The Dardanelles, also known as the Strait of Gallipoli and in Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont, is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey that forms part of the continental boundary between Asia and Europe and separates Asian Turkey from European Turkey. Together with the Bosporus, the Dardanelles forms the Turkish Straits.

The (Montreux) Convention regarding the Regime of the Straits, often known simply as the Montreux Convention, is an international agreement governing the Bosporus and Dardanelles Straits in Turkey. Signed on 20 July 1936 at the Montreux Palace in Switzerland, it went into effect on 9 November 1936, addressing the long running Straits Question over who should control the strategically vital link between the Black and Mediterranean seas.

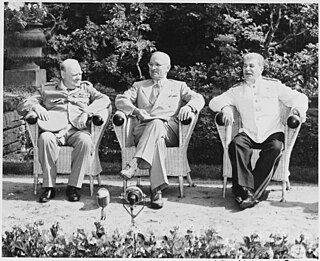

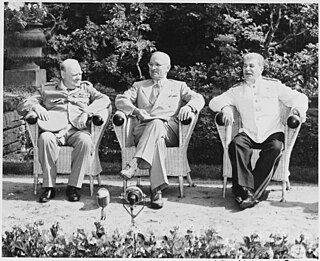

The Potsdam Conference was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. The participants were the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. They were represented respectively by General Secretary Joseph Stalin, Prime Ministers Winston Churchill and Clement Attlee, and President Harry S. Truman. They gathered to decide how to administer Germany, which had agreed to an unconditional surrender nine weeks earlier. The goals of the conference also included establishing the postwar order, solving issues on the peace treaty, and countering the effects of the war.

The Tehran Conference was a strategy meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943, after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. It was held at the Soviet Union's embassy at Tehran in Iran. It was the first of the World War II conferences of the "Big Three" Allied leaders and closely followed the Cairo Conference, which had taken place on 22–26 November 1943, and preceded the 1945 Yalta and Potsdam conferences. Although the three leaders arrived with differing objectives, the main outcome of the Tehran Conference was the Western Allies' commitment to open a second front against Nazi Germany. The conference also addressed the 'Big Three' Allies' relations with Turkey and Iran, operations in Yugoslavia and against Japan, and the envisaged postwar settlement. A separate contract signed at the conference pledged the Big Three to recognize Iranian independence.

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov was a Russian and later Soviet politician and diplomat, an Old Bolshevik, and a leading figure in the Soviet government from the 1920s onward. He served as Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars from 1930 to 1941 and as Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1939 to 1949 and from 1953 to 1956.

The Austrian State Treaty or Austrian Independence Treaty re-established Austria as a sovereign state. It was signed on 15 May 1955 in Vienna, at the Schloss Belvedere among the Allied occupying powers and the Austrian government. The neighbouring Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia acceded to the treaty subsequently. It officially came into force on 27 July 1955.

In the London Straits Convention concluded on 13 July 1841 between the Great Powers of Europe at the time—Russia, the United Kingdom, France, Austria and Prussia—the "ancient rule" of the Ottoman Empire was re-established by closing the Turkish Straits, which link the Black Sea to the Mediterranean, from all warships whatsoever, barring those of the Sultan's allies during wartime. It thus benefited British naval power at the expense of Russia as the latter lacked direct access for its navy to the Mediterranean.

After the Russian Revolution, in which the Bolsheviks took over parts of the collapsing Russian Empire in 1918, they faced enormous odds against the German Empire and eventually negotiated terms to pull out of World War I. They then went to war against the White movement, pro-independence movements, rebellious peasants, former supporters, anarchists and foreign interventionists in the bitter civil war. They set up the Soviet Union in 1922 with Vladimir Lenin in charge. At first, it was treated as an unrecognized pariah state because of its repudiating of tsarist debts and threats to destroy capitalism at home and around the world. By 1922, Moscow had repudiated the goal of world revolution, and sought diplomatic recognition and friendly trade relations with the capitalist world, starting with Britain and Germany. Finally, in 1933, the United States gave recognition. Trade and technical help from Germany and the United States arrived in the late 1920s. After Lenin died in 1924, Joseph Stalin, became leader. He transformed the country in the 1930s into an industrial and military power. It strongly opposed Nazi Germany until August 1939, when it suddenly came to friendly terms with Berlin in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. Moscow and Berlin by agreement invaded and partitioned Poland and the Baltic States. Stalin ignored repeated warnings that Hitler planned to invade. He was caught by surprise in June 1941 when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. The Soviet forces nearly collapsed as the Germans reached the outskirts of Leningrad and Moscow. However, the Soviet Union proved strong enough to defeat Nazi Germany, with help from its key World War II allies, Britain and the United States. The Soviet army occupied most of Eastern Europe and increasingly controlled the governments.

The Tito–Stalin split or the Soviet–Yugoslav split was the culmination of a conflict between the political leaderships of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, under Josip Broz Tito and Joseph Stalin, respectively, in the years following World War II. Although presented by both sides as an ideological dispute, the conflict was as much the product of a geopolitical struggle in the Balkans that also involved Albania, Bulgaria, and the communist insurgency in Greece, which Tito's Yugoslavia supported and the Soviet Union secretly opposed.

The Turkish Straits are two internationally significant waterways in northwestern Turkey. The Straits create a series of international passages that connect the Aegean and Mediterranean seas to the Black Sea. They consist of the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus. The straits are on opposite ends of the Sea of Marmara. The straits and the Sea of Marmara are part of the sovereign sea territory of Turkey and subject to the regime of internal waters.

The percentages agreement was a secret informal agreement between British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin during the Fourth Moscow Conference in October 1944. It gave the percentage division of control over Eastern European countries, dividing them into spheres of influence. It is also known as the naughty document, a nickname coined by Churchill himself due to his concerns regarding American reaction to any deal with such strong imperialist undertones, although in reality U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt was consulted tentatively and conceded to the agreement. The content of the agreement was first made public by Churchill in 1953 in the final volume of his memoir. The US ambassador Averell Harriman, who was supposed to represent Roosevelt in these meetings, was excluded from this discussion.

Russia–Turkey relations are the bilateral relations between Russia and Turkey and their antecedent states. Relations between the two are rather cyclical. From the late 16th until the early 20th centuries, relations between the Ottoman and Russian empires were normally adverse and hostile and the two powers were engaged in numerous Russo-Turkish wars, including one of the longest wars in modern history. Russia attempted to extend its influence in the Balkans and gain control of the Bosphorus at the expense of the weakening Ottoman Empire. As a result, the diplomatic history between the two powers was extremely bitter and acrimonious up to World War I. However, in the early 1920s, as a result of the Bolshevik Russian government's assistance to Turkish revolutionaries during the Turkish War of Independence, the governments' relations warmed. Relations again turned sour at the end of WWII as the Soviet government laid territorial claims and demanded other concessions from Turkey. Turkey joined NATO in 1952 and placed itself within the Western alliance against the Warsaw Pact during the Cold War, when relations between the two countries were at their lowest level. Relations began to improve the following year, when the Soviet Union renounced its territorial claims after the death of Stalin.

German–Soviet Axis talks occurred in October and November 1940 concerning the Soviet Union's potential adherent as a fourth Axis power during World War II. The negotiations, which occurred during the era of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, included a two-day conference in Berlin between Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov and Adolf Hitler and German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop. The talks were followed by both countries trading written proposed agreements.

Jamil Hasanli is an Azerbaijani historian, author and politician. He served as a professor at Baku State University in 1993–2011 and as a professor at Khazar University in 2011–2013. He was an advisor to the President of Azerbaijan in 1993 and served two terms in the Parliament of Azerbaijan between 2000 and 2010. He was the main opposition candidate in the 2013 Azerbaijani presidential election where he came in second with 5.53% of votes. He has been the leader of National Council of Democratic Forces of Azerbaijan since 2013.

According to the memories of Nikita Khrushchev, the deputy premier Lavrentiy Beria (1946–1953) pressed Joseph Stalin to claim eastern Anatolian territory that had supposedly been stolen from Georgia by the Turks. For practical reasons, the Soviet claims, if successful, would have strengthened the state's position around the Black Sea and would weaken British influence in the Middle East.

Soviet Union–Turkey relations were the diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union and the Republic of Turkey.

The deportation of the Meskhetian Turks was the forced transfer by the Soviet government of the entire Meskhetian Turk population from the Meskheti region of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic to Central Asia on 14 November 1944. During the deportation, between 92,307 and 94,955 Meskhetian Turks were forcibly removed from 212 villages. They were packed into cattle wagons and mostly sent to the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic. Members of other ethnic groups were also deported during the operation, including Kurds and Hemshins, bringing the total to approximately 115,000 evicted people. They were placed in special settlements where they were assigned to forced labor. The deportation and harsh conditions in exile caused between 12,589 to 50,000 deaths.

Soviet involvement in regime change entailed both overt and covert actions aimed at altering, replacing, or preserving foreign governments. In the 1920s, the nascent Soviet Union intervened in multiple governments primarily in Asia, acquiring the territory of Tuva and making Mongolia into a satellite state. During World War II, the Soviet Union helped overthrow many puppet regimes of Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan, including in East Asia and much of Europe. Soviet forces were also instrumental in ending the rule of Adolf Hitler over Germany.

Deportation of Azerbaijanis from Armenia – is the resettlement of the Azerbaijani population of the Armenian SSR in 1947-1950, which was carried out in accordance with the Decree of the Council of Ministers of the USSR No. 4083 dated with 23 December 1947.

The Cold War from 1947 to 1948 is the period within the Cold War from the Truman Doctrine in 1947 to the incapacitation of the Allied Control Council in 1948. The Cold War emerged in Europe a few years after the successful US–USSR–UK coalition won World War II in Europe, and extended to 1989–1991. It took place worldwide, but it had a partially different timing outside Europe. Some conflicts between the West and the USSR appeared earlier. In 1945–1946 the US and UK strongly protested Soviet political takeover efforts in Eastern Europe and Iran, while the hunt for Soviet spies made the tensions more visible. However, historians emphasize the decisive break between the US–UK and the USSR came in 1947–1948 over such issues as the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan and the breakdown of cooperation in governing occupied Germany by the Allied Control Council. In 1947, Bernard Baruch, the multimillionaire financier and adviser to presidents from Woodrow Wilson to Harry S. Truman, coined the term "Cold War" to describe the increasingly chilly relations between three World War II Allies: the United States and British Empire together with the Soviet Union.