Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony in 1926 and thereafter was regarded as a major composer.

Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev was a Russian composer, pianist, and conductor who later worked in the Soviet Union. As the creator of acknowledged masterpieces across numerous music genres, he is regarded as one of the major composers of the 20th century. His works include such widely heard pieces as the March from The Love for Three Oranges, the suite Lieutenant Kijé, the ballet Romeo and Juliet—from which "Dance of the Knights" is taken—and Peter and the Wolf. Of the established forms and genres in which he worked, he created—excluding juvenilia—seven completed operas, seven symphonies, eight ballets, five piano concertos, two violin concertos, a cello concerto, a symphony-concerto for cello and orchestra, and nine completed piano sonatas.

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky was a Russian composer and conductor with French citizenship and American citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the 20th century and a pivotal figure in modernist music.

Aaron Copland was an American composer, critic, writer, teacher, pianist, and conductor of his own and other American music. Copland was referred to by his peers and critics as the "Dean of American Composers". The open, slowly changing harmonies in much of his music are typical of what many consider the sound of American music, evoking the vast American landscape and pioneer spirit. He is best known for the works he wrote in the 1930s and 1940s in a deliberately accessible style often referred to as "populist" and which he called his "vernacular" style. Works in this vein include the ballets Appalachian Spring, Billy the Kid and Rodeo, his Fanfare for the Common Man and Third Symphony. In addition to his ballets and orchestral works, he produced music in many other genres, including chamber music, vocal works, opera, and film scores.

Roy Ellsworth Harris was an American composer. He wrote music on American subjects, and is best known for his Symphony No. 3.

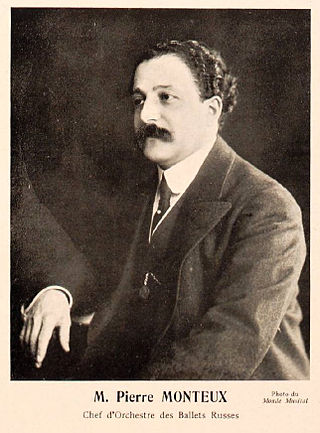

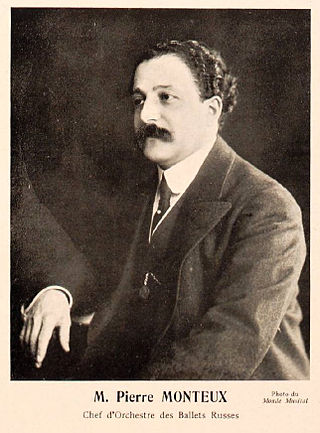

Pierre Benjamin Monteux was a French conductor. After violin and viola studies, and a decade as an orchestral player and occasional conductor, he began to receive regular conducting engagements in 1907. He came to prominence when, for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes company between 1911 and 1914, he conducted the world premieres of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring and other prominent works including Petrushka, The Nightingale, Ravel's Daphnis et Chloé, and Debussy's Jeux. Thereafter he directed orchestras around the world for more than half a century.

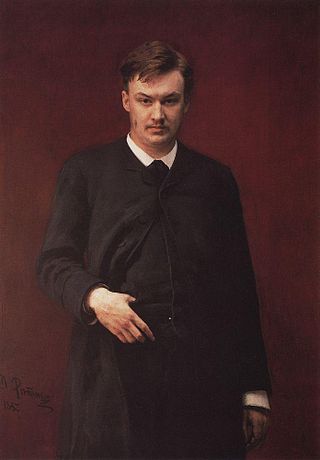

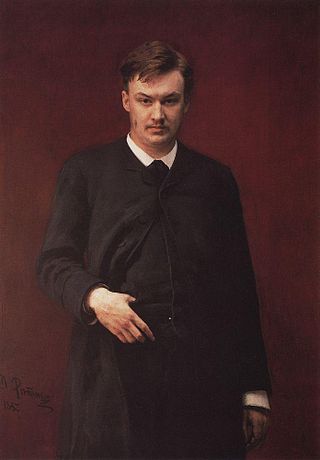

Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov was a Russian composer, music teacher, and conductor of the late Russian Romantic period. He was director of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory between 1905 and 1928 and was instrumental in the reorganization of the institute into the Petrograd Conservatory, then the Leningrad Conservatory, following the Bolshevik Revolution. He continued as head of the Conservatory until 1930, though he had left the Soviet Union in 1928 and did not return. The best-known student under his tenure during the early Soviet years was Dmitri Shostakovich.

Alexander Tansman was a Polish composer, pianist and conductor who became a naturalized French citizen in 1938. One of the earliest representatives of neoclassicism, associated with École de Paris, Tansman was a globally recognized and celebrated composer.

Boris Vladimirovich Asafyev was a Russian and Soviet composer, writer, musicologist, musical critic and one of founders of Soviet musicology. He is the dedicatee of Prokofiev's First Symphony. He was born in Saint Petersburg.

The Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF) was an anti-communist cultural organization founded on 26 June 1950 in West Berlin. At its height, the CCF was active in thirty-five countries. In 1966 it was revealed that the Central Intelligence Agency was instrumental in the establishment and funding of the group. The congress aimed to enlist intellectuals and opinion makers in a war of ideas against communism.

Cultural diplomacy is a type of soft power that includes the "exchange of ideas, information, art, language and other aspects of culture among nations and their peoples in order to foster mutual understanding". The purpose of cultural diplomacy is for the people of a foreign nation to develop an understanding of the nation's ideals and institutions in an effort to build broad support for economic and political objectives. In essence "cultural diplomacy reveals the soul of a nation", which in turn creates influence. Public diplomacy has played an important role in advancing national security objectives.

Loris Haykasi Tjeknavorian is an Iranian Armenian composer and conductor. He has appeared internationally as a conductor, serving as the principal conductor of the Armenian Philharmonic Orchestra from 1989 to 1998 and later from 1999 to 2000. As a composer Tjeknavorian has written 6 operas, 5 symphonies, choral works, chamber music, ballet music, piano and vocal works, concerti for piano, violin, guitar, cello and pipa, as well as music for documentary and feature films. Among his best known works are the opera Rostam and Sohrab, based on the story of Rostam and Sohrab from Ferdowsi's Shahnameh, and the ballet Simorgh.

The Wedding, or Svadebka (Russian: Свадебка), is a Russian-language ballet-cantata by Igor Stravinsky scored unusually for four vocal soloists, chorus, percussion and four pianos. Dedicating the work to impresario Sergei Diaghilev, the composer described it in French as "choreographed Russian scenes with singing and music" [sic], and it remains known by its French name of Les noces despite being Russian.

Maximilian Osseyevich Steinberg was a Russian composer of classical music.

Nicolas Nabokov was a Russian-born composer, writer, and cultural figure. He became a U.S. citizen in 1939.

The Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra is a major orchestra of Israel. Since the 1980s, the JSO has been based in the Henry Crown Symphony Hall, part of the Jerusalem Theater complex.

Joseph Horowitz is an American cultural historian who writes mainly about the institutional history of classical music in the United States. As a concert producer, he promotes thematic programming and new concert formats. His tenure as artistic advisor and subsequently executive director of the Brooklyn Philharmonic at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (1992–1997) attracted national attention for its radical departure from tradition. He is the host of the "More than Music" radio series on 1A, distributed by NPR.

The Virginia Arts Festival is a Norfolk-based non-profit arts presenter which serves southeastern Virginia, offering dozens of performances during the spring and throughout the year. Virginia Arts Festival performances have included international ballet companies, along with modern, contemporary, and ethnic dance companies; world-renowned soloists and ensembles in musical genres including classical, jazz, world, folk, rock, blues, bluegrass, country, and pop; opera; theater and cabaret; and collaborative productions with local arts organizations like the Virginia Symphony Orchestra.

The Committee for Cultural Freedom (CCF) was an American political organization active from 1939 to 1951 which advocated opposition to the totalitarianism of both the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany in foreign affairs, and promoted pro-democratic reforms in public and private institutions domestically. Co-founded by influential philosopher and educator John Dewey and the anti-Soviet Marxist academic Sidney Hook, it was reorganized in January 1951 into the American Committee for Cultural Freedom.

The Seventh Army Symphony Orchestra was the only symphonic orchestral ensemble ever created under the supervision of the United States Army. Founded by the composer Samuel Adler, its members participated in the cultural diplomacy initiatives of the United States in an effort to demonstrate the shared cultural heritage of the United States, its European allies and the vanquished countries of Europe during the post World War II era.