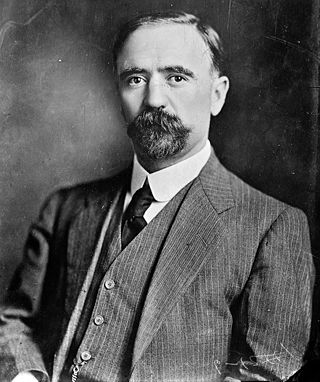

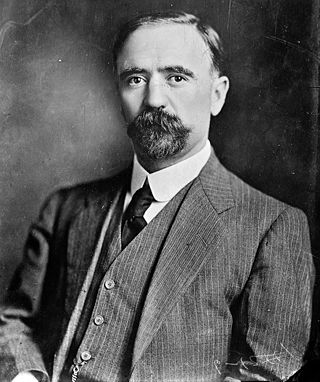

Francisco Ignacio Madero González was a Mexican businessman, revolutionary, writer and statesman, who served as the 37th president of Mexico from 1911 until he was deposed in a coup d'état in February 1913 and assassinated. He came to prominence as an advocate for democracy and as an opponent of President and de facto dictator Porfirio Díaz. After Díaz claimed to have won the fraudulent election of 1910 despite promising a return to democracy, Madero started the Mexican Revolution to oust Díaz. The Mexican revolution would continue until 1920, well after Madero and Díaz's deaths, with hundreds of thousands dead.

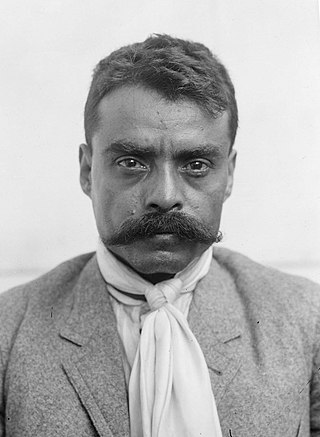

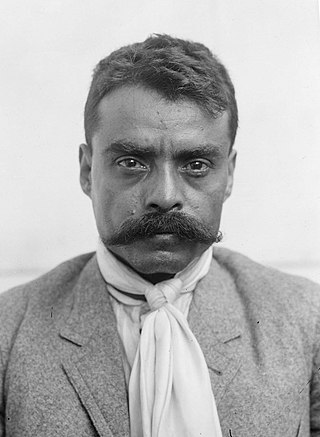

Emiliano Zapata Salazar was a Mexican revolutionary. He was a leading figure in the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1920, the main leader of the people's revolution in the Mexican state of Morelos, and the inspiration of the agrarian movement called Zapatismo.

Francisco "Pancho" Villa was a Mexican revolutionary and general in the Mexican Revolution. He was a key figure in the revolutionary movement that forced out President Porfirio Díaz and brought Francisco I. Madero to power in 1911. When Madero was ousted by a coup led by General Victoriano Huerta in February 1913, Villa joined the anti-Huerta forces in the Constitutionalist Army led by Venustiano Carranza. After the defeat and exile of Huerta in July 1914, Villa broke with Carranza. Villa dominated the meeting of revolutionary generals that excluded Carranza and helped create a coalition government. Emiliano Zapata and Villa became formal allies in this period. Like Zapata, Villa was strongly in favor of land reform, but did not implement it when he had power. At the height of his power and popularity in late 1914 and early 1915, the U.S. considered recognizing Villa as Mexico's legitimate authority.

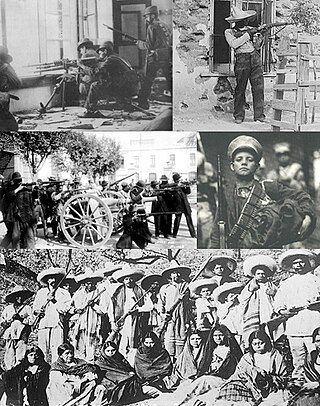

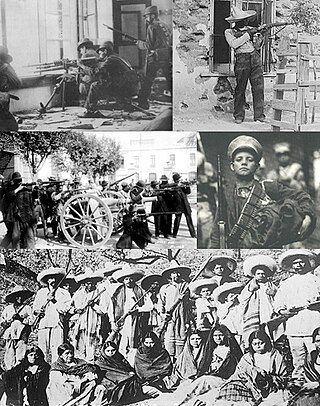

The Mexican Revolution was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from 20 November 1910 to 1 December 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history" and resulted in the destruction of the Federal Army, its replacement by a revolutionary army, and the transformation of Mexican culture and government. The northern Constitutionalist faction prevailed on the battlefield and drafted the present-day Constitution of Mexico, which aimed to create a strong central government. Revolutionary generals held power from 1920 to 1940. The revolutionary conflict was primarily a civil war, but foreign powers, having important economic and strategic interests in Mexico, figured in the outcome of Mexico's power struggles; the U.S. involvement was particularly high. The conflict led to the deaths of around one million people, mostly noncombatants.

José Victoriano Huerta Márquez was a general in the Mexican Federal Army and 39th President of Mexico, who came to power by coup against the democratically elected government of Francisco I. Madero with the aid of other Mexican generals and the U.S. Ambassador to Mexico. His violent seizure of power set off a new wave of armed conflict in the Mexican Revolution.

José Venustiano Carranza de la Garza was a Mexican land owner and politician who served as President of Mexico from 1917 until his assassination in 1920, during the Mexican Revolution. He was previously Mexico's de facto head of state as Primer Jefe of the Constitutionalist faction from 1914 to 1917, and previously served as a senator and governor for Coahuila. He played the leading role in drafting the Constitution of 1917 and maintained Mexican neutrality in World War I.

Álvaro Obregón Salido was a Mexican military general and politician who served as the 46th President of Mexico from 1920 to 1924. Obregón was re-elected to the presidency in 1928 but was assassinated at La Bombilla restaurant before he could take office.

Francisco Sebastián Carvajal y Gual, sometimes spelled Carbajal was a Mexican lawyer and politician who served briefly as president in 1914, during the Mexican Revolution. In his role as foreign minister, he succeeded Victoriano Huerta as president upon the latter's resignation.

Eulalio Gutiérrez Ortiz was a general in the Mexican Revolution from state of Coahuila. He is most notable for his election as provisional president of Mexico during the Aguascalientes Convention and led the country for a few months between 6 November 1914 and 16 January 1915. The Convention was convened by revolutionaries who had successfully ousted the regime of Victoriano Huerta after more than a year of conflict. Gutiérrez rather than "First Chief" Venustiano Carranza was chosen president of Mexico and a new round of violence broke out as revolutionary factions previously united turned against each other. "The high point of Gutiérrez's career occurred when he moved with the Conventionist army to shoulder the responsibilities of his new office [of president]." Gutiérrez's government was weak and he could not control the two main generals of the Army of the Convention, Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata. Gutiérrez moved the capital of his government from Mexico City to San Luis Potosí. He resigned as president and made peace with Carranza. He went into exile in the United States, but later returned to Mexico. He died in 1939, outliving many other major figures of the Mexican Revolution.

Roque Victoriano González Garza was a Mexican general and politician who served as acting President of Mexico from January to June 1915. He was appointed by the Convention of Aguascalientes during the Mexican Revolution, and had previously been an important advisor to President Francisco Madero and a member of the Chamber of Deputies. He was later a founder of the anti-communist, xenophobic, antisemitic, nationalist Revolutionary Mexicanist Action party and its leader from 1933 to 1934.

The Plan of Ayala was a document drafted by revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata during the Mexican Revolution. In it, Zapata denounced President Francisco Madero for his perceived betrayal of the revolutionary ideals embodied in Madero's Plan de San Luis Potosí, and set out his vision of land reform. The Plan was first proclaimed on November 28, 1911, in the town of Ayala, Morelos, and was later amended on June 19, 1914. The Plan of Ayala was a key document during the revolution and influenced land reform in Mexico during the 1920s and 1930s. It was the fundamental text of the Zapatistas.

The Liberation Army of the South was a guerrilla force led for most of its existence by Emiliano Zapata that took part in the Mexican Revolution from 1911 to 1920. During that time, the Zapatistas fought against the national governments of Porfirio Díaz, Francisco Madero, Victoriano Huerta, and Venustiano Carranza. Their goal was rural land reform, specifically reclaiming communal lands stolen by hacendados in the period before the revolution. Although rarely active outside their base in Morelos, they allied with Pancho Villa to support the Conventionists against the Carrancistas. After Villa's defeat, the Zapatistas remained in open rebellion. It was only after Zapata's 1919 assassination and the overthrow of the Carranza government that Zapata's successor, Gildardo Magaña, negotiated peace with President Álvaro Obregón.

In Mexican history, a plan was a declaration of principles announced in conjunction with a rebellion, usually armed, against the central government of the country. Mexican plans were often more formal than the pronunciamientos that were their equivalent elsewhere in Spanish America and Spain. Some were as detailed as the United States Declaration of Independence. Some plans simply announced that the current government was null and void and that the signer of the plan was the new president.

The Constitutional Army, also known as the Constitutionalist Army, was the army that fought against the Federal Army, and later, against the Villistas and Zapatistas during the Mexican Revolution. It was formed in March 1913 by Venustiano Carranza, so-called "First-Chief" of the army, as a response to the murder of President Francisco I. Madero and Vice President José María Pino Suárez by Victoriano Huerta during La Decena Trágica of 1913, and the resulting usurpation of presidential power by Huerta.

The Constitutionalists were a faction in the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920). They were formed in 1914 as a response to the assassination of Francisco Madero and Victoriano Huerta's coup d'etat. Also known as Carrancistas, taking that name from their leader, Venustiano Carranza the governor Coahuila. The Constitutionalists played the leading role in defeating the Mexican Federal Army on the battlefield. Carranza, a centrist liberal attracted Mexicans across various political ideologies to the Constitutionalist cause. Constitutionalists consisted of mainly middle-class urbanites, liberals, and intellectuals who desired a democratic constitution under the guidelines "Mexico for Mexicans" and Mexican nationalism. Their support for democracy in Mexico, caught the attention of the United States who aided their cause. In 1914, the United States occupied Mexico's largest port in Veracruz in an attempt to starve Huerta's government of customs revenue. They crafted and enforced the Mexican Constitution of 1917 which remains in force today. Following the defeat of General Huerta, the Constitutionalists outmaneuvered their former revolutionary allies Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa becoming the victorious faction of the Mexican Revolution. However the Constitutionalists were divided amongst themselves and Carranza was assassinated in 1920. He was succeeded by General Álvaro Obregón who began enforcing the 1917 constitution and calming revolutionary tensions. His assassination and the subsequent power vacuum this created spurred his successor, Plutarco Elías Calles to create the National Revolutionary Party (PNR) which would hold uninterrupted political power in Mexico until 2000.

The Conventionists were a faction led by Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata which grew in opposition to the Constitutionalists of Venustiano Carranza and Álvaro Obregón during the Mexican Revolution. It was named for the Convention of Aguascalientes of October to November 1914.

The Teoloyucan Treaties were signed on August 13, 1914, at Teoloyucan, State of Mexico, Mexico between the revolutionary army and forces loyal to Victoriano Huerta. The Constitutionalist Army of First Chief Venustiano Carranza was represented by Álvaro Obregón and Lucio Blanco. The Federal Army was represented by General Gustavo A. Salas and Admiral Othón P. Blanco, while Mexico City was represented by Eduardo Iturbe. The treaties established the surrender of the Federal Army and its dissolution.

The Morelos Commune was the political and economic system established in the Mexican state of Morelos between 1913 and 1917. Led by Emiliano Zapata, the people of Morelos implemented a series of wide-reaching social reforms based on the proposals laid out in the Plan of Ayala.

In the history of Mexico, the Pact of Torreón was a plan drawn up during the Mexican Revolution in early July 1914 by generals of the Constitutionalist Army in the important northern city of Torreón, Coahuila. The pact was framed as a modification of Venustiano Carranza’s 1913 Plan of Guadalupe, which was a narrow political plan. The pact called for a constitutional convention to revise the 1857 Mexican Constitution. It excluded commanders in the Constitutionalist Army from running for the presidency of the republic in the future. It called for the end of the Federal Army, at the time commanded by former general, now president of Mexico, Victoriano Huerta. The Pact of Torreón added to Plan of Guadalupe language that was more radical than Carranza’s, prompting Carranza to issue "Additions to the Plan of Guadalupe".