A turban is a type of headwear based on cloth winding. Featuring many variations, it is worn as customary headwear by people of various cultures. Communities with prominent turban-wearing traditions can be found in the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, the Balkans, the Caucasus, Central Asia, North Africa, West Africa, East Africa, and amongst some Turkic peoples in Russia.

The fez, also called tarboosh/tarboush, is a felt headdress in the shape of a short, cylindrical, peakless hat, usually red, typically with a black tassel attached to the top. The name "fez" refers to the Moroccan city of Fez, where the dye to color the hat was extracted from crimson berries.

A scarf is a long piece of fabric that is worn on or around the neck, shoulders, or head. A scarf is used for warmth, sun protection, cleanliness, fashion, religious reasons, or to show support for a sports club or team. Scarves can be made from materials including wool, linen, silk, and cotton. It is a common type of neckwear and a perennial accessory.

Folk costume, traditional dress, traditional attire or folk attire, is clothing associated with a particular ethnic group, nation or region, and is an expression of cultural, religious or national identity. If the clothing is that of an ethnic group, it may also be called ethnic clothing or ethnic dress. Traditional clothing often has two forms: everyday wear, and formal wear. The word "costume" in this context is sometimes considered pejorative, as the word has more than one meaning, and thus "clothing", "dress", "attire" or "regalia" can be substituted without offense.

A krama is a sturdy traditional Cambodian garment with many uses, including as a scarf, bandanna, to cover the face, for decorative purposes, and as a hammock for children. It may also be used as a garrote by Bokator fighters, who also wrap the krama around their waists, heads and fists. It is worn by men, women and children, and can be fairly ornate, though most typical kramas contain a gingham pattern of some sort, and traditionally come in either red or blue. It is the Cambodian national symbol.

A headscarf is a scarf covering most or all of the top of a person's, usually women's, hair and head, leaving the face uncovered. A headscarf is formed of a triangular cloth or a square cloth folded into a triangle, with which the head is covered.

Kurdish traditional clothing, also known as Kurdish dress, refers to the folk costumes of the Kurdish people. The traditions typically vary across different regions and tribes of Kurdistan, but it has some common elements. Historically, Kurdish clothing was more complex and varied, but it has evolved to a simpler form over time. It is also prominently worn during festivals and special occasions such as Newroz.

The Hejazi turban, also spelled Hijazi turban, is a type of the turban headdress native to the region of Hejaz in modern-day western Saudi Arabia.

Check is a pattern of modified stripes consisting of crossed horizontal and vertical lines which form squares. The pattern typically contains two colours where a single checker is surrounded on all four sides by a checker of a different colour.

Palestinian traditional clothing are the types of clothing historically and sometimes still presently worn by Palestinians. Foreign travelers to Palestine in the 19th and early 20th centuries often commented on the rich variety of the costumes worn, particularly by the fellaheen or village women. Many of the handcrafted garments were richly embroidered and the creation and maintenance of these items played a significant role in the lives of the region's women.

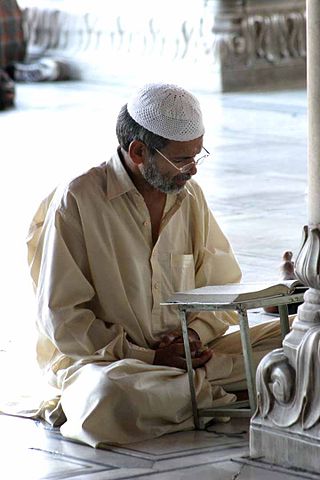

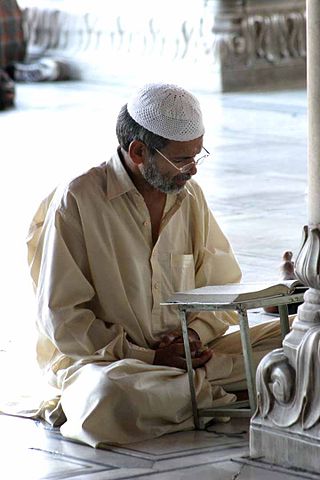

The Taqiyah, also known as tagiyah or araqchin, is a short, rounded skullcap worn by Muslim men. In the United States and the United Kingdom, it is also referred to as a "kufi", although the Kufi typically has more of an African connotation. Aside from being an adornment, the taqiyah has deeply ingrained significance in Islamic culture, reflecting the wearer's faith, devotion, and sometimes regional identity. While the taqiyah is deeply rooted in Muslim traditions, its use varies based on cultural context rather than strict religious guidelines.

Jewish religious clothing is apparel worn by Jews in connection with the practice of the Jewish religion. Jewish religious clothing has changed over time while maintaining the influences of biblical commandments and Jewish religious law regarding clothing and modesty (tzniut). Contemporary styles in the wider culture also have a bearing on Jewish religious clothing, although this extent is limited.

Headgear, headwear, or headdress is any element of clothing which is worn on one's head, including hats, helmets, turbans and many other types. Headgear is worn for many purposes, including protection against the elements, decoration, or for religious or cultural reasons, including social conventions.

The clothing of the people in biblical times was made from wool, linen, animal skins, and perhaps silk. Most events in the Hebrew Bible and New Testament take place in ancient Israel, and thus most biblical clothing is ancient Hebrew clothing. They wore underwear and cloth skirts.

The sudra is a rectangular piece of cloth that has been worn as a headdress, scarf, or neckerchief in ancient Jewish tradition. Over time, it held many different functions and is today sometimes understood to be of great cultural and/or religious significance to Jews.

A draped turban or turban hat is a millinery design in which fabric is draped to create headwear closely moulded to the head. Sometimes it may be stiffened or padded, although simpler versions may just comprise wound fabric that is knotted or stitched. It may include a peak, feather or other details to add height. It generally covers most or all of the hair.

An agal is a clothing accessory traditionally worn by Arab men. It is a doubled black cord used to keep a keffiyeh in place on the wearer's head. Agals are traditionally made of goat or camel hair. Modern agals typically use cord manufactured for this purpose, but plain rope is still occasionally utilized.

The Palestinian keffiyeh is a distinctly patterned black-and-white keffiyeh.

Fashion activism is the practice of using fashion as a medium for social, political, and environmental change. The term has been used recurringly in the works of designers and scholars Lynda Grose, Kate Fletcher, Mathilda Tham, Kirsi Niinimäki, Anja-Lisa Hirscher, Zoe Romano, and Orsola de Castro, as they refer to systemic social and political change through the means of fashion. It is also a term used by some fashion designers, one being Stella McCartney. The spectacle of fashion activism as street protest has also been a theme in Paris Catwalk shows. The term is used by Céline Semaan, co-founder of the Slow Factory Foundation.