The Middle East is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The United Arab Republic was a sovereign state in the Middle East from 1958 until 1961. It was initially a short-lived political union between Egypt and Syria from 1958 until Syria seceded from the union following the 1961 Syrian coup d'état. Egypt continued to be known officially as the United Arab Republic until it was formally dissolved by Anwar Sadat in September 1971.

The Suez Crisis also known as the Second Arab–Israeli War, the Tripartite Aggression in the Arab world and as the Sinai War in Israel, was a British–French–Israeli invasion of Egypt in 1956. Israel invaded on 29 October, having done so with the primary objective of re-opening the Straits of Tiran and the Gulf of Aqaba as the recent tightening of the eight-year-long Egyptian blockade further prevented Israeli passage. After issuing a joint ultimatum for a ceasefire, the United Kingdom and France joined the Israelis on 5 November, seeking to depose Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser and regain control of the Suez Canal, which Nasser had earlier nationalised by transferring administrative control from the foreign-owned Suez Canal Company to Egypt's new government-owned Suez Canal Authority. Shortly after the invasion began, the three countries came under heavy political pressure from both the United States and the Soviet Union, as well as from the United Nations, eventually prompting their withdrawal from Egypt. Israel's four-month-long occupation of the Egyptian-occupied Gaza Strip and Egypt's Sinai Peninsula enabled it to attain freedom of navigation through the Straits of Tiran, but the Suez Canal was closed from October 1956 to March 1957.

The Eisenhower Doctrine was a policy enunciated by Dwight D. Eisenhower on January 5, 1957, within a "Special Message to the Congress on the Situation in the Middle East". Under the Eisenhower Doctrine, a Middle Eastern country could request American economic assistance or aid from U.S. military forces if it was being threatened by armed aggression. Eisenhower singled out the Soviet threat in his doctrine by authorizing the commitment of U.S. forces "to secure and protect the territorial integrity and political independence of such nations, requesting such aid against overt armed aggression from any nation controlled by international communism." The phrase "international communism" made the doctrine much broader than simply responding to Soviet military action. A danger that could be linked to communists of any nation could conceivably invoke the doctrine.

The 1958 Lebanon crisis was a political crisis in Lebanon caused by political and religious tensions in the country that included an American military intervention, which lasted for around three months until President Camille Chamoun, who had requested the assistance, completed his term as president of Lebanon. American and Lebanese government forces occupied the Port of Beirut and Beirut International Airport. With the crisis over, the United States withdrew.

The Cold War (1953–1962) refers to the period in the Cold War between the end of the Korean War in 1953 and the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. It was marked by tensions and efforts at détente between the US and Soviet Union.

Shukri al-Quwatli was the first president of post-independence Syria, in 1943. He began his career as a dissident working towards the independence and unity of the Ottoman Empire's Arab territories and was consequently imprisoned and tortured for his activism. When the Kingdom of Syria was established, Quwatli became a government official, though he was disillusioned with monarchism and co-founded the republican Independence Party. Quwatli was immediately sentenced to death by the French who took control over Syria in 1920. Afterward, he based himself in Cairo where he served as the chief ambassador of the Syrian-Palestinian Congress, cultivating particularly strong ties with Saudi Arabia. He used these connections to help finance the Great Syrian Revolt (1925–1927). In 1930, the French authorities pardoned Quwatli and thereafter, he returned to Syria, where he gradually became a principal leader of the National Bloc. He was elected president of Syria in 1943 and oversaw the country's independence three years later.

After the Russian Revolution, in which the Bolsheviks took over parts of the collapsing Russian Empire in 1918, they faced enormous odds against the German Empire and eventually negotiated terms to pull out of World War I. They then went to war against the White movement, pro-independence movements, rebellious peasants, former supporters, anarchists and foreign interventionists in the bitter civil war. They set up the Soviet Union in 1922 with Vladimir Lenin in charge. At first, it was treated as an unrecognized pariah state because of its repudiating of tsarist debts and threats to destroy capitalism at home and around the world. By 1922, Moscow had repudiated the goal of world revolution, and sought diplomatic recognition and friendly trade relations with the capitalist world, starting with Britain and Germany. Finally, in 1933, the United States gave recognition. Trade and technical help from Germany and the United States arrived in the late 1920s. After Lenin died in 1924, Joseph Stalin, became leader. He transformed the country in the 1930s into an industrial and military power. It strongly opposed Nazi Germany until August 1939, when it suddenly came to friendly terms with Berlin in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. Moscow and Berlin by agreement invaded and partitioned Poland and the Baltic States. Stalin ignored repeated warnings that Hitler planned to invade. He was caught by surprise in June 1941 when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. The Soviet forces nearly collapsed as the Germans reached the outskirts of Leningrad and Moscow. However, the Soviet Union proved strong enough to defeat Nazi Germany, with help from its key World War II allies, Britain and the United States. The Soviet army occupied most of Eastern Europe and increasingly controlled the governments.

The Hashemite Arab Federation was a short-lived confederation that lasted from 14 February to 2 August 1958, between the Hashemite kingdoms of Iraq and Jordan. Although the name implies a federal structure, it was de facto a confederation.

United States foreign policy in the Middle East has its roots in the early 19th-century Tripolitan War that occurred shortly after the 1776 establishment of the United States as an independent sovereign state, but became much more expansive in the aftermath of World War II. With the goal of preventing the Soviet Union from gaining influence in the region during the Cold War, American foreign policy saw the deliverance of extensive support in various forms to anti-communist and anti-Soviet regimes; among the top priorities for the U.S. with regards to this goal was its support for the State of Israel against its Soviet-backed neighbouring Arab countries during the peak of the Arab–Israeli conflict. The U.S. also came to replace the United Kingdom as the main security patron for Saudi Arabia as well as the other Arab states of the Persian Gulf in the 1960s and 1970s in order to ensure, among other goals, a stable flow of oil from the Persian Gulf. As of 2023, the U.S. has diplomatic relations with every country in the Middle East except for Iran, with whom relations were severed after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, and Syria, with whom relations were suspended in 2012 following the outbreak of the Syrian Civil War.

The 'OMEGA' Memorandum of March 28, 1956, was a secret U.S. informal policy memorandum drafted by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles for President Dwight D. Eisenhower. The goal of the policy was to reduce the influence in the Middle East of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser because he seemed to be leaning in favor of the Soviet Union and he failed to provide the leadership that Dulles and Eisenhower had desired toward settling the Arab-Israeli conflict. Eisenhower approved the memorandum. Around the same time, the |British government formulated a similar strategy. The United States and the United Kingdom intended to coordinate activities between them to implement the new strategies in successive stages.

The 14 July Revolution, also known as the 1958 Iraqi military coup, was a coup d'état that took place on 14 July 1958 in Iraq, resulting in the toppling of King Faisal II and the overthrow of the Hashemite-led Kingdom of Iraq. The Iraqi Republic established in its wake ended the Hashemite Arab Federation between Iraq and Jordan that had been established just six months earlier.

Central Intelligence Agency activities in Syria since the agency's inception in 1947 have included coup attempts and assassination plots, and in more recent years, extraordinary renditions, a paramilitary strike, and funding and military training of forces opposed to the current government.

The National Party was a Syrian political party founded in 1947, eventually dissolving in 1963, after the Syrian Ba'ath Party established one-party rule in Syria in a coup d'état. It grew out of the National Bloc, which opposed the Ottomans in Syria, and later demanded independence from the French mandate. The party saw the greatest support among the Damascene old guard and industrialists. It supported closer ties with the Arab countries and territories to Syria's south, mainly Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Lebanon, and Mandatory Palestine, although it began supporting Hashemite-ruled Iraq and Jordan starting in 1949 amongst growing public support. While the dominant party in 1940s and early 1950s, it was replaced by its rival, the People's Party, thereafter. Similar to the People's Party, the National Party was also supported by landowners and landlords.

The Arab Cold War was a political rivalry in the Arab world from the early 1950s to the late 1970s and a part of the wider Cold War. It is generally accepted that the beginning of the Arab Cold War is marked by the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, which led to Gamal Abdel Nasser becoming president of Egypt in 1956. Thereafter, newly formed Arab republics, inspired by revolutionary secular nationalism and Nasser's Egypt, engaged in political rivalries with conservative traditionalist Arab monarchies, influenced by Saudi Arabia. The Iranian Revolution of 1979, and the ascension of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini as leader of Iran, is widely seen as the end of this period of internal conflicts and rivalry. A new era of Arab-Iranian tensions followed, overshadowing the bitterness of intra-Arab strife.

The United States foreign policy during the presidency of John F. Kennedy from 1961 to 1963 included diplomatic and military initiatives in Western Europe, Southeast Asia, and Latin America, all conducted amid considerable Cold War tensions with the Soviet Union and its satellite states in Eastern Europe. Kennedy deployed a new generation of foreign policy experts, dubbed "the best and the brightest". In his inaugural address Kennedy encapsulated his Cold War stance: "Let us never negotiate out of fear. But let us never fear to negotiate".

Afif al-Bizri was a Syrian career military officer who served as the chief of staff of the Syrian Army between 1957–1959. He was known for his communist sympathies, and for spearheading the union movement between Syria and Egypt in 1958.

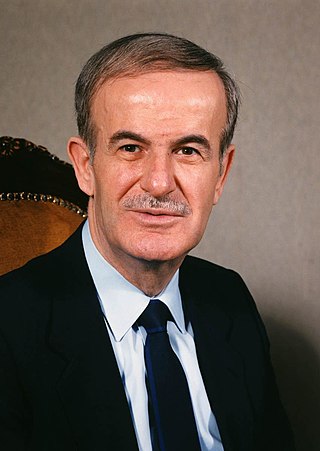

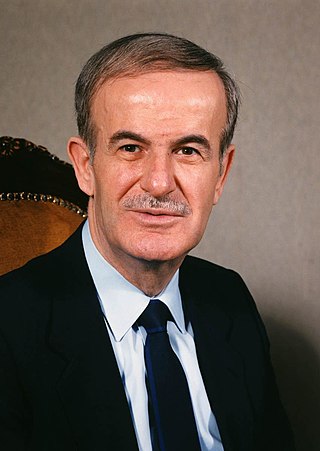

Hafez al-Assad served as the President of Syria from 12 March 1971 until his death on 10 June 2000. He had been Prime Minister of Syria, leading a government for two years. He was succeeded by his son, Bashar al-Assad.

Ali Abu Nuwar was a Jordanian military officer who served as chief of staff of the Jordanian Armed Forces from May 1956 to April 1957. He participated in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War as an artillery officer in the Jordanian army's predecessor, the Arab Legion, but his vocal opposition to British influence in Jordan led to his virtual exile to Paris as military attaché in 1952. There, he forged close ties with Jordanian crown prince Hussein, who promoted Abu Nuwar after his accession to the throne.

The United States foreign policy of the Dwight D. Eisenhower administration, from 1953 to 1961, focused on the Cold War with the Soviet Union and its satellites. The United States built up a stockpile of nuclear weapons and nuclear delivery systems to deter military threats and save money while cutting back on expensive Army combat units. A major uprising broke out in Hungary in 1956; the Eisenhower administration did not become directly involved, but condemned the military invasion by the Soviet Union. Eisenhower sought to reach a nuclear test ban treaty with the Soviet Union, but following the 1960 U-2 incident the Kremlin canceled a scheduled summit in Paris.