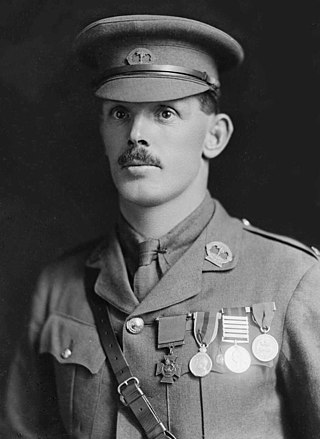

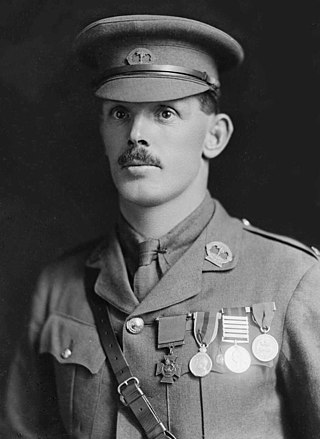

Brigadier Leslie Wilton Andrew, was a senior officer in the New Zealand Military Forces and a recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award of the British Commonwealth for gallantry "in the face of the enemy". He received the decoration for his actions during the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917.

Cyril Royston Guyton Bassett, VC was a New Zealand recipient of the Victoria Cross (VC), the highest award for gallantry "in the face of the enemy" that could be awarded to British and Empire forces at the time. He was the only soldier serving with the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) to be awarded the VC in the Gallipoli Campaign of the First World War.

Richard Charles Travis, was a New Zealand soldier who fought during the First World War and was posthumously decorated with the Victoria Cross (VC), the highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to Commonwealth forces.

William James Hardham, VC was a New Zealand soldier who was a recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry "in the face of the enemy" that could be awarded at the time to military personnel of the British Empire.

Percy Valentine Storkey, VC was a New Zealand-born Australian recipient of the Victoria Cross (VC), the highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.

Donald Forrester Brown, VC was a New Zealand recipient of the Victoria Cross (VC), the highest award for valour "in the face of the enemy" that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.

Harry Cator VC, MM was an English recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.

Thomas Cooke, VC was a New Zealand-born soldier who served in the Australian Imperial Force during the First World War. He was a recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry "in the face of the enemy" that can be awarded to personnel of British and Commonwealth forces.

William Merrifield VC, MM was an English-born Canadian recipient of the Victoria Cross (VC), the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces. A soldier with Canadian Expeditionary Force during the First World War, he was awarded the VC for his actions on 1 October 1918, during the Battle of the Canal du Nord. Earlier in the war he had been awarded the Military Medal.

Samuel Lewis Honey, was a soldier in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, and posthumous recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest military award for gallantry in the face of the enemy given to British and Commonwealth forces, during the First World War. He had already been awarded the Military Medal and Distinguished Conduct Medal for actions earlier in the war.

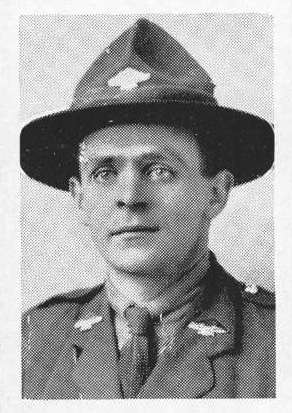

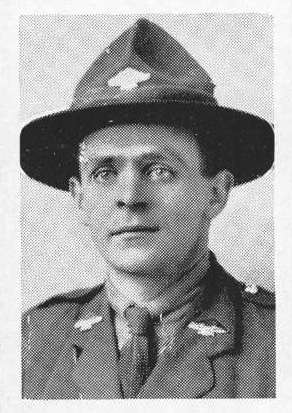

Henry James Nicholas, was a New Zealand recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award for valour "in the face of the enemy" that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.

William Ratcliffe VC MM was an English private of South Lancashire Regiment. He was a recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.

Percy Herbert Cherry, VC, MC was an Australian recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest decoration for gallantry "in the face of the enemy" that can be awarded to members of the British and Commonwealth armed forces. The award was granted posthumously for Cherry's actions during an attack on the French village of Lagnicourt which was strongly defended by German forces.

Arthur Henderson VC, MC was a Scottish recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.

James Crichton, VC was an Irish-born soldier and a recipient of the Victoria Cross (VC), the highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that could be awarded at that time to British and Commonwealth forces.

John Gildroy Grant, VC was a soldier in the New Zealand Military Forces during the First World War. He was a recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry "in the face of the enemy" that could be awarded at the time to British and Commonwealth forces.

Harry John Laurent, VC was a New Zealand recipient of the Victoria Cross (VC), the highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.

Reginald Stanley Judson, was a New Zealand recipient of the Victoria Cross (VC), the highest military award for gallantry "in the face of the enemy" given to British and Commonwealth forces. He was awarded the VC for his actions in the Second Battle of Bapaume during the First World War.

Samuel Forsyth, VC was a New Zealand recipient of the Victoria Cross (VC), the highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that could be awarded at the time to British and Commonwealth forces.

Randolph Gordon Ridling, was a New Zealand soldier who served during the First World War on the Western Front with the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. He was awarded the Albert Medal in 1919 for saving the life of a soldier during a grenade training exercise the previous year. After the war, he studied at the University of Cambridge and subsequently worked in the education sector in New Zealand. In 1971, the Albert Medal was disestablished by royal warrant as a gallantry award and living recipients were required to swap their medals for the George Cross. Ridling, for sentimental reasons, sought an exemption from Queen Elizabeth II to retain his medal, which was granted. He died in 1975, aged 86.