Luis Echeverría Álvarez was a Mexican lawyer, academic, and politician affiliated with the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) who served as the 57th president of Mexico from 1970 to 1976. Previously, Echeverría was Secretary of the Interior from 1963 to 1969. He was the longest-lived president in Mexican history and the first to reach the age of 100.

The Dirty War is the name used by the military junta or civic-military dictatorship of Argentina for its period of state terrorism in Argentina from 1974 to 1983. During this campaign, military and security forces and death squads in the form of the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance hunted down any political dissidents and anyone believed to be associated with socialism, left-wing Peronism, or the Montoneros movement.

Julio César Méndez Montenegro was a Guatemalan academic who served as the 34th president of Guatemala from July 1966 to July 1970. Mendez was elected on a platform promising democratic reforms and the curtailment of military power. The only civilian to occupy Guatemala's presidency during the long period of military rule between 1954 and 1986. Nevertheless, his election and swearing in was considered a major turning point for the long military-led Guatemala. He was the first cousin of César Montenegro Paniagua whose kidnapping, torture and murder during the Julio César Méndez presidency is rumored to have been undertaken with presidential sanction.

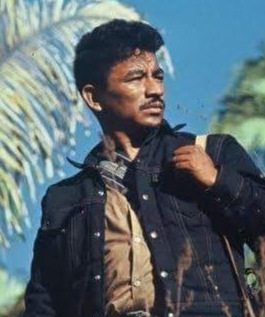

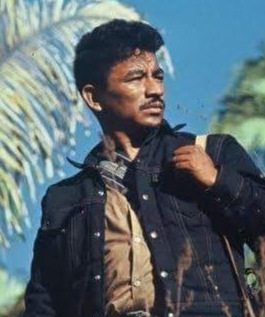

Lucio Cabañas Barrientos was a Mexican social leader, schoolteacher, union leader, and guerrilla leader who founded the social and political movement Party of the Poor in 1967. Under his leadership, the party later became a guerrilla organization that was active in the Sierra Madre del Sur mountain range of Guerrero.

The Popular Revolutionary Army is a far-left guerrilla movement in Mexico. Though it operates mainly in the state of Guerrero, it has conducted operations in other southern Mexican states, including Oaxaca, Chiapas, Guanajuato, Tlaxcala and Veracruz.

The military history of Mexico encompasses armed conflicts within that nation's territory, dating from before the arrival of Europeans in 1519 to the present era. Mexican military history is replete with small-scale revolts, foreign invasions, civil wars, indigenous uprisings, and coups d'état by disgruntled military leaders. Mexico's colonial-era military was not established until the eighteenth century. After the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire in the early sixteenth century, the Spanish crown did not establish on a standing military, but the crown responded to the external threat of a British invasion by creating a standing military for the first time following the Seven Years' War (1756–63). The regular army units and militias had a short history when in the early 19th century, the unstable situation in Spain with the Napoleonic invasion gave rise to an insurgency for independence, propelled by militarily untrained men fighting for the independence of Mexico. The Mexican War of Independence (1810–21) saw royalist and insurgent armies battling to a stalemate in 1820. That stalemate ended with the royalist military officer turned insurgent, Agustín de Iturbide persuading the guerrilla leader of the insurgency, Vicente Guerrero, to join in a unified movement for independence, forming the Army of the Three Guarantees. The royalist military had to decide whether to support newly independent Mexico. With the collapse of the Spanish state and the establishment of first a monarchy under Iturbide and then a republic, the state was a weak institution. The Roman Catholic Church and the military weathered independence better. Military men dominated Mexico's nineteenth-century history, most particularly General Antonio López de Santa Anna, under whom the Mexican military were defeated by Texas insurgents for independence in 1836 and then the U.S. invasion of Mexico (1846–48). With the overthrow of Santa Anna in 1855 and the installation of a government of political liberals, Mexico briefly had civilian heads of state. The Liberal Reforms that were instituted by Benito Juárez sought to curtail the power of the military and the church and wrote a new constitution in 1857 enshrining these principles. Conservatives comprised large landowners, the Catholic Church, and most of the regular army revolted against the Liberals, fighting a civil war. The Conservative military lost on the battlefield. But Conservatives sought another solution, supporting the French intervention in Mexico (1862–65). The Mexican army loyal to the liberal republic were unable to stop the French army's invasion, briefly halting it with a victory at Puebla on 5 May 1862. Mexican Conservatives supported the installation of Maximilian Hapsburg as Emperor of Mexico, propped up by the French and Mexican armies. With the military aid of the U.S. flowing to the republican government in exile of Juárez, the French withdrew its military supporting the monarchy and Maximilian was caught and executed. The Mexican army that emerged in the wake of the French Intervention was young and battle tested, not part of the military tradition dating to the colonial and early independence eras.

The Liga Comunista 23 de Septiembre, or LC23S, was a Marxist-Leninist and later council communist urban guerrilla movement that emerged in Mexico in the early 1970s. The result of the merging of various armed revolutionary organizations active in Mexico prior to 1974, with the objective of creating a united front to combat the Mexican government; the name was chosen to commemorate an unsuccessful guerrilla assault on the barracks of Ciudad Madera in the northern state of Chihuahua led by former schoolteacher Arturo Gámiz and the People's Guerrilla Group on September 23, 1965. The LC23S' militancy was made up mainly of young disenfranchised university students who saw any opportunity of a peaceful political transformation die in the aftermath of the 1968 student movement and then to be buried in the violent crackdown of 1971. Its long term objective was the “elimination of the capitalist system and bourgeois democracy, which would be replaced by a socialist republic and the dictatorship of the proletariat”.

Muerte a Secuestradores or MAS, was a Colombian paramilitary group and a private army supported by drug cartels, U.S. corporations, Colombian politicians, and wealthy landowners during the 1980s to protect their economic interests and fight kidnapping. Muerte a Secuestradores assassinated political opponents and community organizers, and waged counterinsurgency warfare against guerrilla movements such as the FARC-EP and the M-19.

Dirty wars are offensives conducted by regimes against their dissidents, marked by the use of torture and forced disappearance of civilians.

The Mexican Movement of 1968, also known as the Mexican Student Movement was a social movement composed of a broad coalition of students from Mexico's leading universities that garnered widespread public support for political change in Mexico. A major factor in its emergence publicly was the Mexican government's lavish spending to build Olympic facilities for the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. The movement demanded greater political freedoms and an end to the authoritarianism of the PRI regime, which had been in power since 1929.

Costa Grande of Guerrero is a sociopolitical region located in the Mexican state of Guerrero, along the Pacific Coast. It makes up 325 km (202 mi) of Guerrero's approximately 500 km (311 mi) coastline, extending from the Michoacán border to the Acapulco area, wedged between the Sierra Madre del Sur and the Pacific Ocean. Acapulco is often considered part of the Costa Grande; however, the government of the state classifies the area around the city as a separate region. The Costa Grande roughly correlates to the Cihuatlán province of the Aztec Empire, which was conquered between 1497 and 1504. Before then, much of the area belonged to a dominion under the control of the Cuitlatecs, but efforts by both the Purépecha Empire and Aztec Empire to expand into this area in the 15th century brought this to an end. Before the colonial period, the area had always been sparsely populated with widely dispersed settlements. The arrival of the Aztecs caused many to flee and the later arrival of the Spanish had the same effect. For this reason, there are few archeological remains; however, recent work especially at La Soledad de Maciel has indicated that the cultures here are more important than previously thought. Today, the area economically is heavily dependent on agriculture, livestock, fishing and forestry, with only Zihuatanejo and Ixtapa with significantly developed infrastructure for tourism. The rest of the coast has been developed spottily, despite some government efforts to promote the area.

Genaro Vázquez Rojas was a Mexican school teacher, organiser, militant, and guerrilla fighter.

Legislative elections were held in Mexico on 1 July 1979. The Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) won 296 of the 400 seats in the Chamber of Deputies. Voter turnout was 49%.

Mario Arturo Acosta Chaparro Escápite was a Mexican Army general who was shot dead in an incident in Mexico City. He had been incarcerated in the year 2000 for allegedly having ties with the Mexican criminal group known as the Juárez Cartel; he was later released in 2007 for lack of evidences against him. Acosta was also accused of 143–500 disappearances during Mexico's "Dirty War" in the 1970s.

Guerra sucia may refer to:

Israel Nogueda Otero was a Mexican politician, economist and member of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). Nogueda served as the Municipal President of Acapulco municipality from 1969 to 1971 and the Governor of Guerrero from 1971 until 1975.

Ángel Heladio Aguirre Rivero is a Mexican politician affiliated with the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) and formerly with the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). He served as governor of Guerrero from 2011 until he stepped down on 23 October 2014. He has been a member of both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. He served as interim governor of Guerrero between 1996 and 1999. He served a later term as governor of Guerrero between 2011 and 2014. In October 2014 he resigned after protests related to the Iguala mass kidnapping.

The Party of the Poor was a left-wing political movement and militant group in Mexico operating between 1967 and 1974. Led by the rural schoolteacher Lucio Cabañas, the PdlP – through its armed wing, the Peasants' Justice Brigade – waged guerrilla warfare against the Mexican government in the mountains of Guerrero.

The GeneralDirectorate of Political and Social Investigations, was one of the two main domestic intelligence and security service of the United Mexican States. Created in 1918 as Sección Primera, under President Venustiano Carranza's administration, it reported directly to the office of the president. After the consolidation of the post-revolutionary Mexican political structure, and the rise of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, its jurisdiction changed to that of the Mexican Secretariat of the Interior. In 1985, following a political crisis involving the death DEA agent, the DGIPS was combined with its sister agency, the Federal Security Directorate, creating the Center for Research and National Security which is active to this day.

On 18 May 1967, Mexican police shot protesters in Atoyac de Álvarez, Guerrero killing at least five people, in what is referred to as the Atoyac massacre. It was part of a series of disappearances, cases of torture, extrajudicial executions and other forms of repression employed systematically against left-wing groups from the 1960s to the 1980s, in what became known as the Mexican Dirty War.