Communism

The Austrian Communist Party was founded on 3 November 1918 by Ruth Fischer and Paul Friedländer, a medical student she married in 1917, who later died in a Nazi prison or concentration camp. [8] She claimed in her memoir, Stalin and German Communism, that she was listed as member number one. Eight days later, she claimed, a crowd of rioters proclaimed her editor of Vienna's largest daily, the Neue Freie Presse, and she was arrested and charged with treason, but released under amnesty. She opposed the failed attempt to seize power in Austria in June 1919 instigated by the Hungarian communist Erno Bettelheim, and during the recriminations that followed, she left her husband and moved to Berlin. She visited the Comintern representative Karl Radek many times while he was interned in Moabit prison, acting as his contact with the Communist Party of Germany. [9] In a memoir of his year in Berlin, Radek commented: "She gave the impression of being a lively, if uneducated female .. I saw that she could grasp ideas easily, but that they didn't sink in very far, and she could easily fall under some other influence." [10]

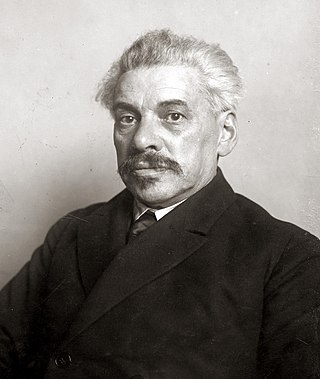

In 1921, Fischer became leader of the Berlin branch of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), and she and Arkadi Maslow emerged as leaders of the left of the communist party, who blamed the party's over-cautious leadership for the failure of the March Action in 1921, and opposed the tactic of a 'united front' with the German Social Democratic Party. [11] The German authorities tried to forcibly repatriate her to Austria. Thus she married the fellow communist Gustav Golke (1889–1937, executed in the Soviet Great Purge), in order to be naturalised as a German. [12] Heinrich Brandler was the national leader of the Communist Party of Germany. In the early months of 1923, Ruth Fischer and urged Brandler to organize an uprising on the model provided by the Bolsheviks in 1917. [13] Together they developed the "theory of the offensive". Fischer denounced the leadership for "making concessions to social democracy", for "opportunism" and for "ideological liquidationism and theoretical revisionism". Chris Harman, author of The Lost Revolution (1982) has pointed out: "Articulate and energetic, they were able to gather around them many of the new workers who had joined the party." [14] Although she appeared to represent a minority view in the Communist Party of Germany at that time, Comintern ordered that she should be co-opted onto its Central Committee in April 1923.

In 1923, Fischer appealed to a group of Nazi students, proclaiming that "Those who call for a struggle against Jewish capital are already, gentlemen, class strugglers, even if they don’t know it. You are against Jewish capital and want to fight the speculators. Very good. Throw down the Jewish capitalists, hang them from the lamp-post, stamp on them. But, gentlemen, what is your position with respect to the big capitalists, the Stinneses and Klöckners?" [15] [16]

Ruth Fischer argued that the Communist Party of Germany leaders were saying: "In no circumstances must we proclaim the general strike. The bourgeoisie will discover our plans and destroy us before we have moved. On the contrary, we must calm the masses, hold back our people in the factories and the unemployed committees until the government thinks the moment of danger has passed." [17]

When the leaders of the Communist Party of Germany met leaders in Moscow in September 1923 to discuss the prospect of seizing power that autumn, Leon Trotsky was so disturbed by the antagonism between the different factions that, out of loyalty to Brandler, he proposed that Maslow and Fischer be ordered to stay in Moscow. In the event, it was agreed that Maslow would stay, but Fischer could return to Germany. [18]

After the failure of the Hamburg Uprising, and Maslow's return to Germany, Fischer, Maslow and Ernst Thälmann gained control of the KPD, at Brandler's expense. In April 1924, the 9th party convention elected her and Maslow co-chairpersons of the Communist Party of Germany. In May 1924, she travelled to the UK as a fraternal delegate to a sixth congress of the Communist Party of Great Britain, whom she accused of being too close to the Labour Party, and narrowly avoided being arrested in Manchester. She was elected to the Reichstag under her then legal name Elfriede Golke, and to the Prussian House of Representatives. In January 1925, she was arrested in Austria, after crossing the border illegally on a mission to revive the Austrian communist party. [19]

During the power struggle in the Soviet Union following the death of Lenin, the trio backed the Comintern chairman Grigory Zinoviev, who at that time was aligned with Joseph Stalin, against Trotsky and Radek. In June 1924, she led the German delegation to the Fifth Congress of Comintern, where she denounced Trotsky in public, in language not previously heard. At the sixth congress of the KPD, in 1925, she went on to attack the two most famous martyrs of German communism, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht for having "burdened us with great errors which we must eradicate." Writing in a party journal, she likened Luxemburg's influence to a syphilis bacillus. [20]

By August 1925, Zinoviev and other soviet leaders had decided that Fischer and Maslow were unreliable, and the executive of Comintern passed a resolution attacking them by name, without mentioning Thälmann. [21] She was ordered to stay in Moscow (while Maslow was in prison in Germany), and Thälmann took over the leadership of the German party. When the rift between Zinoviev and Stalin became public, she began meeting Zinoviev to settle their past differences. In February 1926, she was summoned by Stalin, who told her she could return to Germany and be readmitted to the party leadership if she submitted to the party line, which she refused to do. [22] When the executive of Comintern held a special session, private letters she had written, which had been intercepted by the censorship were read out, including one to Maslow, in which she wrote "We are condemned to death, since terror reigns in Leningrad." [23] From then, she was publicly linked to the anti-Stalinist left, despite her previous clashes with Trotsky. On 19 August 1926, she and Maslow were expelled from the KPD.

Anti-Stalinism

In Germany, she and Maslow formed a splinter group to the left of the KPD, arguing that Stalin was the leader of a counter-revolution in the USSR, which was ruled by a new class of bureaucrats running a form of state capitalism. She lost her Reichstag seat in 1928, and fled to Paris in 1933 and in August the same year the Nazi government annulled her naturalisation of 1923. When Trotsky founded the Fourth International in 1938, he 'set great store' by the accession of Fischer, who visited him frequently in France, though her opposition to Stalinism went further than his. [24]

In 1941, Fischer left France for the United States. [1]

In 1947, she testified before HUAC against her brothers Gerhart and Hanns. Her testimony against Hanns resulted in his blacklisting and deportation. She testified that Gerhart was an important Comintern agent. [1]

During the early years of the Cold War Fischer also served as an agent for the precursor to the CIA, The Pond. Under code-named "Alice Miller," she was considered a key Pond agent for eight years,working under her cover as a correspondent, including for the North American Newspaper Alliance. Her tasks included getting intelligence on Stalinists, Marxists and socialists in Europe, Africa and China. [2]

In 1948, she published her memoir Stalin and German Communism - but the accuracy of her account of events that had happened a quarter of a century or more before she was writing has been challenged. Rosa Luxemburg's biographer, J. P. Nettl, described the book as "generally unreliable; in places deliberately so." [25] E. H. Carr looked into one of the claims made in the book and concluded that it was "inaccurate in every particular that can be checked." [26]

Isaac Deutscher, a biographer of Trotsky and Stalin, described her as a "young, trumpet-tongued woman, without any revolutionary experience or merit, yet idolized by the Communists of Berlin." [27]

In 1955, Fischer returned to Paris and published her books Stalin and German Communism and Die Umformung der Sowjetgesellschaft.