The Gūr-i Amīr or Guri Amir is a mausoleum of the Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. It occupies an important place in the history of Central Asian architecture as the precursor for and had influence on later Mughal architecture tombs, including Gardens of Babur in Kabul, Humayun's Tomb in Delhi and the Taj Mahal in Agra, built by Timur's Indian descendants, Turco-Mongols that followed Indian culture with Central Asian influences. Mughals established the ruling Mughal dynasty of the Indian subcontinent. The mausoleum has been heavily restored over the course of its existence.

Humayun's tomb is the tomb of Mughal emperor, Mirza Nasir al-Din Muhammad commonly known as Humayun situated in Delhi, India. The tomb was commissioned by Humayun's first wife and chief consort, Empress Bega Begum under her patronage in 1558, and designed by Mirak Mirza Ghiyas and his son, Sayyid Muhammad, Persian architects chosen by her. It was the first garden-tomb on the Indian subcontinent, and is located in Nizamuddin East, Delhi, close to the Dina-panah Citadel, also known as Purana Qila, that Humayun found in 1538. It was also the first structure to use red sandstone at such a scale. The tomb was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993, and since then has undergone extensive restoration work, which is complete. Besides the main tomb enclosure of Humayun, several smaller monuments dot the pathway leading up to it, from the main entrance in the West, including one that even pre-dates the main tomb itself, by twenty years; it is the tomb complex of Isa Khan Niazi, an Afghan noble in Sher Shah Suri's court of the Suri dynasty, who fought against the Mughals, constructed in 1547 CE.

Mughal architecture is the type of Indo-Islamic architecture developed by the Mughals in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries throughout the ever-changing extent of their empire in the Indian subcontinent. It developed from the architectural styles of earlier Muslim dynasties in India and from Iranian and Central Asian architectural traditions, particularly Timurid architecture. It also further incorporated and syncretized influences from wider Indian architecture, especially during the reign of Akbar. Mughal buildings have a uniform pattern of structure and character, including large bulbous domes, slender minarets at the corners, massive halls, large vaulted gateways, and delicate ornamentation; examples of the style can be found in modern-day Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India and Pakistan.

The Mausoleum of Khawaja Ahmed Yasawi is a mausoleum in the city of Turkestan, in southern Kazakhstan. The structure was commissioned in 1389 by Timur, who ruled the area as part of the expansive Timurid Empire, to replace a smaller 12th-century mausoleum of the famous Turkic poet and Sufi mystic, Khoja Ahmed Yasawi (1093–1166). However, construction was halted with the death of Timur in 1405.

The Green Mosque, also known as the Mosque of Mehmed I, is a part of a larger complex on the east side of Bursa, Turkey, the former capital of the Ottoman Turks before they captured Constantinople in 1453. The complex consists of a mosque, a mausoleum known as the Green Tomb, a madrasa, a public kitchen, and a bathhouse. The name Green Mosque comes from its green and blue interior tile decorations. It is part of the historic UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Tomb of Jahangir is a 17th-century mausoleum built for the Mughal Emperor Jahangir. The mausoleum dates from 1637, and is located in Shahdara Bagh near city of Lahore, Pakistan, along the banks of the Ravi River. The site is famous for its interiors that are extensively embellished with frescoes and marble, and its exterior that is richly decorated with pietra dura. The tomb, along with the adjacent Akbari Sarai and the Tomb of Asif Khan, are part of an ensemble currently on the tentative list for UNESCO World Heritage status.

Safdarjung's tomb is a sandstone and marble mausoleum in Delhi, India. It was built in 1754 in the late Mughal Empire style for Nawab Safdarjung. The monument has an ambience of spaciousness and an imposing presence with its domed and arched red, brown and white coloured structures. Safdarjung, Nawab of Oudh, was made prime minister of the Mughal Empire when Ahmed Shah Bahadur ascended the throne in 1748.

Chini ka Rauza is a funerary monument, rauza in Agra, India, containing the tomb of Afzal Khan Shirazi, a scholar and poet who was the Grand Vizier of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan. The tomb was built in 1635. The Chini Ka Rauza is situated just 1 kilometre north of Itmad-Ud-Daulah's Tomb, on the eastern (left) bank of Yamuna river in Agra, and 2 kilometres away from the Taj Mahal.

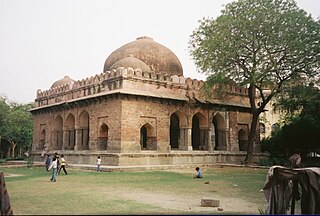

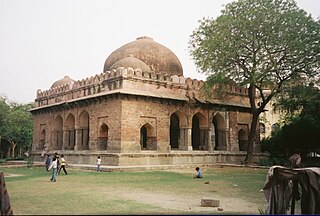

Barakhamba, also known as Barakhamba Monument, is a 14th-century tomb building from the Tughlaq period that is located in New Delhi, India. Barakhamba means '12 Pillars' in Urdu and Hindi languages. The name has also been used for an upscale modern metro road named the "Barakhamba road" in Connaught Place at the heart of the city.

Jamali Kamali Mosque and Tomb, located in the Archaeological Village complex in Mehrauli, Delhi, India, comprise two monuments adjacent to each other; one is the mosque and the other is the tomb of Jamali and Kamali. Their names are tagged together as "Jamali Kamali" for the mosque as well as the tomb since they are buried adjacent to each other. The mosque and the tomb were constructed in 1528-1529, and Jamali was buried in the tomb after his death in 1535.

Timurid architecture was an important stage in the architectural history of Iran and Central Asia during the late 14th and 15th centuries. The Timurid Empire (1370–1507), founded by Timur and conquering most of this region, oversaw a cultural renaissance. In architecture, the Timurid dynasty patronized the construction of palaces, mausoleums, and religious monuments across the region. Their architecture is distinguished by its grand scale, luxurious decoration in tilework, and sophisticated geometric vaulting. This architectural style, along with other aspects of Timurid art, spread across the empire and subsequently influenced the architecture of other empires from the Middle East to the Indian subcontinent.

Sunder Nursery, formerly called Azim Bagh or Bagh-e-Azeem, is a 16th-century heritage park complex adjacent to the Humayun's Tomb, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Delhi. Originally known as Azim Bagh and built by the Mughals in the 16th century, it lies on the Mughal-era Grand Trunk Road, and is spread over 90 acres. Future plans aim to link nearby areas to develop it into India's largest park covering 900 acres.

Tombs of Battashewala Complex is an Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) protected monument in Nizamuddin East, Delhi. The funerary complex, consists of three Mughal period tombs, known as the Bara Batashewala Mahal, the Chota Batashewala Mahal, an unidentified Mughal tomb and arched compound wall enclosures.

Persian domes or Iranian domes have an ancient origin and a history extending to the modern era. The use of domes in ancient Mesopotamia was carried forward through a succession of empires in the Greater Iran region.

The Shrine of Khwaja Abd Allah, commonly called the Shrine at Gazur Gah and the Abdullah Ansari Shrine Complex, is the funerary compound of the Sufi saint Khwaja Abdullah Ansari. It is located at the village of Gazur Gah, three kilometers northeast of Herat, Afghanistan. The Historic Cities Programme of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture has initiated repairs on the complex since 2005.

Sher Mandal is a 16th-century historic Library within the Purana Qila fort located in Delhi, India. Designed in a blend of Indo-islamic, Timurid and Persian architecture, it is the only surviving palace structure within the fort and has become a tourist attraction.

The tomb of the noble Isa Khan Niazi is located in the Humayun's Tomb complex in Delhi, India. The mausoleum, octagonal in shape and built mainly of red sandstone, was built in 1547–1548 during the reign of Sher Shah Suri. The mosque of Isa Khan is located west of the mausoleum, which along with other buildings form the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Humayun's tomb complex.

The Afsarwala tomb complex consists of a tomb and mosque, located inside the Humayun's Tomb complex in Delhi, India. The mausoleum houses the tomb of an unknown person. The tomb, together with other structures, forms the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Humayun's tomb complex.

Nila Gumbad is a tomb located within the Humayun's Tomb complex at Delhi, India. Historians are unsure about the identity of the person who has been buried. Some claim that it houses the tomb of an attendant of a Mughal noble and was buried during the reign of Jahangir. According to others, the tomb existed much before the Humayun's Tomb was constructed. At the time of construction, it was covered with glazed tiles most of which have been destroyed. This building along with other buildings form the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Humayun's Tomb complex.

Decoration in Ottoman architecture takes on several forms, the most prominent of which include tile decoration, painted decoration, and stone carving. Beginning in the 14th century, early Ottoman decoration was largely a continuation of earlier Seljuk styles in Anatolia as well as other predominant styles of decoration found in Islamic art and architecture at the time. Over the course of the next few centuries, a distinctive Ottoman repertoire of motifs evolved, mostly floral motifs, such as rumî, hatayî, and saz styles. Calligraphic inscriptions, most characteristically in a thuluth script, were also a mainstay. From the 18th century onward, this repertoire became increasingly influenced by Western European art and architecture and went as far as directly borrowing techniques and styles from the latter.