The Supermarine Attacker is a British single-seat naval jet fighter designed and produced by aircraft manufacturer Supermarine for the Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm (FAA). It was the first jet fighter to enter operational service with the FAA.

The Handley Page HP.88 was a British research aircraft, built in the early 1950s for Handley Page to test the aerodynamics of the Victor crescent wing design, and was intended to be a scaled-down version of that aircraft.

The Bréguet Br 960 Vultur was a prototype two-seat carrier-based attack and anti-submarine aircraft (ASW) built for the French Navy during the early 1950s. Meeting contradictory endurance and speed requirements, it was designed as a "mixed-power" aircraft with a turboprop engine in the front and a turbojet in the rear. Only two examples were built, but the second aircraft was rebuilt as the prototype of the Bréguet 1050 Alizé ASW aircraft after the Navy dropped the idea of a turboprop attack aircraft in the mid-1950s.

The Nord 1500 Griffon is an experimental ramjet-powered interceptor aircraft designed and built by French state-owned aircraft manufacturer Nord Aviation. The Griffon was developed to become a Mach 2 follow on to the supersonic Nord Gerfaut research aircraft. Development of the aircraft began in earnest after the receipt of a letter of intent in 1953 for a pair of unarmed research aircraft. The design featured an innovative dual propulsion turbojet-ramjet configuration; the former being used to takeoff and attain sufficient speed to start the latter.

The SNECMA C.450 Coléoptère was a tail-sitting vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) aircraft designed by the French company SNECMA and manufactured by Nord Aviation. While work on the aircraft proceeded to the test flying phase, the project never progressed beyond experimental purposes.

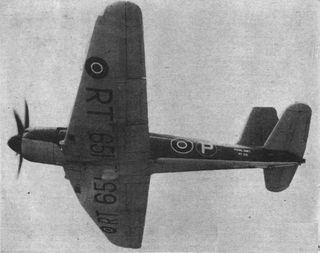

The Blackburn B.48 Firecrest, given the SBAC designation YA.1, was a single-engine naval strike fighter built by Blackburn Aircraft for service with the British Fleet Air Arm during the Second World War. It was a development of the troubled Firebrand, designed to Air Ministry Specification S.28/43, for an improved aircraft more suited to carrier operations. Three prototypes were ordered with the company designation of B-48 and the informal name of "Firecrest", but only two of them actually flew. The development of the aircraft was prolonged by significant design changes and slow deliveries of components, but the determination by the Ministry of Supply in 1946 that the airframe did not meet the requirements for a strike fighter doomed the aircraft. Construction of two of the prototypes was continued to gain flight-test data and the third was allocated to strength testing. The two flying aircraft were sold back to Blackburn in 1950 for disposal and the other aircraft survived until 1952.

The Arsenal VG 70 was a single-seat monoplane research aircraft flown in France shortly after World War II to assist in the development of high-speed jet fighters. Lacking an indigenous turbojet engine, the aircraft was fitted with a German Junkers Jumo 004. Unlike most jet-powered aircraft of the period, the swept wing was wooden as was the tail structure. The under-powered VG 70 made its maiden flight in 1948, but only flew five times before the program was terminated the following year.

The Arsenal VG 90 was a French carrier-based jet-engined interceptor developed in the late 1940s. It was intended to compete for an Aéronavale contract and first flew in 1949. It set a speed record for a French aircraft the following year, but both of the completed prototypes were destroyed in fatal crashes and the program was cancelled in 1952 before the third prototype was finished. The Aéronavale contract was eventually awarded to a license-built British aircraft. The remains of the last VG 90 were scrapped in 1978.

The Sud-Ouest SO.6000 Triton is an early experimental French jet aircraft. It has the distinction of being the first indigenously-designed jet-powered aircraft to be flown by the nation, having been designed and manufactured during the 1940s by the French aircraft construction consortium SNCASO.

The Nord Gerfaut (Gyrfalcon) was a French delta-wing experimental research aircraft. It was the first European aircraft to exceed Mach 1 in level flight without the use of an afterburner. A pair of aircraft were built for the primary purpose of investigating the transonic regime. The Gerfaut I conducted its maiden flight in 1954; it was followed by the improved Gerfaut II two years later. Both aircraft were flown for several years for experimental purposes, being significantly upgraded over time. During the course of these test flights, the second prototype establishment multiple time-to-altitude world records. In the late 1950s, the type was used to flight-test various aerial missiles. Both aircraft performed their final flights in 1959; they were subsequently used as targets at the Military Test Range at Cazaux.

The Leduc 022 was the prototype of a mixed-power French interceptor built in the mid-1950s. Designer René Leduc had been developing ramjet-powered aircraft since before World War II and had flown a series of experimental aircraft, the Leduc 0.10 and Leduc 0.21, throughout the 1950s before he was awarded a contract for two examples of a short-range supersonic interceptor armed with two air-to-air missiles (AAMs).

The Nord 2200 was a French carrier-based, jet-engined interceptor developed in the late 1940s. It was intended to compete for an Aéronavale contract, but was not selected for production after a 1950 accident badly damaged the sole prototype. It was repaired and resumed flight testing the following year, which including evaluating rocket-assisted take offs. After the aircraft made its last flight in 1954, it was used as a gunnery target. Much of the airframe was recovered in the 1980s, but its current disposition is uncertain.

The SNCASO SO.9000 Trident is a French jet and rocket powered interceptor aircraft built by aircraft manufacturer SNCASO during the 1950s. As part of a wider effort to re-build French military power during the late 1940s and to furnish France with advanced, new domestically produced designs, a request for a supersonic-capable point-defence interceptor aircraft to equip the French Air Force was issued to SNCASO. In response, the firm designed the mixed-propulsion Trident, powered by a single SEPR rocket engine, which was augmented by wingtip-mounted turbojet engines, and the Air Force ordered two prototypes.

The SNCASE Grognard was designed as a single-seat, low-level ground-attack aircraft. Although in development in the 1950s for the French Armée de l'Air, the program was cancelled in favor of the Sud-Ouest Vautour II.

The SNCASO SO.4000 was an experimental French twin-engine bomber of the 1950s. It was the first French jet bomber developed, but it never entered operational service.

The SNCAC NC-600 was a prototype French twin-engined long-range fighter aircraft, developed by SNCAC from the earlier Hanriot H.220 fighter. The type never entered service, with development being ended by the French surrender in June 1940.

The SNCASO SO.8000 Narval was a French carrier-based strike fighter designed by Sud-Ouest in the late 1940s. The French Navy ordered two prototypes in 1946 and they made their maiden flights three years later. They were plagued by aerodynamic problems and unreliability issues with their piston engines. The aircraft proved to be slow, lacking in lateral and longitudinal stability and unsuitable for carrier operations; it did not enter production.

The Sud-Ouest SO.6020 Espadon (Swordfish) was a French post-war prototype interceptor designed and built by SNCASO during the late 1940s. The French Air Force judged the design a failure despite some records being set and cancelled plans to put it into service in 1951. Only four aircraft were built and they were later modified to serve as testbeds for the mixed rocket and turbojet-powered SNCASO SO.9000 Trident program. Only one badly damaged aircraft survives.

The SNCAC NC.1070 was a piston engined attack and torpedo bomber designed and built in France shortly after World War II. The second prototype, the NC1071, was the first French multi-jet turbine powered aircraft.

The SNCAC NC.271 was a French experimental aircraft built by SNCAC in the late 1940s, as a 1:2.5 scale model of the proposed SNCAC NC.270 jet bomber, featuring swept-back wings, using SNCASE SE-161 Languedoc N0.31 F-BCUT as a launch platform.