Parkinsonism is a clinical syndrome characterized by tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, and postural instability. Both hypokinetic as well as hyperkinetic features are displayed by Parkinsonism. These are the four motor symptoms found in Parkinson's disease (PD) – after which it is named – dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD), and many other conditions. This set of symptoms occurs in a wide range of conditions and may have many causes, including neurodegenerative conditions, drugs, toxins, metabolic diseases, and neurological conditions other than PD.

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a type of dementia characterized by changes in sleep, behavior, cognition, movement, and regulation of automatic bodily functions. Memory loss is not always an early symptom. The disease worsens over time and is usually diagnosed when cognitive impairment interferes with normal daily functioning. Together with Parkinson's disease dementia, DLB is one of the two Lewy body dementias. It is a common form of dementia, but the prevalence is not known accurately and many diagnoses are missed. The disease was first described on autopsy by Kenji Kosaka in 1976, and he named the condition several years later.

Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is a rare neurodegenerative disorder characterized by tremors, slow movement, muscle rigidity, and postural instability, autonomic dysfunction and ataxia. This is caused by progressive degeneration of neurons in several parts of the brain including the basal ganglia, inferior olivary nucleus, and cerebellum.

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a late-onset neurodegenerative disease involving the gradual deterioration and death of specific volumes of the brain. The condition leads to symptoms including loss of balance, slowing of movement, difficulty moving the eyes, and cognitive impairment. PSP may be mistaken for other types of neurodegeneration such as Parkinson's disease, frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. The cause of the condition is uncertain, but involves the accumulation of tau protein within the brain. Medications such as levodopa and amantadine may be useful in some cases.

Hypokinesia is one of the classifications of movement disorders, and refers to decreased bodily movement. Hypokinesia is characterized by a partial or complete loss of muscle movement due to a disruption in the basal ganglia. Hypokinesia is a symptom of Parkinson's disease shown as muscle rigidity and an inability to produce movement. It is also associated with mental health disorders and prolonged inactivity due to illness, amongst other diseases.

Parkinson-plus syndromes (PPS) are a group of neurodegenerative diseases featuring the classical features of Parkinson's disease with additional features that distinguish them from simple idiopathic Parkinson's disease (PD). Parkinson-plus syndromes are either inherited genetically or occur sporadically.

Corticobasal degeneration (CBD) is a rare neurodegenerative disease involving the cerebral cortex and the basal ganglia. CBD symptoms typically begin in people from 50 to 70 years of age, and typical survival before death is eight years. It is characterized by marked disorders in movement and cognition, and is classified as one of the Parkinson plus syndromes. Diagnosis is difficult, as symptoms are often similar to those of other disorders, such as Parkinson's disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, and dementia with Lewy bodies, and a definitive diagnosis of CBD can only be made upon neuropathologic examination.

Memory disorders are the result of damage to neuroanatomical structures that hinders the storage, retention and recollection of memories. Memory disorders can be progressive, including Alzheimer's disease, or they can be immediate including disorders resulting from head injury.

In the management of Parkinson's disease, due to the chronic nature of Parkinson's disease (PD), a broad-based program is needed that includes patient and family education, support-group services, general wellness maintenance, exercise, and nutrition. At present, no cure for the disease is known, but medications or surgery can provide relief from the symptoms.

Frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17) is an autosomal dominant neurodegenerative tauopathy and Parkinson plus syndrome. FTDP-17 is caused by mutations in the MAPT gene located on the q arm of chromosome 17, and has three cardinal features: behavioral and personality changes, cognitive impairment, and motor symptoms. FTDP-17 was defined during the International Consensus Conference in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1996.

Dopamine-responsive dystonia (DRD) also known as Segawa syndrome (SS), is a genetic movement disorder which usually manifests itself during early childhood at around ages 5–8 years.

Parkinson's disease (PD), or simply Parkinson's, is a long-term neurodegenerative disease of mainly the central nervous system that affects both the motor and non-motor systems of the body. The symptoms usually emerge slowly, and as the disease progresses, non-motor symptoms become more common. Usual symptoms include tremors, slowness of movement, rigidity, and difficulty with balance, collectively known as parkinsonism. Parkinson's disease dementia, falls and neuropsychiatric problems such as sleep abnormalities, psychosis, mood swings, or behavioral changes may arise in advanced stages as well.

The Pacific Udall Center was established in 2009 as a new Morris K. Udall Center of Excellence for Parkinson's Disease Research. It is one of nine Udall Centers across the U.S. that honor former Utah Congressman Morris Udall with a "multidisciplinary research approach to elucidate the fundamental causes of PD [Parkinson's Disease] as well as to improve the diagnosis and treatment of patients with Parkinson's and related neurodegenerative disorders." The Pacific Udall Center is a collaboration among Stanford University, the University of Washington, the VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Oregon Health & Science University, and the Portland VA Medical Center. It is funded by a grant from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Parkinsonian gait is the type of gait exhibited by patients with Parkinson's disease (PD). It is often described by people with Parkinson's as feeling like being stuck in place, when initiating a step or turning, and can increase the risk of falling. This disorder is caused by a deficiency of dopamine in the basal ganglia circuit leading to motor deficits. Gait is one of the most affected motor characteristics of this disorder although symptoms of Parkinson's disease are varied.

Kufor–Rakeb syndrome (KRS) is an autosomal recessive disorder of juvenile onset also known as Parkinson disease-9 (PARK9). It is named after Kufr Rakeb in Irbid, Jordan. Kufor–Rakeb syndrome was first identified in this region in Jordan with a Jordanian couple's 5 children who had rigidity, mask-like face, and bradykinesia. The disease was first described in 1994 by Najim Al-Din et al. The OMIM number is 606693.

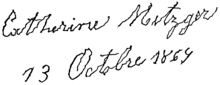

The history of Parkinson's disease expands from 1817, when British apothecary James Parkinson published An Essay on the Shaking Palsy, to modern times. Before Parkinson's descriptions, others had already described features of the disease that would bear his name, while the 20th century greatly improved knowledge of the disease and its treatments. PD was then known as paralysis agitans. The term "Parkinson's disease" was coined in 1865 by William Sanders and later popularized by French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot.

Gene therapy in Parkinson's disease consists of the creation of new cells that produce a specific neurotransmitter (dopamine), protect the neural system, or the modification of genes that are related to the disease. Then these cells are transplanted to a patient with the disease. There are different kinds of treatments that focus on reducing the symptoms of the disease but currently there is no cure.

Gait variability seen in Parkinson's Disorders arise due to cortical changes induced by pathophysiology of the disease process. Gait rehabilitation is focused to harness the adapted connections involved actively to control these variations during the disease progression. Gait variabilities seen are attributed to the defective inputs from the Basal Ganglia. However, there is altered activation of other cortical areas that support the deficient control to bring about a movement and maintain some functional mobility.

Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD) is dementia that is associated with Parkinson's disease (PD). Together with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), it is one of the Lewy body dementias characterized by abnormal deposits of Lewy bodies in the brain.

Rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder and Parkinson's disease is rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD) that is associated with Parkinson's disease. RBC is linked genetically and neuropathologically to α- synuclein, a presynaptic neuronal protein that exerts deleterious effects on neighbouring proteins, leading to neuronal death. This pathology is linked to numerous other neurodegenerative disorders, such as Lewy body dementias, and collectively these disorders are known as synucleinopathies. Numerous reports over the past few years have stated the frequent association of synucleinopathies with REM sleep behaviour disorder (RBD). In particular, the frequent association of RBD with Parkinson's. In the general population the incidence of RBD is around 0.5%, compared to the prevalence of RBD in PD patients, which has been reported to be between 38% and 60%. The diagnosis and symptom onset of RBD typically precedes the onset of motor or cognitive symptoms of PD by a number of years, typically ranging anywhere from 2 to 15 years prior. Hence, this link could provide an important window of opportunity in the implementation of therapies and treatments, that could prevent or slow the onset of PD.