratic Society and the Weatherman group, and an advocate of the use of violent force to overthrow the government of the United States. A fugitive after 1970, he died in 1997 in Canada.

The Black Panther Party was a Marxist–Leninist and black power political organization founded by college students Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton in October 1966 in Oakland, California. The party was active in the United States between 1966 and 1982, with chapters in many major American cities, including San Francisco, New York City, Chicago, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Philadelphia. They were also active in many prisons and had international chapters in the United Kingdom and Algeria. Upon its inception, the party's core practice was its open carry patrols ("copwatching") designed to challenge the excessive force and misconduct of the Oakland Police Department. From 1969 onward, the party created social programs, including the Free Breakfast for Children Programs, education programs, and community health clinics. The Black Panther Party advocated for class struggle, claiming to represent the proletarian vanguard.

The Che Guevara trend, or "Che chic", is a fashion trend featuring the Argentine-born revolutionary Ernesto "Che" Guevara. The phenomenon has attracted attention from the media, political commentators, songwriters, and Cuban American activists due to the popularity of the T-shirt design, Che's political beliefs, and the "irony" of buying a T-shirt depicting a Marxist icon. As op-ed commentator Chris Berg noted in The Age, "Ironically, Che Guevara's longevity as a cultural symbol has been thanks to the very economic system he sought to destroy".

Donald Lee Cox, known as Field Marshal DC, was an early member of the leadership of the African American revolutionary leftist organization the Black Panther Party, joining the group in 1967. Cox was titled the Field Marshal of the group during the years he actively participated in its leadership, due to his familiarity with and writing about guns.

Nostalgie de la boue is a French phrase meaning the attraction to low-life culture, experience, and degradation, found at times both in individuals and in cultural movements.

Communist chic are elements of popular culture such as fashion and commodities based on communist symbols and other things associated with Marxism, Leninism, socialism and communism. Typical examples are T-shirts and other memorabilia with Alberto Korda's iconic photo of Che Guevara.