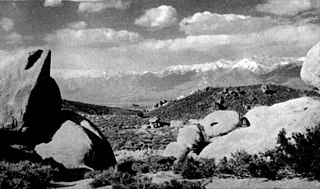

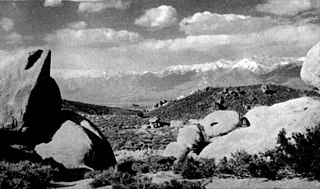

The Tehachapi Mountains are a mountain range in the Transverse Ranges system of California in the Western United States. The range extends for approximately 40 miles (64 km) in southern Kern County and northwestern Los Angeles County and form part of the boundary between the San Joaquin Valley and the Mojave Desert.

The Tejon Pass, previously known as Portezuelo de Cortes, Portezuela de Castac, and Fort Tejon Pass is a mountain pass between the southwest end of the Tehachapi Mountains and northeastern San Emigdio Mountains, linking Southern California north to the Central Valley. Both the pass and the grade north of it to the Central Valley are commonly referred to as "the Grapevine". It has been traversed by major roads such as the El Camino Viejo, the Stockton – Los Angeles Road, the Ridge Route, U.S. Route 99, and now Interstate 5.

Fort Tejon in California is a former United States Army outpost which was intermittently active from June 24, 1854, until September 11, 1864. It is located in the Grapevine Canyon between the San Emigdio Mountains and Tehachapi Mountains. It is in the area of Tejon Pass along Interstate 5 in Kern County, California, the main route through the mountain ranges separating the Central Valley from the Los Angeles Basin and Southern California. The fort's location protected the San Joaquin Valley from the south and west.

Tejon Ranch Company, based in Lebec, California, is one of the largest private landowners in California. The company was incorporated in 1936 to organize the ownership of a large tract of land that was consolidated from four Mexican land grants acquired in the 1850s and 1860s by ranch founder Edward Fitzgerald Beale.

The Kawaiisu are a Native Californian ethnic group in the United States who live in the Tehachapi Valley and to the north across the Tehachapi Pass in the southern Sierra Nevada, toward Lake Isabella and Walker Pass. Historically, the Kawaiisu also traveled eastward on food-gathering trips to areas in the northern Mojave Desert, to the north and northeast of the Antelope Valley, Searles Valley, as far east as the Panamint Valley, the Panamint Mountains, and the western edge of Death Valley. Today, some Kawaiisu people are enrolled in the Tule River Indian Tribe.

Elizabeth Lake is a natural sag pond that lies directly on the San Andreas Fault in the northern Sierra Pelona Mountains, in northwestern Los Angeles County, southern California.

Rancho El Tejón was a 97,617-acre (395.04 km2) Mexican land grant in the Tehachapi Mountains and northeastern San Emigdio Mountains, in present-day Kern County, California. It was granted in 1843 by Governor Manuel Micheltorena to José Antonio Aguirre and Ygnacio del Valle.

Rancho Castac or Rancho Castec was a 22,178-acre (89.75 km2) Mexican land grant in present-day Kern and Los Angeles counties, California, made by Governor Manuel Micheltorena to Jose Maria Covarrubias in 1843. The rancho in the Tehachapi Mountains lay between Castac Lake on the south and the present Grapevine on the north and included what is now the community of Lebec. The rancho is now a part of the Tejon Ranch.

The Tule River Indian Tribe of the Tule River Reservation is a federally recognized tribe of Native Americans. The Tule River Reservation is located in Tulare County, California. The reservation was made up of Yokuts, about 200 Yowlumne, Wukchumnis, and Western Mono and Tübatulabal. Tribal enrollment today is approximately 1,857 with 1,033 living on the Reservation.

The Owens Valley War was fought between 1862 and 1863 by the United States Army and American settlers against the Mono people and their Shoshone and Kawaiisu allies in the Owens Valley of California and the southwestern Nevada border region. The removal of a large number of the Owens River indigenous Californians to Fort Tejon in 1863 was considered the end of the war. Minor hostilities continued intermittently until 1867.

The Stockton–Los Angeles Road, also known as the Millerton Road, Stockton–Mariposa Road, Stockton–Fort Miller Road or the Stockton–Visalia Road, was established about 1853 following the discovery of gold on the Kern River in Old Tulare County. This route between Stockton and Los Angeles followed by the Stockton–Los Angeles Road is described in "Itinerary XXI. From Fort Yuma to Benicia, California", in The Prairie Traveler: A Hand-book for Overland Expeditions by Randolph Barnes Marcy. The Itinerary was derived from the report of Lieutenant R. S. Williamson on his topographical survey party in 1853, that was in search of a railroad route through the interior of California.

Tejon Creek, originally in Spanish Arroyo de Tejon, is a stream in Kern County, California. Its headwaters are located on the western slopes of the Tehachapi Mountains, and it flows northwest into the southern San Joaquin Valley.

The Old Tejon Pass is a mountain pass in the Tehachapi Mountains linking Southern and Central California.

Willow Springs Canyon is a canyon cut by Willow Springs Canyon Wash. Its source is at the head of the canyon in the gap in the Portal Ridge of the Transverse Range, 0.5 miles north of Elizabeth Lake. It is cut into the slope to the northeast into the Antelope Valley, crossing the California Aqueduct. The mouth of the Canyon is 0.25 miles southwest of its confluence with Myrick Canyon Wash which is 300 feet southwest of the intersection of Munz Ranch Road with the Neenach - Fairmont Road in Los Angeles County, California, USA.

The Tejon Indian Tribe is a federally recognized tribe of Kitanemuk, Yokuts, Paiute and Chumash Indigenous people of California.

The California Indian Wars were a series of wars, battles, and massacres between the United States Army, and the Indigenous peoples of California. The wars lasted from 1850, immediately after Alta California, acquired during the Mexican–American War, became the state of California, to 1880 when the last minor military operation on the Colorado River ended the Calloway Affair of 1880.

Castac Lake, also known as Tejon Lake, is a natural saline endorheic, or sink, lake near Lebec, California. The lake is located in the Tehachapi Mountains just south of the Grapevine section of Interstate 5, and within Tejon Ranch. Normal water elevations are 3,482 feet (1,061 m) above sea level.

The Tule River War of 1856 was a conflict where American settlers, and later, California State Militia, and a detachment of the U. S. Army from Fort Miller, fought a six-week war against the Yokuts in the southern San Joaquin Valley.

Between 1851 and 1852, the United States Army forced California's tribes to sign 18 treaties that relinquished each tribe's rights to their traditional lands in exchange for reservations. Due to pressure from California representatives, the Senate repudiated the treaties and ordered them to remain secret. In 1896 the Bureau of American Ethnology report on major native American Indian interactions with the United States Government was the first time the treaties were made public. The report, Indian Land Cessions in the United States (book), compiled by Charles C. Royce, includes the 18 lost treaties between the state's tribes and a map of the reservations. Below is the California segment of the report listing the treaties. The full report covered all 48 states' tribal interactions nationwide with the U.S. government.

Alexander "Alexis" Godey, also called Alec Godey and Alejandro Godey, was a trapper, scout, and mountain man. He was an associate of Jim Bridger and was lead scout for John C. Frémont.