Hugh Binning (1627–1653) was a Scottish philosopher and theologian. He was born in Scotland during the reign of Charles I and was ordained in the (Presbyterian) Church of Scotland. He died in 1653, during the time of Oliver Cromwell and the Commonwealth of England.

The Lord Justice Clerk is the second most senior judge in Scotland, after the Lord President of the Court of Session.

William Douglas, 1st Duke of Queensberry PC, also 3rd Earl of Queensberry and 1st Marquess of Queensberry, was a Scottish politician.

Lord Neill Campbell was a Scottish nobleman who served as Deputy Governor of East New Jersey during 1686, succeeding Gawen Lawrie.

John Nisbet (1627–1685) was a Scottish covenanter who was executed for participating in the insurgency at Bothwell Brig and earlier conflicts and for attending a conventicle. He took an active and prominent part in the struggles, of the Covenanters for civil and religious liberty. He was wounded and left for dead at Pentland in 1666 but lived and fought as a captain at Bothwell Bridge, in 1679. He was subsequently seized and executed as a rebel. He was a descendant of Murdoch Nisbet, a Lollard who translated the Bible into the Scots language.

Sir Robert Baird (1630-1697) was a Scottish merchant, landowner, and investor in colonial enterprise in the Province of Carolina.

Greyfriars Kirkyard is the graveyard surrounding Greyfriars Kirk in Edinburgh, Scotland. It is located at the southern edge of the Old Town, adjacent to George Heriot's School. Burials have been taking place since the late 16th century, and a number of notable Edinburgh residents are interred at Greyfriars. The Kirkyard is operated by City of Edinburgh Council in liaison with a charitable trust, which is linked to but separate from the church. The Kirkyard and its monuments are protected as a category A listed building.

George Scot or Scott of Pitlochie, Fife was a Scottish writer on colonisation in North America.

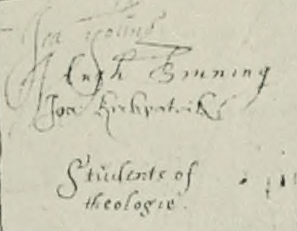

John Stewart was a 17th-century Scottish minister.

Sir George Campbell of Cessnock in Ayrshire was a 17th-century statesman. His lineage was from the Campbells of Loudoun. His father was Sir Hugh Campbell and his mother was Elizabeth Campbell.

John Dickson was a 17th-century minister from Rutherglen in Scotland. He was a Covenanting field-preacher and a close associate of John Blackadder. For preaching outdoors without a licence he was imprisoned on the Bass Rock from 1 September 1680 to 8 October 1686.

Rev Thomas Hog of Kiltearn (1628–1692) was a controversial 17th century Scottish minister.

John Rae was the son of William Rae, burgess of Edinburgh. He served heir 7 February 1666. He was educated at the University of Glasgow and graduated with an M.A. in 1651.

Alexander Dunbar was a Covenanting field preacher and school teacher. He was imprisoned on the Bass Rock for about a year between 1685 and 1686.

James Fithie was a chaplain at Trinity Hospital in Edinburgh. He was imprisoned on the Bass Rock for about a year between 1685 and 1686.

John Greig was a Presbyterian minister from Scotland.

Peter Kid was a 17th-century Presbyterian minister. He was possibly a native of Fife.

Thomas Ross of Nether Pitkerrie, was born about 1614. He was the son of George Ross of Nether Pitkerrie. He continued in Kincardine after the establishment of prelacy and owes his leaving to a meeting with John M'Gilligan.

William Spence was a Scottish schoolmaster in Fife. In the month of May 1685, he was summoned to appear before the Privy Council. Phillimore says he "had committed the offence of teaching his pupils the doctrines of Presbyterianism, and attending the forbidden conventicles." Dickson says he "was committed to the Bass where he remained for more than a year, when he petitioned for his liberty on the ground of ill-health." He was sent to the Bass Rock at the same time as Peter Kid and had fourteen months of imprisonment. On the 20th of July 1686, “My Lords ” agreed to his release “upon his finding caution to compear before the Council, when cited; and, in the meantime, to live peaceably and not to keep a school, under a penalty of five thousand merks, Scots money, in case of failure.” He was liberated along with John Greg. After he was set free he had to periodically reappear before the Council to retain his liberty.

Hugh Campbell, 3rd Earl of Loudoun, KT, PC was a Scottish landowner, peer, and statesman.