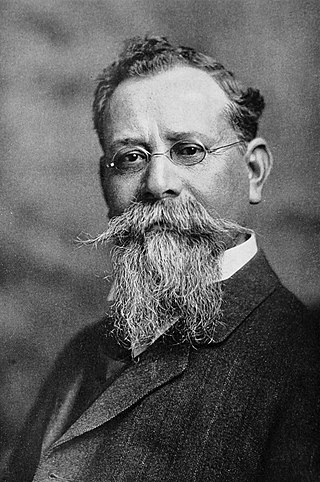

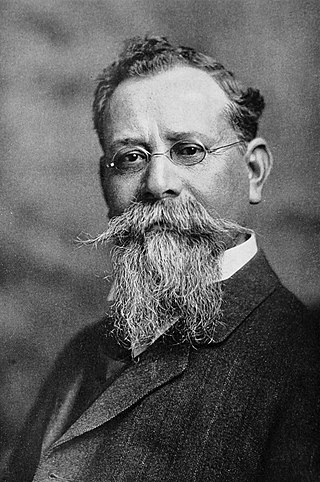

José Venustiano Carranza de la Garza was a Mexican land owner and politician who served as President of Mexico from 1917 until his assassination in 1920, during the Mexican Revolution. He was previously Mexico's de facto head of state as Primer Jefe of the Constitutionalist faction from 1914 to 1917, and previously served as a senator and governor for Coahuila. He played the leading role in drafting the Constitution of 1917 and maintained Mexican neutrality in World War I.

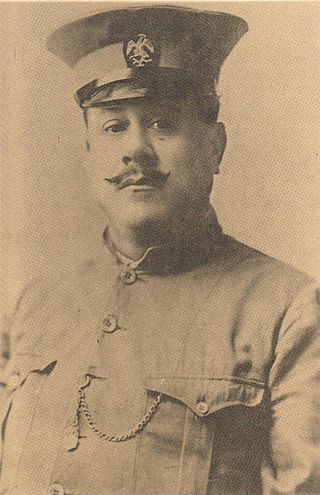

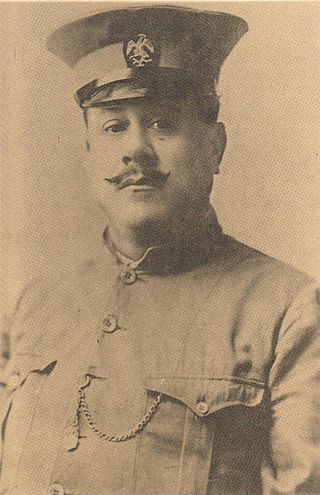

Álvaro Obregón Salido was a Mexican military general and politician who served as the 46th President of Mexico from 1920 to 1924. Obregón was re-elected to the presidency in 1928 but was assassinated before he could take office.

Plutarco Elías Calles was a Mexican soldier and politician who served as President of Mexico from 1924 to 1928. After the assassination of Álvaro Obregón, Elías Calles founded the Institutional Revolutionary Party and held unofficial power as Mexico's de facto leader from 1929 to 1934, a period known as the Maximato. Previously, he served as a general in the Constitutional Army, as Governor of Sonora, Secretary of War, and Secretary of the Interior. During the Maximato, he served as Secretariat of Public Education, Secretary of War again, and Secretary of the Economy. During his presidency, he implemented many left-wing populist and secularist reforms, opposition to which sparked the Cristero War.

Emilio Cándido Portes Gil was President of Mexico from 1928 to 1930, one of three to serve out the six-year term of President-elect General Álvaro Obregón, who had been assassinated in 1928. Since the Mexican Constitution of 1917 forbade re-election of a serving president, incumbent President Plutarco Elías Calles could not formally retain the presidency. Portes Gil replaced him, but Calles, the "Jefe Máximo", retained effective political power during what is known as the Maximato.

Ignacio Bonillas Fraijo was a Mexican diplomat. He was a Mexican ambassador to the United States and held a degree in mine engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He was tapped by President Venustiano Carranza as his successor in the 1920 presidential elections, but the revolt of three Sonoran revolutionary generals overthrew Carranza before those elections took place.

Martín Luis Guzmán Franco was a Mexican novelist and journalist. Along with Mariano Azuela and Nellie Campobello, he is considered a pioneer of the revolutionary novel, a genre inspired by the experiences of the Mexican Revolution of 1910. He spent periods in exile in the United States and Spain. He founded newspapers, weekly magazines, and publishing companies. In 1958, he was awarded Mexico's National Prize in Literature.

List of governors of the Mexican state of Sonora since 1911:

Events in the year 1920 in Mexico.

Luis Morones Negrete, also known as Luis Napoleón Morones, was a Mexican major union leader, politician, and government official. He was a pragmatic politician who experienced a rapid rise to prominence from modest roots and made strategic alliances. He served as Secretary General of the Regional Confederation of Mexican Workers and as secretary of economy under President Plutarco Elías Calles, 1924-1928. He is considered the "most important union leader of the 1920s...and undoubtedly decisive in Mexico's post-Revolutionary reconstruction." He was criticized for tying the labor movement closely to the national government and his displays of wealth were unseemly. He fell from power following the successful 1928 presidential run by Alvaro Obregón, who was assassinated before being inaugurated.

Felipe Adolfo de la Huerta Marcor was a Mexican politician, the 45th President of Mexico from 1 June to 30 November 1920, following the overthrow of Mexican president Venustiano Carranza, with Sonoran generals Alvaro Obregón and Plutarco Elías Calles under the Plan of Agua Prieta. He is considered "an important figure among Constitutionalists during the Mexican Revolution."

Pascual Ortiz Rubio served as President of Mexico from 1930 to 1932. He was one of three presidents to serve out the six-year term (1928–1934) of assassinated president-elect Álvaro Obregón, while former president Plutarco Elías Calles retained power in a period known as the Maximato. Calles was so blatantly in control of the government that Ortiz Rubio resigned the presidency in protest in September 1932.

Gen. Benjamín Guillermo Hill Salido was a military commander during the Mexican Revolution. He was a cousin of revolutionary general and later president Álvaro Obregón Salido, whom he supported from the beginning of his rise to power. He was called "Obregón's lost right arm," alluding to the arm his cousin lost in the 1915 Battle of Celaya, defeating General Pancho Villa.

In the history of Mexico, the Plan of Agua Prieta was a manifesto, or plan, that articulated the reasons for rebellion against the government of Venustiano Carranza. Three revolutionary generals from Sonora, Álvaro Obregón, Plutarco Elías Calles, and Adolfo de la Huerta, often called the Sonoran Triumvirate, or the Sonoran Dynasty, rose in revolt against the civilian government of Carranza. It was proclaimed by Obregón on 22 April 1920, in English and 23 April in Spanish in the northern border city of Agua Prieta, Sonora.

The Maximato was a transitional period in the historical and political development of Mexico from 1928 to 1934. Named after former president Plutarco Elías Calles's sobriquet el Jefe Máximo, the Maximato was the period that Calles continued to exercise power and exert influence without holding the presidency. The six-year period was the term that President-elect Alvaro Obregón would have served if he had not been assassinated immediately after the July 1928 elections. There needed to be some kind of political solution to the presidential succession crisis. Calles could not hold the presidency again because of restrictions on re-election without an interval out of power, but he remained the dominant figure in Mexico.

Guaymas Municipality is a municipality in the Mexican state of Sonora in north-western Mexico. In 2015, the municipality had a total population of 158,046. The municipal seat is the city of Guaymas.

This article details the history of Sonora. The Free and Sovereign State of Sonora is one of 31 states that, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 72 municipalities; the capital city is Hermosillo. Sonora is located in Northwest Mexico, bordered by the states of Chihuahua to the east, Baja California to the northwest and Sinaloa to the south. To the north, it shares the U.S.–Mexico border with the states of Arizona and New Mexico, and on the west has a significant share of the coastline of the Gulf of California.

Salvador Alvarado Rubio was a general and politician during the Mexican Revolution. He was serving in the Constitutionalist Army under President Carranza. Alvarado was the Governor of Yucatán from February 1915 to November, 1918, and Secretary of the Treasury under President de la Huerta. There is a Salvador Alvarado Municipality in the State of Sinaloa, where he was born, named in his honor.

José Manuel Puig Casauranc was a Mexican politician, diplomat and journalist who served as Secretary of Public Education, Secretary of Industry, Commerce and Labor, Secretary of Foreign Affairs and federal legislator in both the Senate and Chamber of Deputies. As a key adviser to President Plutarco Elías Calles (1924–28), he is credited with drafting Calles's speech to Congress following the assassination of President-elect Alvaro Obregón declaring the end of the age of caudillos and the start of rule of institutions and laws.

The following lists events that happened in 1924 in the United Mexican States.

José Santiago Healy Brennan was a business person, revolutionary, journalist, columnist and contributor to various Mexican newspapers. During his political exile in 1924, he founded the newspaper ECO de México in Los Angeles; and in 1942 he acquired and modernized the Sonoran newspaper known as El Imparcial and El Regional de Hermosillo.