Korean shamanism, also known as musok or Mu-ism, is a religion from Korea. Scholars of religion classify it as a folk religion and sometimes regard it as one facet of a broader Korean vernacular religion distinct from Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism. There is no central authority in control of musok, with much diversity of belief and practice evident among practitioners.

Korean mythology is the group of myths told by historical and modern Koreans. There are two types: the written, literary mythology in traditional histories, mostly about the founding monarchs of various historical kingdoms, and the much larger and more diverse oral mythology, mostly narratives sung by shamans or priestesses (mansin) in rituals invoking the gods and which are still considered sacred today. Bella Myong-wol Dalton-Fenkl and Heinz Insu Fenkl have recently written a book on Korean Mythology published by Thames and Hudson.

Jeju City is the capital of the Jeju Province in South Korea and the largest city on Jeju Island. The city is served by Jeju International Airport.

Stories and practices that are considered part of Korean folklore go back several thousand years. These tales derive from a variety of origins, including Shamanism, Confucianism, Buddhism, and more recently Christianity.

Jeju, often called Jejueo or Jejuan in English-language scholarship, is a Koreanic language originally from Jeju Island, South Korea. It is not mutually intelligible with mainland Korean dialects. While it was historically considered a divergent Jeju dialect of the Korean language, it is increasingly referred to as a separate language in its own right. It is declining in usage and was classified by UNESCO in 2010 as critically endangered, the highest level of language endangerment possible. Revitalization efforts are ongoing.

Shamanic music is ritualistic music used in religious and spiritual ceremonies associated with the practice of shamanism. Shamanic music makes use of various means of producing music, with an emphasis on voice and rhythm. It can vary based on cultural, geographic, and religious influences.

Gut are the rites performed by Korean shamans, involving offerings and sacrifices to gods, spirits and ancestors. They are characterised by rhythmic movements, songs, oracles and prayers. These rites are meant to create welfare, promoting commitment between the spirits and humankind. The major categories of rites are the naerim-gut, the dodang-gut and the ssitgim-gut.

The Chasa Bonpuri, known in other versions as the Chesa Bonpuri or the Cheseo Bonpuri, is a Korean myth of Jeju Island. It is a myth that tells how Gangnim, the death god, came to be. As one of the best-known myths in the Korean peninsula, the Chasa Bonpuri is a characteristic hero epic.

Samsin halmeoni, the Grandmother Samsin, is the goddess of childbirth and fate in Korean mythology.

The bon-puri are Korean shamanic narratives recited in the shamanic rituals of Jeju Island, to the south of the Korean Peninsula. Similar shamanic narratives are known in mainland Korea as well, but are only occasionally referred to as bon-puri.

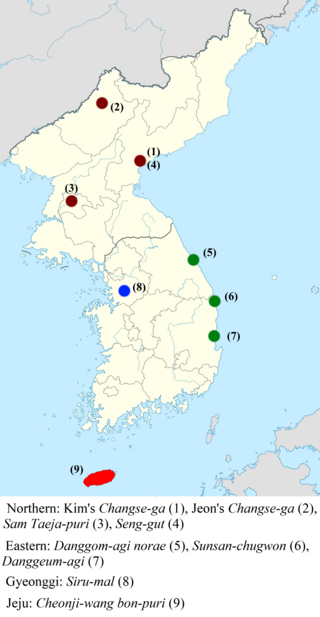

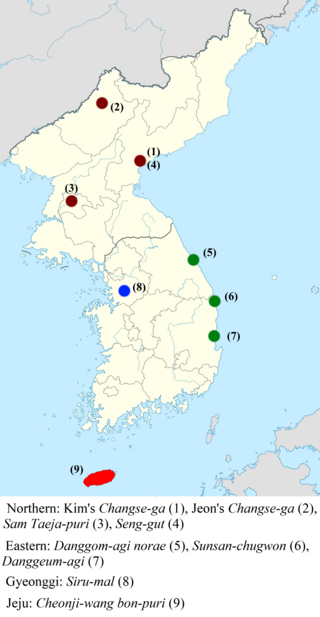

Korean creation narratives are Korean shamanic narratives which recount the mythological beginnings of the universe. They are grouped into two categories: the eight narratives of mainland Korea, which were transcribed by scholars between the 1920s and 1980s, and the Cheonji-wang bon-puri narrative of southern Jeju Island, which exists in multiple versions and continues to be sung in its ritual context today. The mainland narratives themselves are subdivided into four northern and three eastern varieties, along with one from west-central Korea.

The Seng-gut narrative is a Korean shamanic narrative traditionally recited in a large-scale gut ritual in Hamgyong Province, North Korea. It tells of the deeds of one or multiple deities referred to as "sages," beginning from the creation of the world. It combines many stories that appear independently in other regions of Korea into a single extended narrative. In the first story, the deity Seokga usurps the world from the creator, creates animals from deer meat, and destroys a superfluous sun and moon. In the second, the carpenter Gangbangdek builds a palace for the gods, loses a wager to a woman, and becomes the god of the household. In the third and fourth stories, a boy who does not talk until the age of ten becomes the founder of a new Buddhist temple and melts a baby into iron to forge a temple bell. In the fifth, the same priest destroys a rich man for having abused him. Finally, the priest makes his three sons the gods of fertility, ending the story. The narrative has a strong Buddhist influence.

Life replacement narratives or life extension narratives refer to three Korean shamanic narratives chanted during religious rituals, all from different regional traditions of mythology but with a similar core story: the Menggam bon-puri of the Jeju tradition, the Jangja-puri of the Jeolla tradition, and the Honswi-gut narrative of the South Hamgyong tradition. As oral literature, all three narratives exist in multiple versions.

The Song of Dorang-seonbi and Cheongjeong-gaksi is a Korean shamanic narrative recited in the Mangmuk-gut, the traditional funeral ceremony of South Hamgyong Province, North Korea. It is the most ritually important and most popular of the many mythological stories told in this ritual. The Mangmuk-gut is no longer performed in North Korea, but the ritual and the narrative are currently being passed down by a South Korean community descended from Hamgyong refugees.

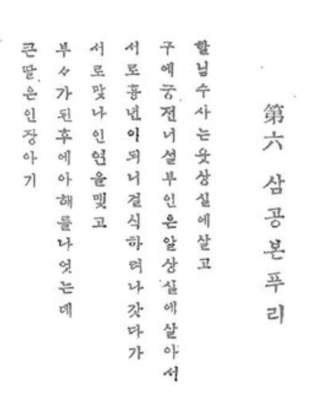

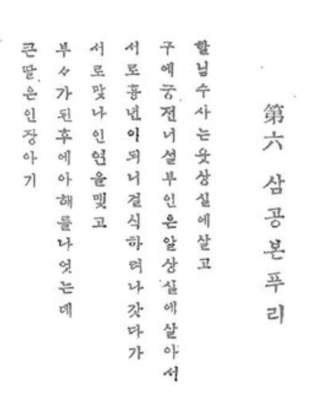

The Samgong bon-puri (Korean: 삼공본풀이) is a Korean shamanic narrative recited in southern Jeju Island, associated with the goddess Samgong. It is among the most important of the twelve general bon-puri, which are the narratives known by all Jeju shamans.

The mengdu, also called the three mengdu and the three mengdu of the sun and moon, are a set of three kinds of brass ritual devices—a pair of knives, a bell, and divination implements—which are the symbols of shamanic priesthood in the Korean shamanism of southern Jeju Island. Although similar ritual devices are found in mainland Korea, the religious reverence accorded to the mengdu is unique to Jeju.

The Naewat-dang shamanic paintings are ten portraits of village patron gods formerly hung at the Naewat-dang shrine, one of the four state-recognized shamanic temples of Jeju Island, now in South Korea. The shrine was destroyed in the nineteenth century, and the works are currently preserved at Jeju National University as a government-designated Important Folklore Cultural Property. They may be the oldest Korean shamanic paintings currently known.

Gongsim is a legendary Korean princess of the Goryeo dynasty said to have been struck with sinbyeong, an illness which can only be cured by initiation into shamanism. According to the myth, she joined the shamanic priesthood at Namsan Mountain in Seoul, and introduced the shamanic religion to Korea or to parts of Korea.

The Durin-gut, also called the Michin-gut and the Chuneun-gut, is the healing ceremony for mental illnesses in the Korean shamanism of southern Jeju Island. While commonly held as late as the 1980s, it has now become very rare due to the introduction of modern psychiatry.

In Korean shamanism, the Chogong bon-puri (Korean: 초공본풀이) is a shamanic narrative whose recitation forms the tenth ritual of the Great Gut, the most sacred sequence of rituals in Jeju shamanism. The Chogong bon-puri is the origin myth of Jeju shamanic religion as a whole, to the point that shamans honor the myth as the "root of the gods" and respond that "it was done that way in the Chogong bon-puri" when asked about the origin of a certain ritual. It also explains the origin of the mengdu, the sacred metal objects that are the source of a Jeju shaman's authority. As with most works of oral literature, multiple versions of the narrative exist. The summary given below is based on the version recited by the high-ranking shaman An Sa-in (1912–1990).